7. DGA-Nachwuchstagung „Umbruch und Entwicklung in Asien“

Vortrag von Nina Khan, 18. Januar 2015, Burg Rothenfels

Neue Geber, neue Diskurse? Entwicklungsdiskurse im Rahmen von Süd-Süd-Kooperationen am Beispiel Indien

Abstract:

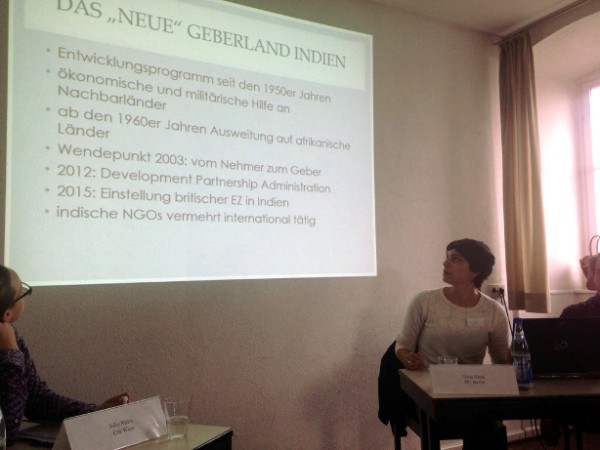

Das „neue“ Geberland Indien

Im Mittelpunkt meines Projekts steht der Neue Geber Indien, ein Land, das lange Zeit zu den größten Empfängern von „Entwicklungshilfe“ weltweit zählte[i]. Seit einigen Jahren tritt Indien nun vermehrt als Geberland in der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit (EZ) auf und hat den Erhalt von Entwicklungsgeldern drastisch reduziert. Obwohl als Neuer Geber gehandelt, reichen Indiens Geberaktivitäten bereits bis in die 1950er Jahre zurück. Zunächst im Rahmen ökonomischer und militärischer Hilfe auf Nachbarländer gerichtet, weiteten sich diese ab den 1960er Jahren auf afrikanische Länder aus. Dennoch verschob sich erst mit dem 2003 eingeleiteten Wendepunkt in der staatlichen indischen EZ[ii] der Fokus von Indiens Nehmer- auf seinen Geberstatus, von Armut innerhalb Indiens auf seine Rolle als aufstrebende Wirtschaft (Kragelund 2010). „To brand India anew“ (Kragelund 2010, 3) war ein Ziel dieses Wandels, der im Kontext der wirtschaftlichen Liberalisierung Indiens in den 1990er Jahren und seiner wachsenden politischen Bedeutung auf internationaler Ebene zu sehen ist (Jobelius 2007; Hoepf Young 2008)[iii].

Die Neuen Geber

Indiens Erstarken als Geberland ist eingebettet in den größeren Kontext des Wandels in der globalen Entwicklungshilfearchitektur, der durch das vermehrte Engagement der sogenannten Neuen Geber (u.a. China, Brasilien, Südafrika und Venezuela) im Rahmen von Süd-Süd-Kooperationen gekennzeichnet ist. Bei den unter diesem Begriff subsumierten, höchst diversen Gebern handelt es sich um Länder, die teilweise selbst (ehemalige) Empfänger sowie ehemals kolonisiert sind und sich nicht den Normen und Standards des „westlich“[iv] dominierten OECD-Entwicklungshilfeausschusses DAC (Development Assistance Committee)[v] verpflichtet haben. Die oftmals generalisierenden Charakterisierungen der Neuen Geber nennen die ausdrückliche Verknüpfung ihrer EZ mit wirtschaftlichen Eigeninteressen, die Ausrichtung auf sogenannte win-win-Ergebnisse, die Fokussierung auf Infrastrukturprojekte und die Abwesenheit politischer Konditionalität (Klingebiel 2013, 23). Während die Nehmerländer dies oftmals begrüßen, stellt dies eine Hauptangriffsfläche für Kritik dar und wird als in Opposition zu den DAC-Normen und Standards stehend gesehen.

Das Erstarken der Neuen Geber ist nicht nur im Hinblick auf zukünftige steigende Entwicklungsetats, sondern insbesondere in Bezug auf einen „Neuentwurf“ der EZ insgesamt relevant, welcher neben der Praxis auch die normative Ausrichtung betrifft. Diese normative Dimension ist das zentrale Thema meiner Dissertation, in der ich den staatlichen indischen Entwicklungsdiskurs untersuchen möchte.

Wenngleich kein mit dem DAC vergleichbares Gremium der Neuen Geber zur Standardisierung und Förderung der Wirksamkeit von EZ existiert[vi], so lassen sich laut Mawdsely (2011) grundlegende Gemeinsamkeiten in ihrer normativen Ausrichtung feststellen. Hierzu zählen die Beteuerung einer geteilten Erfahrung kolonialer Ausbeutung, postkolonialer Ungleichheit und der daraus entstandenen Identität als „Entwicklungsland“, eine spezifische Expertise in angemessenen Entwicklungsansätzen, die Ablehnung hierarchischer Geber-Nehmer-Beziehungen und Betonung von Respekt, Souveränität und Nicht-Einmischung sowie das Bestehen auf gegenseitigen Nutzen (Mawdsley 2011, 256, 263).

Die Neuen Geber stellen also nicht nur etablierte Arbeitsweisen der traditionellen Geber infrage sondern fordern ihre Dominanz auch durch eine offen kommunizierte Abweichung vom dominanten westlichen Entwicklungsdiskurs als Ganzem heraus.

Entwicklungsdiskurse und Machthierarchien in der EZ

Bevor ich nun exemplarisch auf die Entwicklungsdiskurse des Neuen Gebers Indien zu sprechen komme, möchte ich kurz auf die Grundannahmen meiner Arbeite eingehen. Ich gehe davon aus, dass die traditionellen Nord-Süd-Beziehungen der EZ von überwiegend asymmetrischen, rassifizierten Machtbeziehungen gekennzeichnet sind, die durch Entwicklungsdiskurse gestützt werden und wiederum ihren Ausdruck darin finden. Entwicklungsdiskurse spielen also in der Konstitution der Praxis der EZ eine entscheidende Rolle – sie besitzen jenseits einer rein linguistischen auch eine operative Dimension. Diskurse können Machthierarchien stützen, aber diskursive Verschiebungen können auch die soziale Praxis verändern.

Der „westliche“ Entwicklungsdiskurs gründet – trotz Veränderungen im Laufe der Geschichte der EZ – auf der Denkstruktur des Kolonialdiskurses, auf der „Zweiteilung der Welt in einen fortgeschrittenen, überlegenen Teil und einen zurückgebliebenen, minderwertigen Teil. Das Eigene dient als Norm, anhand derer die Minderwertigkeit des Fremden objektiv nachgewiesen wird.“ (Ziai 2004). Forschungen zur Nord-Süd-EZ haben zudem die stereotype und rassifizierte Darstellung von Zielgruppen aufgezeigt (u.a. Goudge 2003; Eriksson Baaz 2005), die sich aus dem Entwicklungsdiskurs speist. Dies verstehe ich als diskursive Wissensproduktion über Entwicklung, welche die Geber in eine Machtposition versetzt, indem sie autoritative Sprecherpositionen einnehmen.

In Bezug auf Indien, das ehemals kolonisiert sowie lange Zeit ein bedeutendes Empfängerland war, stellt sich die Frage, wie es als Geber Entwicklung definiert und inwiefern damit zusammenhängende Hierarchien fortbestehen, aufgeweicht werden oder abwesend sind. Weiterführend und vor dem Hintergrund des Zusammenhangs von Diskursen und sozialer Praxis, stellt sich dann die Frage nach der Bedeutung einer Pluralisierung von Entwicklungsdiskursen für die Machtbeziehungen in der EZ.

Entwicklungsdiskurse des Neuen Gebers Indien

Während das Empfängerland Indien dementsprechend als unterentwickelt und rückständig konstruiert wird, ist seine Gebermentalität geprägt von ebendiesen Erfahrungen als Nehmer und ehemalige Kolonie. Vor dem Hintergrund dieser historischen Verortung kann es nicht die westliche Entwicklungsrhetorik zur Legitimation gebrauchen (Six 2009, 1109). Die bereits genannten, stark verallgemeinerten Merkmale der Süd-Süd-EZ, lassen sich in der von Indien geführte Kommunikation über Entwicklung wiederfinden. Auch Indien bettet seine EZ in eine starke Rhetorik des Respekts für die Souveränität anderer Regierungen (Woods 2008, 13) und vermeidet bewusst die hierarchische, neo-imperialistischen Mentalität westlicher Geber (Mawdsley 2011). Hauptmerkmale indischer Entwicklungsaktivitäten sind Nicht-Einmischung, gegenseitiger Respekt für Souveränität, gegenseitiger Nutzen und Gleichheit (Katti, Chahoud, and Kaushik 2009). Diese Prinzipien der indischen Außen- und Entwicklungspolitik sind geprägt von den 1955 auf der Bandung-Konferenz formulierten Grundsätze der Blockfreien Staaten und geben dem Entwicklungsdiskurs damit eine historische Dimension. Diese fehlt den Post-Development-Vertreter_innen zufolge dem dominanten, westlich geprägten Entwicklungsdiskurs (Six 2009, 1107).

Drei Beispiele geben einen Einblick in die staatliche indische Entwicklungsrhetorik:

In der Rubrik „Development Partnerships“ der Zeitschrift India Perspectives des Indischen Außenministeriums wurde in einem Artikel anlässlich des zweiten Africa-India Summit 2011 gegenseitiger Nutzen und Reziprozität als Bestandteil indischer EZ in Afrika offen benannt. Im Gegenzug zu den von Indien angekündigten capacity-building Initiativen auf dem afrikanischen Kontinent im Wert von US$ 5,7 Milliarden versicherte die Afrikanische Union die Unterstützung Indiens in seiner UN Politik:

“The African Union reciprocated by telling India that it can ‚count on its support‘ for the UN reforms. It also declared support for New Delhi’s claim for a permanent seat in the UN Security Council.“ (Chand 2011, 18)

Mawdsley verdeutlicht die Implikationen dieser kommunizierten Reziprozität aus dem Blickwinkel der gift theory[vii] in Anlehnung an Marcel Mauss (2000). Indem Indien den eigenen Nutzen seiner EZ offen benennt betont es die Fähigkeit des Empfängers zur Reziprozität und erhöht somit dessen Status. So entsteht eine gleichberechtigte soziale Beziehung im Gegensatz zur Minderwertigkeit, die die (vermeintlich) nicht vergoltene westliche Hilfe auf Dauer erzeugt (Mawdsley 2011, 264).

Weiterhin grenzt sich Indien explizit von der traditionellen Nord-Süd-EZ ab:

„We do not like to call ourselves a donor. We call it development partnership because it is in the framework of sharing development experiences. It follows a model different from that followed in the conventional North-South economic cooperation patterns (…).“ (Syed Akbaruddin, Joint Secretary des MEA anlässlich der Gründung der Development Partnership Administration 2012)

Doch nicht erst mit der Gründung der DPA im Jahr 2012 und im Zusammenhang mit dem Erstarken des Gebers Indien ist eine von Partnerschaft und gegenseitigen Nutzen geprägte Rhetorik zu verzeichnen. Bereits bei der Gründung des ITEC-Programms im Jahr 1964 lassen sich diese Themen in einem Statement des Indischen Kabinetts wiederfinden:

„(…) a programme of technical and economic cooperation is essential for the development of our relations with other developing countries on the basis of partnership and mutual benefit.“ (Ministry of External Affairs 2014)

Fazit

Indiens Empfänger werden (zumindest rhetorisch) als Entwicklungspartner behandelt, die auf der Basis gleichberechtigter Partnerschaft und gegenseitigen Nutzens solidarisch unterstützt werden. Ungeachtet der Machtbeziehungen in der Praxis der indischen Süd-Süd-EZ lässt sich daran ein vom dominanten westlichen abweichender Entwicklungsdiskurs erkennen.

Ausgehend von der Annahme, dass die konstatierten Machthierarchien in der traditionellen Nord-Süd-EZ in entscheidendem Maße von Entwicklungsdiskursen getragen werden und diese perpetuieren, birgt ein egalitär ausgerichteter Diskurs die Chance, diese Hierarchien zu verändern.

Umso relevanter ist die Untersuchung der normativen Dimension indischer EZ, die den bisherigen Fokus auf politische und ökonomische Aspekte erweitert. Es bleibt zudem zu untersuchen, inwiefern sich ein gleichberechtigter Entwicklungsdiskurs auch in der Praxis indischer EZ niederschlägt.

Endnoten

[i] Ende der 1960er Jahre erhielt Indien ca. US$ 5,5 Mrd. Entwicklungshilfe jährlich (Kragelund 2011, 590).

[ii] Der damalige Finanzminister Singh beschränkte den Erhalt bilateraler Hilfe auf fünf Staaten, kündigte vermehrte Unterstützung für sogenannte „Entwicklungsländer“, Schuldenerlass sowie die gesamte Rückzahlung der eigenen Schulden an.

[iii] Der forcierte Imagewandel vom krisengeschüttelten „Entwicklungsland“ hin zur ökonomisch und politisch aufstrebenden Macht wurde mit der 2004 ins Leben gerufenen „Brand India“-Kampagne weiterverfolgt (Schneider 2011).

[iv] Die Verwendung bestimmter Begrifflichkeiten, wie z.B. Nord/Süd, westlich/nicht-westlich, Neue und Traditionelle Geber weist einige Fallstricke auf, die jedoch aufgrund des begrenzten Umfangs dieses Vortrags nicht ausführlich erörtert werden können. Es sei an dieser Stelle nur auf den binären Konstruktionscharakter dieser Terminologie und die damit verbundenen Wertungen sowie das Problem der Verallgemeinerung verwiesen. Dennoch kann ich dem Gebrauch essentialisierender Begrifflichkeiten vorerst nicht entkommen, da genau diese Grundlage und Ausdruck bestehender und zu kritisierender Machthierarchien sind. „The available language is imperfect but, (…), it is reflective of existing power imbalances on a global scale, in both the discursive and material realms.“ (Goudge 2003, 46 Fn 2).

[v] Das DAC hat derzeit 29 Mitglieder und wird von europäischen Staaten sowie den USA dominiert. Ausnahmen bilden Japan (seit 1961 Mitglied) und Korea (seit 2010 Mitglied). http://www.oecd.org/dac/dacmembers.htm (Zugriff am 03.11.2014).

[vi] Zwar definierte die Gruppe der G77 im Yamoussoukro Consensus von 2008 grundlegende Prinzipien der Süd-Süd-Kooperation (Gleichheit, Solidarität, gegenseitige Entwicklung und Ergänzung), doch gehen damit anders als beim DAC nicht gemeinsamen Standards für Monitoring und Evaluierung einher (Morazán and Müller 2014, 15, 26; http://www.g77.org/ifcc12/Yamoussoukro_Consensus.pdf (Zugriff am 01.07.2013)).

[vii] Die gift theory wurde bereits mehrfach in der Untersuchung der Nord-Süd-EZ angewandt, u.a. im Hinblick auf Machtbeziehungen (Mawdsley 2011, 256; Mawdsley and McCann 2011, 169).

Literatur

Chand, Manish. „Enduring Partnerships“. India Perspectives, August 2011, 18–23.

Eriksson Baaz, Maria. The paternalism of partnership: a postcolonial reading of identity in development aid. London: Zed Books, 2005.

G 77. „Yamoussoukro Consensus on South South Cooperation“, 2008. http://www.g77.org/ifcc12/Yamoussoukro_Consensus.pdf.

Goudge, Paulette. The Whiteness of Power: Racism in Third World Development and Aid. London: Lawrence & Wishart Ltd, 2003.

Hoepf Young, Malea. “ New” Donors: A New Resource for Family Planning and Reproductive Health Financing?. Research Commentary. Population Action International, August 2008.

Jobelius, Matthias. New Powers for Global Change? Challenges for the International Development Cooperation. The Case of India. FES Briefing Paper 5, FES Berlin., März 2007.

Katti, Vijaya, Tatjana Chahoud, und Atul Kaushik. India’s Development Cooperation – Opportunities and Challenges for International Development Cooperation. Briefing Paper. Deutsches Institut für Entwicklung, März 2009.

Klingebiel, Stephan. Entwicklungszusammenarbeit: eine Einführung: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik. Studies. Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2013.

Kragelund, Peter. „Back to BASICs? The Rejuvenation of Non-Traditional Donors’ Development Cooperation with Africa“. Development and Change 42, Nr. 2 (1. März 2011): 585–607.

———. „India’s African Engagement“. Real Instituto Elcano, Nr. ARI 10/2010 (2010).

Mauss, Marcel. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Übersetzt von W. D. Halls. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Mawdsley, Emma. „The Changing Geographies of Foreign Aid and Development Cooperation: Contributions from Gift Theory“. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37, Nr. 2 (2011): 256–72.

Mawdsley, Emma, und Gerard McCann, Hrsg. India in Africa: Changing Geographies of Power. Cape Town: Pambazuka Press, 2011.

Ministry of External Affairs. „50 Years of ITEC. Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation Programme.“, 2014.

Morazán, Pedro, und Franziska Müller. BRICS als neue Akteure der Entwicklungspolitik. Brasilien, Russland, Indien, China und Südafrika als Geber. SÜDWIND – Institut für Ökonomie und Ökumene, Mai 2014.

Schneider, Nadja-Christina. „Media Research beyond Bollywood, or: Some Thoughts on a Systematic Media Perspective in India-related Research“. Media and Social Identities in India – and beyond. Sonderausgabe der Zeitschrift: Internationales Asienforum/International Quarterly for Asian Studies 42, Nr. 3–4 (2011): 223–38.

Six, Clemens. „The Rise of Postcolonial States as Donors: A Challenge to the Development Paradigm?“. Third World Quarterly 30, Nr. 6 (2009): 1103–21.

Taneja, Kabir. „India Sets up Global Aid Agency“. The Sunday Guardian, 1. Juli 2012. http://www.sunday-guardian.com/news/india-sets-up-global-aid-agency.

Woods, Ngaire. „Whose Aid? Whose Influence? China, Emerging Donors and the Silent Revolution in Development Assistance“. International Affairs 84, Nr. 6 (2008): 1205–21.

Ziai, Aram. „Imperiale Repräsentationen Vom kolonialen zum Entwicklungsdiskurs“. sopos 4/2004, 2004.

Mette Gabler

Change/Media/Gender

Changes in Indian society post-liberalisation are signified by economic growth and thriving consumer cultures among financially-abled parts of the population. The onset of satellite TV and the increase of international investments have resulted in a complex expansion of media systems and thereby, an explosion of medialised messages and imageries. Increasingly visible are, for example, the growing number of private TV channels and the expansion of the commercial advertising industry and its campaigns, which despite the foreign presence, has since seen manifold examples of regionalisation in various parts of the media systems, e.g. the press and commercial advertising (Schneider, 2013, p. 2-3).

In these processes of a changing society, the dynamics of transformation contain opposing viewpoints, whose representatives debate the benefits or dangers of change. Promoters of change and opposing voices are intertwined through diverse faceted perspectives. Amongst the elements that feed this tug of war is gender. Particularly, the significance of media systems and content in regards to changing gender patterns, e.g. stereotypes, roles and expectations, are being discussed among academic studies, activists and institutions alike. Questions of representation are therefore central to the debate on perceived transformations of society. The questions of this essay are: in what way is gender representation debated, and what are the patterns of these debates? The following will show, that debates on representation are very one-sided and reproduce power relations that are situated in a binary understanding of gender and embedded in a heteronormative matrix. The present discourses highlight female representation and thereby limit the understanding of gender dynamics all in all.

Debates on Representations in Indian Media

According to sociologist Maitrayee Chaudhuri (2014), the context and historical development in India, i.e. new economic policies, the dynamics of the women’s movement and the prominence and outreach of media-cultures, have resulted in a hyper-visibility of gender in popular culture in particular (Chaudhuri, p. 145). In addition, news media have since the Nirbhaya case[1] increasingly covered sexualised violence and harassment as well as debated women’s safety and men’s involvement, exemplifying how debates on sexism and gender are increasingly present in mainstream media-cultures in the aftermath of this incident. At the same time, development initiatives, state-led as well as non-governmental, promote the incorporation of gender-mainstreaming in projects, focussing heavily on women’s empowerment, as well as addressing gender based violence and other issues concerning sexist practices, e.g. female foeticide or differing expectations according to sex. In many examples, social marketing campaigns are utilised to spread the messages. Thereby, the existing messages and imageries are a complex blend of commercial and social dynamics.

In academia, the representation of gender in media[2], e.g. in film, TV serials[3], print media and commercial advertising[4], has long been a popular field of study, particularly within the social sciences. These studies add to the existing imageries and debates on gender. Especially in connection with commercial advertising, Chaudhuri (2001) states in her study on gender representation in print advertising that “within modern advertising, gender is probably the social resource that is used most” (Chaudhuri, 2001, p. 375), arguing the prominent role gender plays among strategies of communicating with audiences.

The results of discussions of representation in popular culture, news media, academia etc. illustrate the various channels that debate the myriad of existing imageries. These studies and debates highlight the conviction in media’s influence and outline the importance regarding media content in particular as a salient part of socialisation processes.

The Women Centred Focus

A major point brought to light in the extensive material is that concerns around gender are heavily dominated by so-called women’s issues and the representation of women. Anthropologist Maila Stivens states that to activists in Asia in general ‚gender‘ often reads as ‚woman‘ (Stivens, 2006, p. 5). Papers discussing development communication in India support this claim by discussing how there is a need for protecting as well as actions towards empowering women (Vilanilam, 2009, p. 17; Sharma & Sharma, 2007). Although gender equality is the common term used in development initiatives, women are the focal point. Attempts of many initiatives to rectify inequalities focus on the multitude of atrocities committed against women and the discriminatory practises women face due to their sex (Uberoi, 1996, pp. xi–xii). This however results in an unbalanced mode of dealing with gender, victimisation of women, and not considering the complexities of gendered systems. A question to be asked is for example: How can a woman be empowered if her power is not recognised? Although the importance of the women’s movement in India can not be understated and a number of publications discuss this part of India’s history in the connection with particular media strategies use and visual media, i.e. social marketing[5], the focus in these also lies on particular women’s demand for equality and release from un-freedoms. However, in the greater scheme of gender equality the entire gendered system needs to be addressed.

That gender is often equated with women, also holds true for many academic studies, as illustrated by the publication by Dasgupta (2011) entitled “Media, Gender, and Popular Culture in India: Tracking Change and Continuity”. Despite intending to “critique the role of the media and its representation of popular culture and the position of Indian men and women in urban, suburban, and rural India” (Dasgupta, 2011, p. 4), debates on female representation predominate and male representation, apart from short examples of masculine representation, seems to function as a signifier of the gender gap.

Voices critical of the portrayal of gender imageries illustrate this point. The concerns regarding depictions of stereotypical gender roles in media and the discussion on representations that “celebrate the existing social order” (Chaudhuri, 2001, p. 375) i.e. depicting role models of normative behaviour and identities, especially focus on women‘ representation as housewives and/or care-takers. Commercial advertising in particular is noted to reinforce traditional power relations and patriarchal structures (Rao, 2001). Again substituting ‚gender‘ with ‚women‘. Within this context of commercial imageries being harmful to society, the depiction of women’s sexuality, nudity and bodies is common topic, once more turning the focus towards female representation. Feminists argue that this discussion exemplifies the constructions of femininity as a way of enforcing control over women’s lives (Munshi, 2001, p. 7).

These investigations surely are an important part of discourses on gender, and shed light on the ways stereotypes of women can be harmful as well as exemplifying patriarchal structures that subjugate the female part of a population. However, gendered dynamics are over-simplified by only focussing on this side of gender representation. Medialised messages can also be argued to challenge existing norms (Chaudhuri, 2001; Gabler, 2010). An investigation of female “avatars of homemaker” in commercial advertising in Indian print and television media by Shoma Munshi (1998) illustrates that “women’s spaces of resistance can be and are created by producers of media messages, even if that may not be their first intended aim” (Munshi, 1998, p. 574). This illustrates the complexity of debates circling women’s representation and is exemplified by various campaigns, be they with a social objective, a commercial goal, or potential overlaps. Campaigns might sell products, promote ideas of women’s empowerment or address public health considerations, but a single campaign can also be seen to sell a product through social causes or in connection with social messages, as for example the myriad campaigns utilising the international women’s day as a sales pitch for women centred products. Some commercial ads even seem to challenge existing social structures i.e. utilise society’s transformation for the purpose of product sales (Hero Honda’s slogan “why should boys have all the fun” plays on differing expectations of mobility according to sex). Similarly, social campaigns might utilise style and strategies of commercial marketing in order to promote social causes, e.g. “the ring the bell” campaign initiated by ‘breakthrough’ promoting individual intervention when suspecting domestic violence. Hence, media and gender are interlinked in various ways and open up perspectives of re-producing existing gender roles through images of the housewife and caretaker, who inherently is a woman, as well as offering potential to encourage gender equality.

Investigations on masculinities and male representation exist,[6] but are limited and their role in terms of participating in the quest for gender equality seems marginal. Instead of questioning masculinities in regard to sexualised violence, men’s role is often limited to that of a protector of women, in the end reproducing ideas of women as victims and in need of protection from evil-doers. This is exemplified by the Gillette razor campaign “Soldiers wanted […] to support the most important battle of the nation. To stand up for women. Because when you respect women… You respect your nation. Support the movement. Gillette salutes the soldier in you”. Apart from victimising the female population, this rhetoric also fastens the binary understanding of gender and its heteronormativity. Attempts to breach this trend are debates and studies in India that deal with Queer realities and representation in media.[7] According to Uberoi, focusing on masculinities “in the context of the Western ‚gay‘ movement’s challenge to conventional masculine role expectations” (Uberoi, 1996, p. xiii) has been the exception rather than the rule.

Beyond the Binary Heteronormativity

As shown, the logic of most studies follows ideas based upon the binary-system of gender, that follows heteronormative patterns of understanding. Within this system trans-realities and individuals born intersexual are overlooked and their realities treated as abnormalities. However, with as many as “up to one in every five hundred babies […] born ‚intersex‘ with chromosomes at odds with their anatomy” (Philips, 2001, p. 31 cited in Jolly, 2002, p. 10), the prevalence of people belonging and identifying with these communities can in no way be downplayed.

Additionally, the women centred focus limits the discourse, effectively ignoring gender dynamics, power relations and the practises that lead to discriminatory patterns. If sections of society are oppressed, subjugated, marginalised and discriminated against, then what makes this possible and in what ways are these patterns put into action and by whom? The oppression of the female sex does not exist on its own, it is a part of a gendered system, and is based on an understanding of how the world works through these gendered patterns and constructions. Discourses on gender cannot be limited to debates on femininity and women’s position in society as they are inextricably linked to notions of masculinity, the construction of binary sex-categories, and power relations within the gendered systems.

Gender is a complex category, but routinely simplified, especially in connection with advertising and other media representations. Debates concerning these representations reproduce the simplified present notions. I therefore argue for a more inclusive and fluid use and understanding of gender.

Notes:

[1] The Nirbhaya case describes the incidence of the gang rape of a 23 year old woman in Delhi in December 2012 that sparked demonstrations across India.

[2] Anthologies and other studies investigating the connections between gender and media include Bhavani & Vijayasree (2010), Chaudhuri (2014), Dasgupta (2011), Patowary (2014), Sardana (1984), and Yakkaldevi (2014).

[3] Studies on gender representation in TV-shows and film in India include Bachmann (2001), Cullity & Younger (2004), Fazal (2008), Ghosh (2001 + 2010), Khan (2011), Mankekar (1993), Munshi (2009), Muraleedharan (2001), Patel (2001), and Vasudevan (2000).

[4] Gender representations in commercial advertising in India are discussed by Chaudhuri (2001), Dutta (2013), Haynes (2012), Munshi (1998), Nigam & Jha (2007), Rajagopal (1999), Schaffter (2006), Sengupta (2014), Vanita (2001), and Wandrekar (2010).

[5] Examples include Kumar (1997), Murthy & Dasgupta (2011) and another Publication by Zubaan (2006).

[6] Haynes (2012) for example in his investigation of advertisements for sex tonics in western India from 1900–1945 discusses masculinity in regards to ideas of modernity at the time (Haynes, 2012).

[7] Some studies engage with lesbian relations e.g. Bachmann (2001) and Patel (2001), while others focus on male homosexual relations (Muraleedharan, 2001).

Bibliography:

Bachmann, M. (2001). After the Fire. In R. Vanita (Ed.), Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Bhavani, K. D., & Vijayasree, C. (Eds.). (2010). Woman as Spectator and Spectacle. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press India Pvt. Ltd.

Chaudhuri, M. (2001). Gender and advertisements: The rhetoric of globalisation. Women’s Studies International Forum, 24(3-4), 373–385.

Chaudhuri, M. (2014). Gender, Media and Popular Culture in a Global India. In L. Fernandes (Ed.), Routledge handbook of gender in South Asia (pp. 145–159). London ; New York: Routledge.

Cullity, J., & Younger, P. (2004). Sex Appeal and Cultural Liberty: A Feminist Inquiry into MTV India. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 25(2), 96–122.

Dasgupta, S. (2011). Media, Gender, and Popular Culture in India: Tracking Change and Continuity. New Delhi, India ; Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Dutta, S. (2013). Portrayal of Women in Indian Advertising: A Perspective. International Journal of Marketing and Technology, 3(3), 119–226.

Fazal, S. (2008). Emancipation or anchored individualism? Women and TV soaps in India. In M. Gokulsing (Ed.), Popular Culture in a Globalised India (1st ed., pp. 41–52). London: Routledge Chapman & Hall.

Gabler, M. (2010). The Good Life – Buy 1 Get 1 Free Messages of Outdoor Advertising for Social Change in Urban India. Retrieved from http://www.suedasien.info/schriftenreihe/2869

Ghosh, S. (2001). Queer Pleasures for Queer People. Film, Television, and Queer Sexuality in India. In R. Vanita (Ed.), Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Ghosh, S. (2010). The Wonderful World of Queer Cinephilia. BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies, 1(1), 21 –25.

Haynes, D. E. (2012). Selling Masculinity: Advertisements for Sex Tonics and the Making of Modern Conjugality in Western India, 1900–1945. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 1–45.

Holtz-Bacha, C. (Ed.). (2008). Stereotype? Frauen und Männer in der Werbung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com.ludwig.lub.lu.se/content/w8p2926251p97541/

Jolly, S. (2002). Gender and Cultural Change. Bridge. Development – Gender, (Overview report). Retrieved from http://74.125.155.132/scholar?q=cache:beZwZDe_MsIJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=de&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1

Khan, S. (2011). Recovering the past in Jodhaa Akbar: masculinities, femininities and cultural politics in Bombay cinema. Feminist Review, 99, 131–146. doi:10.1057/fr.2010.30

Kumar, R. (1997). The History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India 1800-1990. New Delhi: Zubaan.

Mankekar, P. (1993). National Texts and Gendered Lives: An Ethnography of Television Viewers in a North Indian City. American Ethnologist, 20(3), 543–563.

Munshi, S. (1998). Wife/mother/daughter-in-law: multiple avatars of homemaker in 1990s Indian advertising. Media, Culture & Society, 20(4), 573 –591.

Munshi, S. (2001). Images of the Modern Woman in Asia: Global Media, Local Meanings. New Delhi: Routledge.

Munshi, S. (2009). Prime Time Soap Operas on Indian Television (1st ed.). New Delhi: Routledge.

Muraleedharan, T. (2001). Queer Bonds. Male Friendships in Contemporary Malayalam Cinema. In R. Vanita (Ed.), Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Murthy & Dasgupta, L. & R. (2011). Our Pictures, Our Words: A visual Journey through the Women’s Movement. New Delhi: Zubaan. Retrieved from http://www.zubaanbooks.com/zubaan_books_details.asp?BookID=182

NA. (2006). Poster Women: A Visual History of the Women’s Movement in India. New Delhi: Zubaan Books.

Nigam, D., & Jha, J. (2007). Women in advertising: changing perceptions. Hyderabad, India: ICFAI University Press.

Patel, G. (2001). On Fire. Sexuality and its Incitements. In R. Vanita (Ed.), Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Patowary, H. (2014). Portrayal of Women in Indian Mass Media: An Investigation. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 1(1), 84–92.

Rajagopal, A. (1999). Thinking about the New Indian Middle Class: Gender, Advertising, and Politics in an Age of Globalization. In R. S. Rajan (Ed.), Signposts: Gender Issues in Post-independence India (pp. 185–223). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Rao, L. (2001). Facets of Media and Gender Studies in India. Feminist Media Studies, 1(1), 45–48.

Sardana, R. (Ed.). (1984). Indian Women in Media: Focus on Womenʼs Issues : a Collection of Essays. Delhi: Lithouse Publications.

Schaffter, S. J. (2006). Privileging the Privileged: Gender in Indian Advertising. New Delhi: Promilla; Bibliophile South Asia.

Schneider, N.-C. (2013). More than a belated Gutenberg Age: Daily Newspapers in India. An Overview of the Print Media Development since the 1980s, Key Issues and Current Perspectives. Global Media Journal. Retrieved December 19, 2013, from http://www.globalmediajournal.de/2013/12/16/more-than-a-belated-gutenberg-age-daily-newspapers-in-india-an-overview-of-the-print-media-development-since-the-1980s-key-issues-and-current-perspectives/

Sengupta, S. (2014). Ideology of the Lips: Feminine Desire, Politics of Images and Metaphorization of Body in Global Consumerism. In D. Banerjee (Ed.), Boundaries of the Self. Gender, Culture and Spaces. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Retrieved from https://groups.google.com/forum/#!msg/iquestion/h0kxd0rcNYY/g28CNWkExAkJ

Sharma, A. K., & Sharma, R. (2007). Impact of mass media on knowledge about tuberculosis control among homemakers in Delhi. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease: The Official Journal of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 11(8), 893–897.

Stivens, M. (2006). Thinking (again) about gender in Asia. N I A S Nytt: Asia Insight., 15(15). Retrieved from http://nias.ku.dk/sites/default/files/files/8DB31d01.pdf

Uberoi, P. (1996). Social reform, sexuality, and the state. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Vanita, R. (2001). Homophobic Fiction/ Homoerotic Adversiting. The pleasures and Perils of Twentieth-Century Indianess. In R. Vanita (Ed.), Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society (1st ed., pp. 127–148). New York: Routledge.

Vasudevan, R. S. (2000). Sexuality and the Film Apparatus. In J. Nair & M. E. John (Eds.), A question of silence: the sexual economies of modern India. New York: Zed Books.

Vilanilam, J. V. (2009). Development Communication in Practice. sage. Retrieved from http://www.bokkilden.no/SamboWeb/produkt.do?produktId=4023802

Wandrekar, K. (2010). The Endangered Gender: Images of Women in Advertisements. In K. D. Bhavani & C. Vijayasree (Eds.), Woman as Spectator and Spectacle (pp. 34–39). New Delhi: Cambridge University Press India Pvt. Ltd.

Yakkaldevi, A. (2014). Portrayal of Women in Indian Media. Reviews of Literature, 1(8). Retrieved from http://www.reviewsofliterature.org/UploadArticle/148.pdf

Indonesia falls for a remake of the Mahabharata

Photo above (The Caravan/ANTV): Shaheer Sheikh, who played Arjuna in Star Plus’s 2013 Mahabharat, is now the star of a reality television show – See more at: http://www.caravanmagazine.in/lede/love-god#sthash.sBJkWOrw.dpuf

By Pallavi Aiyar (The Caravan, Dec 2014)

ON A SATURDAY AFTERNOON in late September, gaggles of hijab-clad women, many with young children in tow, swarmed outside the closed gates of an auditorium in Taman Mini, a popular recreational park in east Jakarta. A brawny, black-maned figure wielding a bow and arrow pouted suggestively from a phalanx of promotional banners that lined the street, with the title Panah Asmara Arjuna—Arjuna’s Arrow of Love—printed above.

Inside, a stage featuring two giant gilt thrones was being readied. Strobe lights criss-crossed the auditorium, and an overwrought score thundered from the sound system. This was the set for the live broadcast of Panah Asmara Arjuna’s second weekly elimination round. Advertised as a “maha reality show,” the Indonesian series follows a familiar trope: 15 young women start out sharing a house, and compete in daily challenges as they vie for the attention of a desirable hero. But in this case the hero happens to be someone who speaks no Indonesian, and had only been in the country for about a month when the show started: the Indian actor Shaheer Sheikh, who played Arjuna in the 2013 television series Mahabharat, an extravagant adaptation of the mythological epic by Star Plus. Every Saturday, the women line up on a stage, dubbed the “bharata yudha” zone, and Sheikh sends one of them home. The winner, who will be announced at the end of December, will travel with Sheikh to India.

The Indonesian channel ANTV bought the rights to the Mahabharat from Star Plus, and started airing a dubbed version of the show this March. I first came across this Bahasa Indonesia Mahabharat in June, when I began to tune into ANTV every evening for its exclusive regional broadcasts of the FIFA World Cup. Mahabharat was aired just prior to each day’s opening matches. As I waited for well-built men to take to the football field, I ended up watching well-built men in faux-gold jewellery fighting with magical weapons instead. ANTV soon discovered that the ratings for the mythological series were higher than those for the football. At its peak, the show reached 7.6 percent of Indonesia’s television viewership; the World Cup final reached only 6.2 percent.

I met with Kelly da Cunha, ANTV’s general manager of production, in a boxy backstage room a few hours before filming for the Panah elimination round was to begin. Middle-aged and portly, da Cunha chuckled compulsively while recounting the numbers. “With these kinds of ratings, we decided to go further,” he explained. Early this October, ANTV brought sevenMahabharat cast members over from India to perform in a live, three-hour stage show in Jakarta. The programme consisted of interviews and assorted histrionics—such as the five Pandavas and their archenemies, Duryodhana and Karna, gyrating to music that, though loud, could not drown out the ululations of the hundreds-strong, largely female audience.

The popularity of a show based on the Mahabharata in Muslim-majority Indonesia might seem surprising, but da Cunha explained that Hindu epics are part of the country’s culture. For centuries, many parts of the Indonesian archipelago were majority-Hindu. By the seventh century CE, Hindu–Buddhist kingdoms dominated both Java and Sumatra—Indonesia’s two most populous islands. Ever since, Hindu cultural norms have infused indigenous mores, even after large-scale conversion to Islam in the sixteenth century.

References to the epics are everywhere in Java—the language, the street signs, the political commentary. In Jakarta, many buses are painted with lurid advertisements for an energy drink called Kuku Bima, which promises Bhima-like endurance. An enormous statue of Krishna leading Arjun into battle dominates the roundabout in front of the Monas, the country’s main nationalist monument. There is a nationwide charitable foundation for twins named the Nakula and Sadewa Society. And one of the country’s bestselling novels, Amba, uses the story of Bhishma and Shikhandi (a later incarnation of Amba) to talk about Indonesia’s purges of communists in the mid 1960s.

Wayang kulit, a form of shadow-puppet theatre that features tales from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, can draw tens of thousands to performances in rural Java. Indonesians feel a real sense of ownership over the epics. In the mid nineteenth century, Ronggowarsito, a poet from a royal court in central Java, wrote an apocryphal history that traced the lineage of the Javanese kings back to the Pandavas. Eventually, many

Indonesians came to believe that the Mahabharta was set in Java rather than India.

But India still has special appeal. Da Cunha said that after ANTV aired the Star Plus Mahabharat, a rival channel began to broadcast an all-Indonesian version of the epic, Ksatria Pandawa Lima whose title translates to the “Five Pandava Knights.” The show flopped. The reason, da Cunha claimed, was that a local “copy” could not compare to the “Indian original.”

Da Cunha added that stories from the Hindu epics are not really associated with religion by Indonesian audiences. Instead, they are understood as morality tales that happen to be embedded in the local culture. “Even Shaheer is a Muslim,” he pointed out, “so there is nothing religious here.”

I heard much the same thing when, last year, I met Ki Purbo Asmoro, one of Indonesia’s most celebrated wayang kulit masters, or dalang. Like most dalang, and like most wayang kulit audiences, Purbo Asmoro is Muslim. “These stories are allegorical,” he told me. “None of us take them as the literal truth.” He also said the Hindu epics promote values—for instance, the loyalty, courage and integrity of characters such as Ghatotkach and Bhim—that are affirmed by Islam. But those parallels aren’t essential; for many Indonesians, the Mahabharat is pure entertainment, akin to shows such as the hit HBO fantasy series Game of Thrones except with greater cultural resonance.

Backstage on the Panah set, I also met Mahabharata actors Vin Rana and Lavanya Bharadwaj, who played, respectively, the twins Nakula and Sahadeva. Following the Jakarta stage show in October, in which they both took part, ANTV took the cast to Bali, the only island in Indonesia that remains predominantly Hindu today. They were met in person, the actors told me, by the Raja of Ubud, a Balinese town. Bharadwaj, a youngster from Meerut, recalled a Balinese fan ferreting away in her handbag, as though it were a treasure, an apple that he had half eaten. Rana, formerly a heavy-machinery parts importer from Pitampura in Delhi, spoke of a woman fainting when she saw him in the flesh.

“They respect us so much over here,” Rana said solemnly. “Respect or desire?” I asked. He giggled nervously. Acquiring sex-symbol status by playing demigods has put the television Pandavas on awkward terrain.

Meanwhile, “Arjuna” was gearing up for the stage. Sheikh listened intently, through an interpreter, to a headscarved young woman running him through the evening. Dressed casually, in sports clothes stretched tight across his muscular torso, he swatted with impressive accuracy at mosquitoes buzzing around the room.

With his shoulder-length hair and well-defined six-pack, it was easy to see why the Jammu-born actor is the most popular member of the Mahabharat cast in Indonesia. Sheikh boasts 262,000 Twitter followers, the vast majority of whom, he said, are Indonesian. On the first day the dubbed Mahabharat was broadcast in the Twitter-mad country, he said, his following jumped by 30,000.

Sheikh explained that when he was first approached to play the role of Arjuna, he had been reluctant, in part because his Hindi was poor. Once he accepted, he spent months in preparation, taking lessons in Hindi diction, learning to ride horses and handle weapons. He feels the role has changed him. Studying the Bhagwad Gita, he said, has been crucial in helping him make difficult choices. But it was unlikely to help with the toughest choice he faced that evening: which young woman to eliminate from the show.

In the broadcast, Sheikh was confronted by 14 contestants, or dewis, resplendent in anarkali-style kurtas. Over almost two and a half hours of high drama occasionally punctuated by dancing, he whittled the group down to five candidates for elimination. The girl he eventually sent away

managed a wan smile when Sheikh pressed a locket he was wearing upon her as a keepsake. The episode concluded with “Arjuna” and the dewis dancing to the Bollywood hit ‘London thumakda.’

ANTV hopes to cash in even further on the Mahabharat craze. It intends to broadcast another live stage show from Jakarta this month, with an expanded cast including the Mahabharat characters of Bhishma, Draupadi, Shakuni and Kunti in addition to the five Pandavas. In a bit of cross-epic fertilisation, the channel also plans to invite the actors who played Rama, Sita and Hanuman in Zee TV’s 2012 Ramayana (which ANTV dubbed and aired earlier this year as well).

Da Cuhna told me he believes the “soft power” of Indian pop culture has great potential in Indonesia. A year ago the craze was for Korean pop and culture, he said, but “at ANTV we want to replace that with Indian pop.” The channel plans to market Indian fashion accessories, clothes and music in addition to airing imported television serials. Da Cuhna, who has made a career of spotting cultural trends, was bullish: “India is going to be the new Korea of culture.”

Pallavi Aiyar is an award-winning journalist and author, currently based in Jakarta. Her books include Punjabi Parmesan: Dispatches from a Europe in Crisis, Smoke and Mirrors, and Chinese Whiskers.

– See more at: http://www.caravanmagazine.in/lede/love-god#sthash.sBJkWOrw.dpuf

News » National

Published: January 16, 2015 08:08 IST | Updated: January 17, 2015 00:58 IST

Furore as Leela Samson quits

Even as the Government challenged Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) `chairperson’ Leela Samson to prove her allegations, her decision to step down is expected to trigger a slew of resignations from the Board over the weekend. Already, one member, Ira Bhasker, is learnt to have stepped down.

Citing „interference, coercion’’ besides corruption of panel members and officers of the organization appointed by the Information & Broadcasting (I&B) Ministry, Ms. Samson sent in her resignation on Thursday night soon after word came that the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) had cleared the release of the film MSG – The Messenger of God featuring Dera Saccha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insan.

The film was initially scheduled for release today but was postponed after the `Examining Committee’ and the `Revising Committee’ of the CBFC rejected certification for the film. The `Revising Committee’ referred the film to FCAT last Tuesday and what has stunned Ms. Samson and other members of the Board is the speed at which the tribunal cleared the film.

„It usually takes FCAT several weeks to clear a film referred to it,’’ said one member who did not want to be quoted.

Meanwhile, the premiere of the film that was hurriedly sought to be organised in the satellite township of Gurgaon, adjoining Delhi, on Friday evening was cancelled at the eleventh hour as necessary formalities had not been completed. The Dera chief told his followers who had gathered there in large numbers that the date of the premiere and release of the film would be announced later. Prior to FCAT approval, the Dera had rescheduled the release of the film for January 23 but from what Ram Rahim told his followers that could also now change.

The FCAT’s decision drew sporadic protests in many parts of Punjab and Haryana. The Akal Takht had in December sought a ban on the movie by the godman who had first hurt the sentiments of the community when he had allegedly dressed up like the Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh. Several radical Sikh organizations like the Dal Khalsa and the Peer Mohammad faction of the All India Sikh Students Federation had also supported the demand then.

As the Government drew flak for the charges levelled by Ms. Samson, Union Minister of State for I&B Rajyavardhan Rathore countered by asking her to show a „letter or an SMS’’ to prove that the government had been ignoring the CBFC’s requests and preventing the Board from meeting for the past nine months. Two CBFC members confirmed to The Hindu that the Board had not met even once in the past nine months.

Ms. Samson’s three-year term and that of many of the Board members had ended in May 2014. In July, the Ministry had informed the Board members that their term was being extended „till further notice“.

Recently, the Board had also come under pressure from members of the Sangh Parivar over the Amir Khan-starrer `PK‘. At that point, Ms. Samson had gone on record stating that no scene from the film would be removed as it had already been released.

In the midst of the controversy, she had said over a fortnight ago that: „Every film may hurt religious sentiments of somebody or the other. We can’t remove scenes unnecessarily because there is something called creative endeavour where people present things in their own way. We have already given certificate to `PK‘ and we can’t remove anything now because it’s already out for public viewing.“

Keywords: Leela Samson, Censor Board, Messenger of God, Dera Saccha Sauda

View comments (74)

Printable version | Jan 17, 2015 12:28:48 PM | http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/censor-board-chief-leela-samson-decides-to-quit/article6792822.ece

© The Hindu

Related articles: PK Controversy: 5 reasons why the film must be banned (India Today)

PK: Controversies and laurels (The Hindu online)

Vortrag von Maria Rost, 15.- 21. Dezember 2014, Bombay.

Inszenierung oder Zeugnis interkultureller Kompetenz? Indienbilder und Selbstwahrnehmung deutschsprachiger Reisender in Online-Reiseberichten

Medien beeinflussen heutzutage immer mehr unseren Alltag. Sie verbreiten Bilder, mentale wie materielle. Aber auch wer ein gutes Buch liest, versinkt in eine andere Welt. Ein gut gemachter Reisebericht kann Vorstellungen erweitern und einen Perspektivwechsel anregen. Die Frage, die ich mir stelle ist, welche Funktion Reiseberichte heutzutage haben. Nach wie vor produzieren und transferieren Reiseberichte Images, Repräsentationen und Konnotationen von Wahrnehmungen und Sehgewohnheiten. Mit ihren Darstellungen beeinflussen die Schreibenden also ganz klar das Bewusstsein ihrer Leser_innen. Genau das kann auch ein gut strukturierter und spannend gestalteter Weblog über das Reisen in Indien erreichen. Die Aufzeichnungen geben Einblicke in individuelle Erfahrungsverarbeitungen und beeinflussen somit das Bild der Destination Indien, eben auch durch ihr Veröffentlichungsmedium.

Online-Reiseberichte stellen uns vor die Aufgabe, interdisziplinär zu arbeiten und intermedial zu denken. Dabei besteht die Herausforderung darin, bisher eher getrennt betrachtet Medien von Text und Bild zusammenzubringen und unter gemeinsamen Schwerpunkten vergleichend oder ergänzend zu untersuchen. Die Geschichte der Reisefotografie und der Reiseliteratur über Indien weist erstaunlich viele Parallelen auf in Bezug auf Entwicklungen von Funktion, Bild und Perspektive.

Wenn wir uns nun aktuellen Online-Reiseberichten zuwenden lässt sich zunächst erst einmal festhalten, dass Reiseberichte über Indien nach wie vor präsent sind und sich eines breiten Lesepublikums erfreuen. Reiseliteratur ist also nicht auf dem absteigenden Ast, wie es Anfang der 1990er Jahre oft geheißen hat. Durch Reiseliteraturverlage mit dem Konzept des ‚print on demand‘ und die Möglichkeit der selbstverlegerischen Veröffentlichung können Reisende unkompliziert ihre Reiseerfahrungen veröffentlichen. Und durch die Expansion des Mediensystems findet Reiseliteratur eine weite Verbreitung. Meine Untersuchungen führen zu der grundsätzlichen Annahme, dass Reiseberichte über Indien keinem Funktionsverlust unterliegen, sondern einen Funktionswandel vollziehen. So dienen Online-Reiseberichte gegenwärtig eher als Orientierungshilfe und Informationsquelle für zukünftige eigene Reisen. Daher ist es wichtig, nicht nur das Schöne zu beschreiben, sondern auch das Unwegsame: Die Mischung aus Fakten und Genuss- und Erlebnis-Aspekten macht einen informativen Weblog aus. Denn fern vom alltäglich Gewohnten entstehen neue Imaginationen und somit neue ästhetische Topographien des Reisens. Die geposteten Bilder haben dabei eine unterstützende Funktion: Sie sollen in Reisestimmung versetzen und können in ihrer ästhetischen Funktion den interkulturellen Dialog anregen.

In einem Untersuchungsprozess geht es daher weniger darum, das ‚Andere‘ als eine zentrale Kategorie herauszuarbeiten. Vielmehr beobachte ich, dass die Darstellung des ‚Exotischen‘ in den Online-Reiseberichten über Indien keine tragende Rolle mehr spielt. Der Topos vom ‚Eigenen‘ und ‚Fremden‘ wird gegenwärtig durch eine veränderte Schwerpunktsetzung verdrängt. Dabei nimmt die Visualisierung interkultureller Aspekte durch rasante technische Entwicklungen genauso wie durch physische und mediale Mobilität zu. Neben sprachlichen und mentalen Bildern ist Fotografie ein Medium das dazu beiträgt, Konzepte von Ästhetik neu zu bewerten.

Um das Bedeutungspotential von Literatur zur Illustration von Interkulturalität produktiv erschließen zu können ist es daher notwendig, neue Medien in den Untersuchungsprozess zu integrieren und transmedial zu denken. Alle aufgeführten Punkte verdeutlichen, dass internetbasierte Reiseberichte ein zentraler Bereich des internationalen und interkulturellen Dialog sind, so auch zwischen Indien und Deutschland.