Four questions for Deepak Kashyap

In the summer of 2025, Deepak Kashyap, a doctoral candidate from JNU, our partner university in Delhi, embarked on a three-month research internship at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, delving into the unexpected cricket culture flourishing in the city. In this conversation, Deepak shares how the research internship offered a structured, hands-on approach to research, blending academic rigor with meaningful cultural exchange. From exploring the unique dynamics of cricket in Berlin to reflecting on his own role as a researcher, Deepak Kashyap discusses how the experience shaped his understanding of both the sport and his academic journey.

Deepak Kashyap during a presentation of his research at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (c) NCS

How do you perceive your role as a research intern in comparison to being a student or doctoral candidate at the university? Do you feel that your perspective and responsibilities have shifted significantly?

In my understanding, my role as a research intern is significantly different than being a student or a doctoral student at the university. Because of the time-bound nature of the internship, it is more rigorous in terms of frequency and regularity. Having a shared office within the institute has proved immensely beneficial, especially during brainstorming sessions and mutual knowledge exchange. At the same time, I realize that being enrolled as a student at the university would have opened up more pathways for me in terms of the offered courses and diversity of friend circles. In comparison to a doctoral candidate, I find the internship more structured and focused.

Yes, there is a considerable shift in perspective and responsibilities. From my experience as a doctoral student at JNU, I can say that this internship allowed for more human interaction while doing research work. The paperwork for scholarship was not a problem with HU. The research colloquium organised monthly, combined with weekly talks, gave substantial impetus to engage with interdisciplinary work within the framework of the research project.

What inspired you to explore cricket in Berlin, and what aspects of this research topic have you found most intriguing or surprising?

The phenomenon of people playing cricket in Berlin was first mentioned during our initial rounds of presentation for the research project. I was a bit surprised on getting to know about such practice because in Europe cricket is a relatively lesser-known sport. It piqued my interest because I wanted to find out how the sport is perceived by the inhabitants of Berlin. I also wondered in which spaces is the sport being played and how the organization of cricket matches and/or leagues work.

I had only watched the sport on television and played myself as a child. This research project provided me an opportune moment to engage with sports academically and study it from a perspective of migration and diaspora studies, urban geography, and leisure studies.

What has your experience been like living and working in Berlin, and how has it influenced your understanding of cricket’s cultural significance in the city?

In terms of studying and working academically in Berlin, the experience has been emphatically wonderful. In the initial few days, I was still learning to get around in the university system. The ready availability and range of accessible books has given a rich, multidisciplinary direction to the research. The regular interaction with the work of other academics was beneficial in incorporating pertinent idea to my study. I could, at any point of time, write an email to my supervisor to address in case of concerns regarding the project.

These interactions, within and outside the department, brought to my attentions themes such as leisure, nationalism, and nostalgia, which I had been overlooking initially. Through some suggestions, I had also been able to come to view my agency and involvement in the project. This adds an autobiographical layer to the project where I am not a non-participating outsider.

Personally, the various amenities offered by the university such as the MensaCard, Deutschlandticket, and free NextBike services made getting around the city easier.

What is the question you’ve found yourself reflecting on most during your three-month research internship at HU Berlin?

The most pressing work-related question that I had during my stay in Berlin was how could my study help the cricket-playing community in Berlin. Currently, the infrastructure in the city for cricket is quite inadequate. If I could in any way bring the benefits of my study in the real world and somehow contribute to improve the game in Berlin, it could really go a long way.

(the questions were asked by Nadja-Christina Schneider)

Four questions for Arya Lovekar

In the heart of Berlin’s vibrant and multifaceted food scene, South Asian chefs and culinary practitioners play a key role in navigating the complex web of cultural practice and mediation. As part of the Humboldt Internship Program, Arya Lovekar embarked on a journey to explore the ways in which food, as both an everyday necessity and cultural practice, bridges divides within the South Asian diaspora in Berlin. Arya’s research investigates how Indian and South Asian chefs construct cultural identities through food in response to both the diverse Berlin environment and the expectations of their various customer groups. In this conversation, Arya shares experiences, challenges and insights, shedding light on the role of food in cultural representation, identity-building and community cohesion across the diasporic landscape.

Arya Lovekar during a research presentation at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (c) NCS

As a research intern, how do you view your role within the research process in comparison to that of an MA student? Have your responsibilities and your perspective on the university evolved throughout the course of your internship?

As a research intern, I had much more flexibility in my research than as an MA student, where I am more limited by the disciplinary boundaries of my degree program. For the research internship, I was able to use multiple disciplinary lenses where applicable, and I found this very useful when designing the methodology of the project. Meeting other researchers at various levels in their careers has also helped me understand how I and the work I am interested in might fit into a university structure. Working as part of a larger project was a useful guideline, and it helped focus my work.

What inspired you to focus your research on chefs and restaurants in Berlin, and how do you see their role in bridging cultural gaps through food?

My brief time working in an Indian restaurant and the experience of cooking for myself and others as a migrant to Belgium made me think a lot about how food can connect or divide people, within and across communities that are uniquely imagined by every person in the group. I wanted to focus on chefs and restaurants partly because they are methodologically easier to access than people’s food practices in their homes, but also because restaurants are a site for discussing and sharing food with those who may be unfamiliar with it. When restaurants present food to their customers, they are constructing an image of their claimed culture and the wants of their customer base, and this means that it is not only food that is conveyed, but notions of how a people engages in this most mundane and everyday activity of eating. The image of a community can be built for supposed insiders and outsiders in such a setting, and many cultural tensions contribute to the construction of this image, all through food, which is not merely sustenance but an active cultural practice.

What insights have you gained about the diversity of food cultures in Berlin, and how does the city’s pluricultural environment shape the way Indian and South Asian chefs tailor their dishes to different customer groups?

I have learned that diaspora carry their social beliefs with them in a new country and express them through their food, and that there is a contradiction between the diversity and uniformity of food cultures in Berlin. Although there are many food cultures here, each one is often internally uniform, prioritising certain sections of the diaspora even from the same part of the world. As a result, when those not from South Asia eat South Asian food in Berlin, they are learning about a very carefully constructed image of South Asia. This image has been constructed with reference to social divides within South Asian, but also with the aim of sanitising and re-writing South Asia for a ‘Western’ audience, indicating a type of contemporary self-Orientalising. South Asian food benefits from Berlin’s culture of veganism and restaurants that serve South Asian food often underline that vegan and vegetarian food appears frequently in the standard fare from this part of the world.

What question has most frequently shaped your thinking during your research, and how has your perspective on the role of chefs in Berlin evolved throughout your internship?

I have been trying to understand what the ‘right’ way is for a South Asian migrant to construct themselves in the public eye in Berlin. Each migrant I have spoken to has made their own self-image to cater to so many different social tensions, and this aligns with my own experience as a migrant in Belgium and now in Berlin.

I started out seeing chefs in Berlin as somewhat romanticised figures, bringing their heritage with them and starting restaurants out of a love for food and cultural exchange. While I expected to see some deviations from this, I had not realised that much of this narrative comes from the public image of specific restaurants who wish to (truthfully or not) present themselves in this way. I found it more useful to think of the restaurant as a whole as a cultural practitioner, with all the individuals who work there entering this setting with their own reasons for participating in this cultural practice.

I enjoyed my conversations with restaurant managers, cooks, and waiters during this project, as well as with migrants not in the restaurant industry but with interesting relationships with what they perceived as “their” food. I unexpectedly spoke at length with a bookstore owner about the experience of being a migrant and eating with others. I learned that speaking in Hindi will get me further in these con-versations than English will. I learned that some people are more suspicious of people asking

questions as I did, while others are happy to tell me startling things I did not ask about, but nevertheless found fascinating.

It turns out that it is possible to find both connection and great loneliness in these

conversations, and sometimes both at once. I think there is a lot more to learn here, and more very interesting people I hope to talk to about this in the future.

(the questions were asked by Nadja-Christina Schneider)

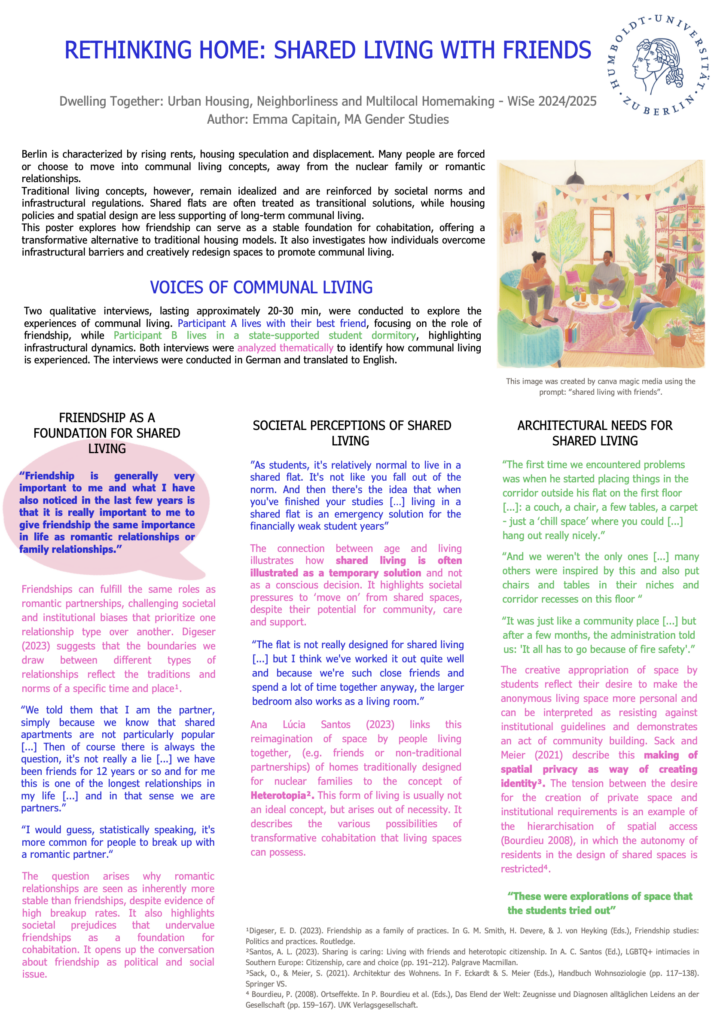

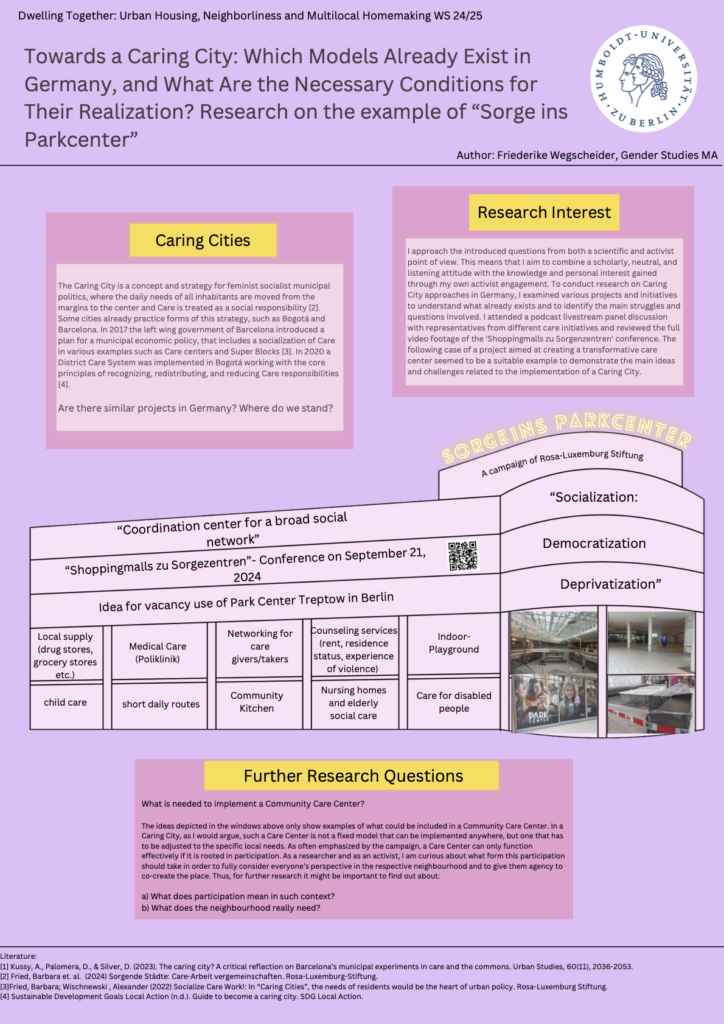

The four posters were created as part of our research seminar in the winter semester of 2024/25, offering an insight into the projects that participants worked on intensively over the course of the semester. In the first part of the seminar, we explored critical perspectives from practitioners, filmmakers and scholars on topics such as affordable housing amid market-driven construction and land shortages, architecture and infrastructure that support the well-being of humans (and potentially other species) in cities, peri-urban, and rural areas, as well as neighborhood and coexistence in urban contexts. Research findings from a spatial design perspective were also discussed, covering topics like living and temporary homemaking on university campuses, cohabitation in rapidly changing neighborhoods, post-disaster housing and community building as well as multilocal living arrangements across regions or national borders. Based on this, participants developed their own student research projects in the second part of the seminar, which were continuously refined through exchange with the seminar instructor and peers.

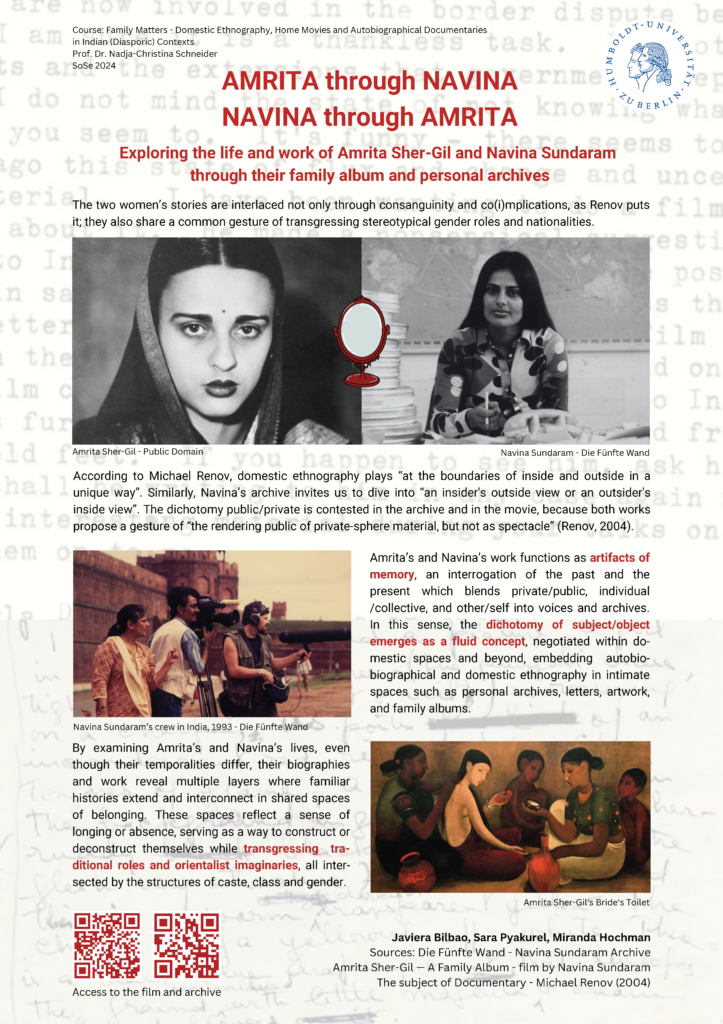

In this seminar, a group of international students from the HU Master’s programs in Asian/African Studies, Gender Studies, Global Studies and History (both MA and BA) explored the methodological approach of visual domestic ethnography as it has been theorized by film scholar Michael Renov and later on extended by Nariman Massoumi and other authors & filmmakers. The students applied this approach to selected autobiographical family films by South Asian film directors made since the end of the 1990s. Their posters were created as part of our seminar. They also contain QR codes that can be used to view the films examined online.

Studentische Wohnungsnot in Berlin

von Nadja-Christina Schneider1

Für Studierende wird es in einer Stadt wie Berlin seit Jahren immer schwieriger, eine bezahlbare Unterkunft zu finden. Lange Wartelisten für Wohnheimplätze, die WG-Zimmersuche als herausfordernder Casting-Wettbewerb und für viele kaum bezahlbare Mieten. Wohnen „außerhalb“ ist bekanntlich keine attraktive Alternative für junge Menschen, die es in dieser besonders prägenden Phase ihres Lebens in die Großstadt zieht. Lange Anfahrtswege, eine mitunter schlechte Anbindung an öffentliche Verkehrsmittel und das Fehlen anderer wichtiger Infrastrukturen des täglichen Lebens möchten viele ebenfalls nicht in Kauf nehmen. Inmitten der allgemeinen Wohnungsnot in Berlin fange „die studentische Wohnungskrise erst an“, so formulierte es der Tagesspiegel am 22. Dezember 2022.

Wie David Madden und Peter Marcuse in ihrem gemeinsam verfassten Buch In Defense of Housing (2016) kritisieren, vermittelt der vielzitierte Begriff der Wohnungskrise, dass es sich lediglich um eine temporäre Abweichung von einem ansonsten weitaus besseren Normalzustand handele, der mit den richtigen Maßnahmen wiederhergestellt werden könnte, wie es insbesondere die politische Rhetorik nahelegt.2[1] Madden und Marcuse erinnern jedoch daran, dass bereits Friedrich Engels in seinen Überlegungen zur Wohnungsfrage (1887) erkannt hatte, für welche gesellschaftlichen Gruppen diese „Krise“ zu allen Zeiten tatsächlich den Normalzustand darstellt:

„The so-called housing shortage, which plays such a great role in the press nowadays, does not consist in the fact that the working class generally lives in bad, overcrowded or unhealthy dwellings. This shortage is not something peculiar to the present; it is not even one of the sufferings peculiar to the modern proletariat in contradistinction to all earlier oppressed classes. On the contrary, all oppressed classes in all periods suffered more or less uniformly from it (F. Engels (1872). The Housing Question, zitiert in Madden & Marcuse 2016: 9).”

Die neue Wohnungsfrage im Berlin des 21. Jahrhunderts ist in den sog. klassischen Medien durchaus sichtbar, aber es fällt schnell auf, welche gesellschaftlichen Gruppen keine besonders hohe mediale Aufmerksamkeit erhalten. Studierende gehören ohne Zweifel dazu, denn abgesehen von einigen Schlagzeilen und Zeitungsberichten, welche regelmäßig zum Semesterbeginn zu finden sind, hält sich die Berichterstattung zur studentischen Wohnungsnot in der deutschen Hauptstadt in Grenzen.

Woran könnte das liegen, zumal in einer Stadt, die sich als „engagierte, exzellente und internationale Brain City“ beziehungsweise als „innovative Wissensmetropole“ versteht und in der es in der Tat eine beachtliche Zahl an öffentlichen und privaten Universitäten sowie Hochschulen gibt? Nach Angaben der Berliner Senatsseiten forschen, lehren, arbeiten und studieren „an den elf staatlichen, zwei konfessionellen und rund 30 staatlich anerkannten Hochschulen in Berlin über 250.000 Menschen aus aller Welt.“3[2] Wie finden all diese Hochschulangehörigen ihren bezahlbaren Wohnraum in Berlin und wo wohnen sie?

Auch ein Blick auf die zentralen Webseiten der drei großen Berliner Universitäten TU, HU und FU weist das Thema studentisches Wohnen und die Wohnungsnot der Studierenden nicht als eines aus, für das sich die Bildungseinrichtungen selbst in zentraler Verantwortung sehen oder über das sie sonderlich viel zu berichten hätten. Die wenigen auffindbaren Informationen richten sich vorwiegend an internationale Studierende oder verweisen auf die Angebote des Studierendenwerks bzw. im Fall der HU auf den Campus in Adlershof. Wie Judith Thomsen in ihrer Studie zu „Home Experiences in Student Housing“ (2007) mit Bezug auf Norwegen erwähnt, werden Unterkünfte für ihre Studierenden nicht nur in Deutschland, sondern auch in Skandinavien traditionell nicht als Bereich betrachtet, für den die Universitäten als verantwortlich gesehen werden. Sie führt jedoch Großbritannien als Beispiel für einige westeuropäische Länder an, in denen „university-provided student housing“ zumindest über längere Zeiträume existierten (Thomsen 2007: 578).

Da studentisches Wohnen in Berlin offenbar weiterhin als ein Bereich betrachtet wird, der buchstäblich „außerhalb“ der Universität liegt, müssen Studierende selbst eine Lösung hierfür finden. Gelingt es nicht, wird dies von jungen Menschen häufig als „Scheitern“ oder ungewollte Rückkehr in die Phase der Adoleszenz wahrgenommen. Besonders deutlich wurde dies in der Pandemie-Situation, in der sich Studierende in hoher Zahl gezwungen sehen, wieder bei ihren Eltern und vielfach in ihr altes Kinderzimmer einzuziehen, das nach ihrem Auszug eigentlich für ihre Wochenendbesuche oder andere Zwecke genutzt werden sollte. Für viele Studierende auf Wohnungssuche in Berlin, darunter ein hoher Anteil an internationalen Studierenden, gab und gibt es jedoch nicht einmal diese Option eines „Zurück zu…“ oder sie versuchen, den Wegzug aus der Stadt, in die sie mit so vielen Hoffnungen und Erwartungen gekommen sind, doch noch irgendwie abwenden zu können. Es ist ein sehr wichtiger Schritt, dass wir an den Berliner Universitäten mittlerweile immer mehr Bewusstsein und auch Angebote für zentrale Fragen der mentalen Gesundheit von Studierenden bereitstellen. Doch wir verknüpfen diese bislang noch nicht mit der außerordentlich hohen Belastung, der sie in vielen Fällen in erster Linie aufgrund ihrer Wohnsituation und finanziellen Probleme und möglicherweise nicht primär durch ihr Studium ausgesetzt sind.

Im deutlichen Kontrast zur Abwesenheit der Wohnungsnot von Studierenden in den „klassischen“ Medien weisen soziale Medien und Plattformen wie YouTube neuerdings eine wachsende Zahl an hochgeladenen Beiträgen zu diesem Thema auf. Darin lassen sich wiederum unterschiedlichste Formate und damit verknüpfte Medienpraktiken feststellen, welche von einer medialen Selbstpräsentation der Studierenden und Thematisierung ihrer aktuellen Wohnsituation oder verzweifelten Suche über dialogische Formate und Tipps für andere Studierende bis zu einfach hochgeladenen Videos mit Informationen und Testimonial-Berichten reichen können. Auffallend ist auch hier, dass sich viele der Austausch- und Informationsangebote gezielt an internationale Studierende in Berlin richten.

Home Abroad Podcast: Student Accommodation in Berlin

Rishi: „Berlin Housing is a little bit like a Hunger Games.”

Ellie: “Hahaha. Fight to the death for it.”

Eines der am häufigsten aufgerufenen Beispiele hierfür ist ein knapp fünfminütiges Video, das für internationale Studierende an der Freien Universität produziert wurde und sich überwiegend auf studentische Unterkünfte im Südwesten Berlins bezieht. Neben Studentenwohnheimen und der Unterbringung in Gastfamilien sowie einem kurzen Abstecher an den Alexanderplatz zum kommerziellen The Social Hub (früher The Student Hotel) wird hier das Studentendorf Schlachtensee vorgestellt, nach dessen Vorbild für HU-Studierende das Studentendorf Adlershof neu erbaut wurde. Die interviewte Bewohnerin im FU-Video verrät uns, dass heute überwiegend internationale Studierende im Studentendorf in Schlachtensee ihre temporäre Unterkunft in Berlin finden – ursprünglich errichtet wurde es in der Nachkriegszeit jedoch nicht nur, um dort Studierende der FU unterbringen zu können, sondern auch, um im Rahmen der US-amerikanischen Maßnahmen zur Reeducation junge Menschen in der Bundesrepublik an die Demokratie heranzuführen.

Die Architektur und Raumplanung des Studentendorfes Schlachtensee sollte also dafür Sorge tragen, dass junge Studierende als zentrale Akteursgruppe der bundesdeutschen Nachkriegsgesellschaft lernen, demokratisch zusammen zu leben. Dies mag aus heutiger Sicht als Form eines „social engineering“ und Ausdruck einer top-down-Planung kritisch betrachtet werden. Gerade mit Blick auf den „hyperkommodifizierten“ städtischen Wohnungsmarkt der Gegenwart (Madden & Marcuse 2016: 39) wirft es aber auch die Frage auf, wie die Gesellschaft und Politik eigentlich heute auf die Studierenden und ihre Rolle blickt, und ob sie nicht nur für die Notwendigkeit des studentischen Wohnens erneut sensibilisiert werden könnte, sondern vor allem auch für das positive Potenzial gemeinschaftlichen Wohnens als Erfahrung und eingeübte Praxis, die zu Formen eines gutes Zusammenleben in der Gesellschaft beitragen kann.

Zitierte Literatur

Madden, David and Peter Marcuse (2016). In Defense of Housing. London/New York: Verso.

Thomsen, Judith (2007). “Home Experiences in Student Housing: About Institutional Character and Temporary Homes”. Journal of Youth Studies, 10:5, 577-596.

Über die Autorin

Nadja-Christina Schneider ist Südasienwissenschaftlerin und arbeitet am Institut für Asien- und Afrikawissenschaften. Mit dem Thema bezahlbarer Wohnraum, Architektur und Zusammenleben befasst sie sich seit einigen Jahren intensiver.

- Dieser Text ist aus einer gemeinsamen Schreibübung mit Master-Studierenden hervorgegangen, die wir im Sommersememster 2023 zum Thema studentisches Wohnen, Zusammenleben und bezahlbarer Wohnraum in Berlin im Rahmen eines Seminars durchgeführt haben. Der ebenfalls in diesem Blog veröffentlichte Beitrag von İnci Nazlıcan Sağırbaşbaş zum Thema „Making a Home in Berlin: Navigating a Housing Crisis as an International Student“ ist auch aus dieser Schreibübung im Rahmen unseres Seminars hervorgegangen. ↩︎

- „Klara Geywitz, Bundesministerin für Wohnen, Stadtentwicklung und Bauwesen: ‚Zum ersten Mal gibt es im Rahmen des sozialen Wohnungsbaus ein Förderprogramm nur für junge Menschen in Ausbildung. Sie sollen sich vor allem auf ihre Ausbildung konzentrieren und nicht wochen- oder gar monatelang auf Wohnungssuche sein. Mit einer halben Milliarde Euro können die Länder jetzt Wohnheimplätze neu- oder umbauen, um junge Menschen in die Region zu holen oder zu halten. Damit wird der Standort Deutschland insgesamt attraktiv für junges Knowhow, aber auch die einzelnen Regionen profitieren erheblich. Wer einmal da ist, bleibt vielleicht. Wie gut man Wohnraum findet, den sich jeder leisten kann, ist dabei ein entscheidender Faktor. Mit diesem gezielten Fokus auf Junges Wohnen werden wir sicher schnell Erfolge erzielen‘ („Bezahlbarer Wohnraum für junge Menschen: Sonderprogramm Junges Wohnen gestartet!“ https://www.studentenwerke.de/de/content/bezahlbarer-wohnraum-fue-junge-menschen).“ (10.06.2023) ↩︎

- Senatsverwaltung für Wissenschaft, Gesundheit und Pflege: Wissenschaft und Forschung: Hochschulen. https://www.berlin.de/sen/wissenschaft/einrichtungen/hochschulen/ (10.06.2023). ↩︎

By İnci Nazlıcan Sağırbaşbaş

Regardless of our backgrounds, the concept of home is central to our belonging, it is a matter of feeling comfortable and safer. While the emerging housing crisis in Berlin results in a massive housing shortage, high rent prices, informal housing arrangements, and unjust rental procedures for almost everyone, it adds to the vulnerability of international students who are already in discriminatory and structurally challenging processes. Newly arrived international students are bound to go through various difficulties in finding a relatively stable or affordable place while also struggling with the barriers of language, law, and bureaucracy. They have to constantly navigate the various stereotypes ingrained in people’s minds, while not having the possibility of having a permanent place to live or basic utilities such as ‘a possibility of Anmeldung’.

I want to talk in particular about the experiences of finding a home in Berlin through online portals and the perceptions of the city for some international students through their various practices of home-making. How do these practices of ‘making a home’ such as finding an accommodation, settlement, building support networks, and dealing with the bureaucracy outline and influence the sense of belonging in the city? The process supporting this essay comprises auto-ethnographic research and semi-structured in-depth interviews with a homogeneous sample of international students. The following questions were asked according to the way conversations proceed: What were the biggest obstacles for you in finding housing? How did the process make you feel? What help did you get? How do you think your identity as an immigrant and a student has affected the outcomes? In total, 8 people were interviewed, 6 women and 2 men, all non-EU citizens and from middle-upper classes. The interviews provided limited data on personal and collective behaviors and trajectories while considering the complexity of the relationship between the immigrant’s experience in the city and the role of home-making.

‘While I was looking for an apartment I sent hundreds of messages without any reply, however when my partner with her German last name sent a few messages she got several replies and that’s how we found our first place.’

I, like most of my fellow international students, have looked at and applied to countless flatshares during my first months in Berlin. It became an automatic act to check new offers, answer questions, and send motivational, desperately positive, and personal messages to complete strangers on a daily basis. It was the first thing I did in the morning and the last in the evening. There were several identities crashing into each other in my mind, and I was struggling to describe who I was for the prospective flatmates who were so confident in their attempts to categorize us. With one short paragraph or two, we needed to build trust, find the correct length, and leave a positive memory. The pressure this task creates is overwhelming and non-ending. But, we were actively and collectively forming solidarities and making Berlin our home while we were searching for the houses that would contain our bodies and lives. The collectivity of the struggle and the humor that surrounded this practice of looking for a home in Berlin was one of the few things that made the anxiety of being without a stable place better.

‘The feeling that Berlin is full of immigrants also makes me feel like I’m not the only one in the same situation.’

The portals like ‘wg-gesucht’ are constantly building a collective memory of the housing crisis in Berlin which is steadily getting worse in the last couple of years. But after the months we spent on those websites and finally finding a flat in Berlin, what else does this experience teach us? What do we gain and lose, create and waste with all the time and effort we put into this? The main findings of the interviews showed that people from similar backgrounds or ethnicities were creating the main support systems and ‘arrival structures’ for the newcomers such as the established diaspora, old colleagues, or friends of friends. As well as more anonymous sources such as Reddit threads and Facebook, WhatsApp, or Telegram groups. These informal and mostly online practices were elements almost everyone utilized.

The last-minute changes and fast-paced nature of searching for a home in Berlin made it into a side job for most of us. We created fluid identities around requirements like a vegan diet, undying love of techno music, or open-door rules while the prospective flatmates were trying to navigate through the flood of hundreds of applications. We felt isolated, rejected, and without a community after hundreds of tries without getting any answers back while they were feeling confused, overwhelmed, and guilty. We were stuck in a type of “permanent temporariness” (Steigemann & Misselwitz, 2020) marked by uncertainty and exclusion as the outcomes of neo-liberal politics in Berlin. Maybe because we were privileged with our middle-upper class backgrounds and student identities, we all found a way to stay in Berlin. Now, when I asked ‘How do you feel about it now?’ to the interviewees, the memories of anxiety and stress faded into funny stories and anecdotes. But, even though the memories are almost always subjective, situated, and temporal, it doesn’t mean they are any less valuable.

‘Having some friends here and knowing the language helped me. Since I lived in Germany before, I already knew small stuff like the labels and brands of my favorite yogurt or toothpaste. Little things that make you feel at home.’

The temporalities of making a home in Berlin heavily affect our engagement in our daily practices and perception of the city. Our experiences as immigrants in a new country and city rely on our routines and daily life creating a ‘practical consciousness’ (Giddens, 1991). The findings reveal that the dynamic character of home-making and sense of belonging is also unilinear and temporal. Language and social citizenship are indicators of the more structural aspects of belonging with attention to individuality and ethnic backgrounds. However, an immigrant’s incapability to exercise their agency in everyday social practices results in a lack of self-confidence and a sense of disappointment. Despite these feelings, we actively make a home in Berlin while establishing relations and seeking security, control, and continuity.

‘I think it helps to be a student because you have the back of a whole university, so it’s easy to accredit why you migrated here. It is also very helpful to speak the language because they don’t notice you are new in town and act friendlier at the public offices. On the other hand, you are able to apply for social housing or any contract directly in your name.’

The initial struggles of migration make us focus almost entirely on finding an apartment and livelihood more than the socio-cultural relations we need to build to call somewhere home. However, through the struggles with our agencies, practices, and solidarities; many of us already started calling Berlin our new home. As an urban designer and architect from Turkey, the ghost stories of squatting movements and migrant struggles in Berlin were hanging at the back of my brain during these last months. Although Germany prides itself in free education and Berlin is known to be a hub for internationals from all over the world, it may soon only be open to a select and wealthy few, and the diasporic roots, solidarity groups, and the movements against the housing crisis may not be enough to make Berlin our new home.

Bibliography

Boccagni, P. (2017). Migration and the Search for Home: Mapping Domestic Space in Migrants’ Everyday Lives. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58802-9

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford University Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.de/books?id=Jujn_YrD6DsC

Hamann, U. & Türkmen, C. (2020) Communities of struggle: the making of a protest movement around housing, migration and racism beyond identity politics in Berlin, Territory, Politics, Governance, 8:4, 515-531, DOI: 10.1080/21622671.2020.1719191

Smith, E. (2022) Student Experiences of Berlin’s Housing Crisis, https://berlinspectator.com/2022/05/15/erica-smith-student-experiences-of-berlins-housing-crisis/

Steigemann, A. & Misselwitz, P. (2020) . Architectures of asylum: Making home in a state of permanent temporariness. Current Sociology, Special Issue: Researching Home: Choices, Challenges, Opportunities, pp. 628-650.

About the author

İnci graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Izmir Institute of Technology in Turkey. She studied at the University of Ferrara and Hochschule Koblenz as an exchange student. She later assumed a research position at the Architecture and Urbanism Research Academy Istanbul where she focused on engaging with different bodies and ways of living together with urban animals through informal design practices. She is resuming her studies in the Urban Design Master program at TU Berlin while taking part in several local and student initiatives such as Nesin İstasyon in Izmir and ifa_diaspora in Berlin.

Nadja-Christina Schneider

Uday Berry’s nearly eleven-minute animated short film Bharat Minar. The Tower of a Forgotten India (2019) won the Best Fiction Short category at the 2021 Architectural Film Festival in London. The film festival “showcases the cross-pollination of architecture and filmmaking, exploring the evolving scope of each discipline”. Berry is a trained architect and graduated from the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL) in 2019, where he was part of a project group (PG24) of architectural storytellers, led by Penelope Haralambidou and Michael Tite, which uses “film, animation, VR/AR and physical modelling techniques to explore architecture’s relationship with time” (Haralambidou & Tite 2023: 474).

Still from the film „Bharat Minar – The Tower of a Forgotten India“ (2019)

In his film, Uday Berry uses the exciting possibilities of architectural storytelling in his chosen format of an animated fictional short film to reflect on these complex questions and link them to different conceptions of historical time. The narrative construction and fascinating artistic realisation show the potential of visual architectural storytelling as an emerging form that will hopefully continue to thrive in the coming years and gain much more interest.

Der Wissenschaftsrat forderte vor kurzem den Ausbau der Geschlechterforschung als Fächer übergreifendes Forschungsfeld. In ihrer jüngsten Tagesspiegel-Kolumne vom 14.08.2023 nimmt HU-Professorin Jule Specht darauf Bezug und betont die wichtige Rolle Berlins für die Entwicklung der Gender Studies in Deutschland.

Gleichzeit fehle es auch hier weiterhin häufig an „langfristiger institutioneller Verankerung, wenn zum Beispiel bestehende Gender Studies-Professuren zugunsten anderer Fächerschwerpunkte abgeschafft werden, anstatt – wie vom Wissenschaftsrat angeregt – die Zahl der Professuren in diesem Bereich auszubauen“, wie Specht es formuliert.

Sie erwähnt zugleich die bedeutsame Rolle der Gender Studies für eine (selbst-)kritische Auseinandersetzung mit geschlechtsspezifischen Ungleichheiten im Wissenschaftsystem.

In wenigen Sätzen bringt die Autorin zentrale Aspekte sehr treffend auf den Punkt.

Wie steht es aktuell um die institutionelle Verankerung der Gender Studies in den Global & Area Studies an der HU? Wird das von Jule Specht hervorgehobene Potenzial einer kritischen Genderperspektive auch für diese Fächer erkannt – oder wäre jetzt ein hervorragender Zeitpunkt, um sich als Universität für deren Stärkung einzusetzen?

Mehr Hintergrundinformationen zur aktuellen Situation des GAMS-Bereichs und der im Februar 2024 endenden Gender Media Studies-Professur finden Sie in der aktuellen GAMSzine-Ausgabe: https://www2.hu-berlin.de/gamszine/

Documentary film screening and panel discussion with director Sohel Rahman and human rights activist Nickey Diamond

Organised by RePLITO/GAMS in collaboration with Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, 23.06.2023.

Fritzi-Marie Titzmann

Sohel Rahman’s feature-length documentary „The Ice Cream Sellers“ („75“) tells the story of two young siblings and the survivors of the Rohingya genocide who fled Myanmar for Bangladesh. Amidst trauma and an uncertain future, the film’s two young protagonists, brother and sister, began their new lives with hard work: selling cheap ice cream door-to-door in the world’s largest refugee camp in a desperate attempt to earn enough money to bribe officials for their father’s release from prison in Myanmar. Their seemingly endless journey through the winding alleys of the camp is interspersed with brief encounters with other residents who give the filmmaker glimpses into their stories, with interludes of children playing or people observing their daily tasks. The colourful ice lollies are a beautiful symbol of moments of joy and pleasure in the midst of this devastating human tragedy.

Shot with a handheld camera, the film invites the viewer to become part of the children’s journey through the refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, just as the director himself was invited and given intimate access to their life journey.

The well-attended screening at the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung was followed by a discussion between director Sohel Rahman and human rights activist and PhD scholar Nickey Diamond. Sohel is a filmmaker, writer and producer of Bangledeshi origin currently based in Lisbon, Portugal. His films have been screened at various international film festivals and universities around the world. He received the Best Documentary Award at the 2021 South Asian Film Festival in Montreal, Canada, and at the Tasveer South Asian Film Festival in Seattle for „The Ice Cream Sellers“, which he shot, edited and produced all by himself. In the audience discussion, he shared how intensive research and a long process of building trust eventually led to this film. Sohel approaches filmmaking from both an artistic and humanitarian perspective, incorporating his knowledge of literature, anthropology and life experiences.

He also announced a follow-up film he is currently working on, in which he revisits the camp.

Nickey added background on the current socio-political scenario in Myanmar, which has changed with the military coup of 2021. With the increasing atrocities now spreading from the discriminated minorities to the majority Burmese population, he hoped for more empathy and solidarity with the Rohingya and other minorities. Several questions from the audience addressed the question of how films can make a difference and a lively discussion developed about the international visibility of humanitarian crises and ways to show solidarity.

Anna Lena Menne, Makēda Gershenson & Alissa Steer

Have you ever genuinely stopped to consider how Information and Communication Technology (ICT) affects your life quality? While ICT, such as smartphones and the internet, are omnipresent in our daily routines, many of us fail to truly comprehend their impact on our social reality. As such, ICT remains an enigma or a so-called “black box” to many. However, the reality is that ICTs are not impartial entities. They are products of powerful individuals who bring their own values and biases to their creation and therefore perpetuate social inequality and reinforce historical structures, such as colonial dependencies. As a result, socially privileged individuals tend to reap more benefits from digitization, while marginalized groups are often left at a disadvantage. To make matters worse, personalized tech devices and content are tailored to individual preferences, but the power dynamics within the networked systems that govern other devices remain hidden. Altogether, these issues pose a universal challenge – how can we all freely and safely navigate the digital world with self-determination?

Digital Positionality and Epistemic Justice in the Digital Age

The digital age is rife with inequalities that hinder our ability to achieve true emancipation. Epistemic inequality, which manifests as knowledge gaps between individuals and between ICT creators and regular netizens, only exacerbates this issue. Our research tutorial is an innovative solution to address these knowledge gaps head-on. X-Tutorials are a type of research tutorial facilitated by the Berlin University Alliance, led by students for students, that provide an opportunity to experiment, develop, analyze, research, or evaluate self-organized projects with other like-minded individuals. Our group, linked to the department of Gender and Media Studies for the South Asian Region (GAMS) at the Institute for Asian and African Studies (IAAW) at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, is committed to promoting epistemic justice, a goal that we aim to achieve by introducing the concept of digital positionality.

Digital Positionality refers to the unique online environments of individual users and how they impact life opportunities. When engaging with ICT, our social identity and position shape the challenges and opportunities we face as we navigate our lives in a digital age. The ultimate objective of our research tutorial is to affect change at both the individual and systemic levels by designing a tool that empowers individuals to reflect on their digital positionality. This way, we hope to transform our digital experiences and those of others, fostering a more just and equitable digital world.

From Accessibility to Empowerment: Action, Collaboration, and Student Research

When it came to designing our tool, we knew that we could not simply impose our own ideas on others. Instead, we needed to gain a deeper understanding of people’s diverse digital experiences to create design principles that would be truly effective. To do this, we asked ourselves a crucial question: how can we make the concept of digital positionality accessible and meaningful to netizens, who often encounter complex technological structures through highly individualized interfaces and are sometimes misled by myths surrounding technology’s rationality? This was the key challenge we tackled in our project, inspired by a Participatory Action Learning and Action Research (PALAR) approach emphasizing collaboration and critical thinking.

Our journey began in the winter semester of 2022 at the IAAW Institute and will continue into the current summer semester of 2023. In an action learning group comprised of diverse student netizens, we sought to address the research problem that directly affects us in order to improve the digital experiences of ourselves and others. Rather than presuming to know what is best, we approached the project with open minds and in adherence to the design justice network principles, we prioritized listening to and understanding individual experiences. PALAR differs from traditional research approaches, which emphasize validity and reliability. Instead, we measure our research quality by the transformative effect of the project and consider all interactions towards achieving the project goal as data. These interactions include group meetings, field discussions, participatory strategies, and reflective journals kept by group members, all of which aim to ensure ethical conduct and personal transformation. By using this approach, we aspire to design a tool that truly reflects the needs and experiences of diverse people.

In October 2022, we initiated a cyclical action research process. Our work started with exploring the theoretical foundations of digital positionality and then examining and reflecting on our own experiences with ICT and digital positionality. To better understand the experiences of individuals from diverse and often underrepresented backgrounds, we developed research methods that were inclusive and responsive to their needs. Although our project was limited in scope due to the constraints of our university course, we evaluate its success based on the principles of PALAR. In other words, we measure the extent to which our work has empowered us as student researchers, the individuals with whom we have interacted throughout the research process, and ultimately the success of the tool we plan to create in the summer semester.

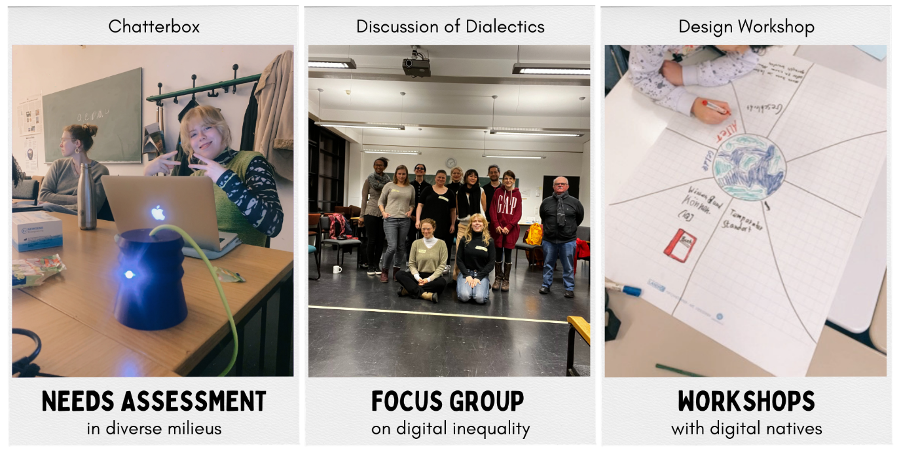

Fieldwork: Exploring Diverse Digital Positionalities

We embarked on an extensive fieldwork phase in January 2023. Our first method of inquiry was the Chatterbox, an electronic can phone developed by the Design Research Lab in Berlin, which enabled us to digitally gather and process ideas, questions, and comments on the digital sphere. With the help of a computer voice named Hans, our correspondent of the digital sphere, we interviewed approximately 60 individuals from various social milieus around Berlin, including a university and a workplace for people with disabilities, to assess their needs in reflecting on their digital positionality. We then conducted a focus group discussion with seven individuals from diverse positions in the social hierarchy, ranging in age from 24 to 72, with different identities, physical and mental abilities, and social classes, using a combination of spectrum and open-ended questions to explore issues of digital inequality and identify similarities and differences in their digital positionalities. Lastly, we organized two creative workshops for digital natives aged 11 to 14 at a community school in Berlin, teaching them about ICT and providing them with a space to reflect on their own experiences in the digital world.

Berliners‘ Perceptions of the Digital World: Beyond Established Discourses

Our conversations with people in Berlin revealed that the dominant European media discourse about the digital world significantly influenced their perspectives. Their concerns reflected issues like losing face-to-face interactions, excessive reliance on technology, addiction, and cyberbullying. They also expressed apprehensions about surveillance, data privacy, and the excessive power of large corporations in the digital realm. At the same time, the positive aspects of ICT were framed in terms of efficiency and rationality. Thus, to facilitate a more nuanced understanding of people’s relationship with digital technology beyond established discourses, our project requires an interactive educational component that emphasizes both ICT’s positive and negative aspects. Additionally, we envision the tool as open-source and easily accessible, emphasizing personal reflection and self-awareness and providing users with independent guidance to navigate the reflective process.

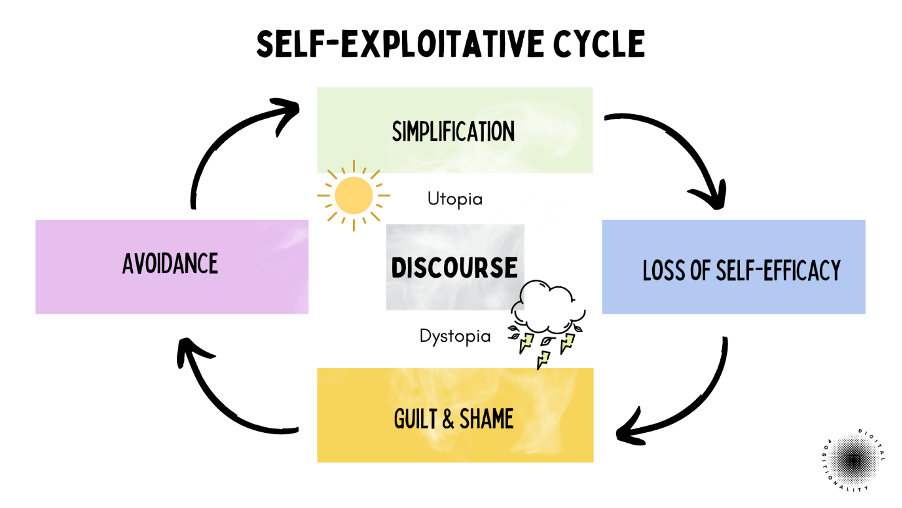

Avoiding Self-Reflection: The Cycle of Technology Use and Shame

People are heavily reliant on ICT, and they consider it a vital aspect of their daily lives. However, they tend to view technology’s benefits in terms of simplicity, convenience, or even laziness, rather than reflecting on how it enhances their quality of life. Although the European discourse agenda has raised awareness about the negative effects of ICT, most people continue to use it without engaging in genuine critical reflection. This, as we observed, leads to feelings of guilt and a perceived loss of self-efficacy among participants. During our focus group discussion, individuals acknowledged their high dependence on ICT with a negative connotation but were hesitant to delve into why. Instead, many devised rationalizations for their behavior, thereby bypassing self-reflection. This cycle of avoidance perpetuates the passive use and development of technology without addressing its adverse effects.

Some common ways that Berlin participants avoided reflecting on their ICT use and alleviated guilt and shame: acknowledging their dependence, but feeling too entrenched in it to break free, downplaying the negative aspects of technology, finding comfort in hearing that others share similar experiences, and even experiencing withdrawal symptoms when separated from their devices. There are numerous issues with this behavior of ours, but to highlight the most straightforward one: humans are the creators of technology, which means we have the ability to shape it to benefit us rather than just accepting the negative consequences as unavoidable. Taking the cycle displayed above one step further, we could compare it to psychological patterns of addiction. To address these issues, our tool must provide a reflective journey that is fun, creative, and affectively, emotionally, and behaviorally engaging. It should also help individuals identify self-exploitative dynamics and offer ways to maintain and heal throughout this reflective transformation while encouraging personalized self-assessment through shared socio-digital experiences.

The Transformative Potential of Shared Digital Experiences

The importance of shared experiences in our highly personalized digital world was a crucial factor in unlocking the transformative potential of our research project. Our primary goal was to gauge the effectiveness of our research by measuring the transformation of both our research group and the individuals we engaged with. We found ourselves and our participants expressing their gratitude, feeling empowered, and sharing their insights with their social networks as a result of engaging with our research, which was one of our greatest successes so far. Our focus group discussion further emphasized the importance of acknowledging the digital experiences of others, as demonstrated by a participant who found voice control on their phone annoying but recognized its significance for a blind person:

“For them (points to a blind person), it’s natural that voice control is better than for me. I’m currently struggling to… how can I explain it… understand these different perspectives. What is very annoying for me is important for others.” Therefore, our tool should promote engagement with various perspectives. It should also encourage sustainable digital self-determination by fostering creativity and providing resources for individual and collective societal transformation in the digital age. Most importantly, it should remain open to new ideas and continuously evolve through user input.

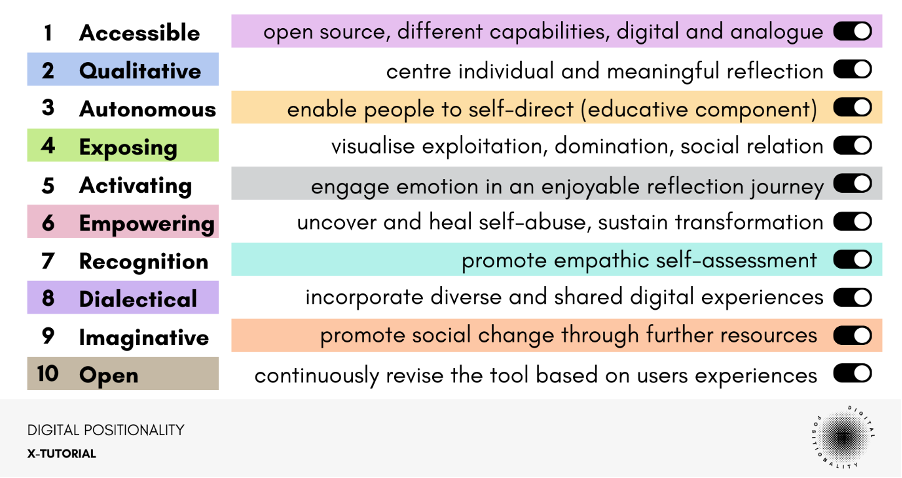

Fostering Sustainable Digital Self-Determination: Ten Principles for a Reflexivity Tool

Going forward, we will focus on these ten principles in the final X-Tutorial semester at Humboldt University to create a reflexivity tool that will support our pursuit of epistemic justice and contribute to important conversations about ethics and social justice in the digital age. If you have any inquiries, want to join us or wish to contact us for another reason, please feel free to reach out.

About the authors:

Anna Lena Menne is a Master’s student at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, where she tutors and co-researches digital positionality. Her critical research explores global transformation processes, focusing on digitization and the historical context of information societies’ epistemology/ontology and contemporary configurations of domination, order, and inequality. She completed her Bachelors’ in Media and Communications from Freie Universität Berlin and spent a partner semester at the University of Pretoria and Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. Contact

Makēda Gershenson is a co-researcher of digital positionality. She is a Master’s candidate in the Futures Research program at Freie Universität. She holds Bachelor’s degrees in Psychology and German Studies as well as a Master’s degree in Education from Stanford University, in addition to an Executive MBA from Quantic School of Technology. Her work focuses on emotional intelligence, equity and community-based interventions, bringing contemplative practices into educational settings. She trains school leaders, educators and organizations in social-emotional learning and mindfulness and supports individuals as a digital behavioral coach. Contact

Alissa Steer is a co-researcher of digital positionality. She is doing her master’s degree in Media and Political Communication at Freie Universität Berlin. Her research focuses on critical theory, platforms, and hegemony. She is a student assistant in the research group Politics of Digitalization at the Berlin Social Science Center. Here, she combines her experience from her Bachelor’s degree in Media Research from Technische Universität Dresden and a semester at Universitat Abat Olibat Barcelona with her research interest in the impact of patriarchy, imperialism and capitalism in the digital age. Contact