By Theresa Sophia Spreckelsen

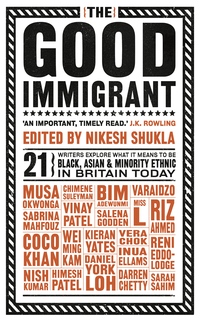

The Good Immigrant Book Cover

The Good Immigrant (2016) is an anthology of twenty-one essays by so-called British Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (“BAME”) writers who work in the literary field or the media. The essays are a stark criticism of British society regarding issues like migration, racism and cultural appropriation. These are sometimes intertwined with gender issues, for example discussing the fetishisation of “the Asian woman” and the missing representation of black hair – an identity marker for black (British) women – in popular culture. Ranging from moving to funny, most contributions combine autobiographical elements with political activism. The Good Immigrant draws attention to issues unseen by white British society but part of everyday life for non-white minorities. Published through the crowdfunding publisher Unbound, this anthology is a representative work for people who are usually marginalized and portrayed rather stereotypically. With this particular way of publishing, the audience is involved in the decision-making about works they want to read and fund the books they deem valuable. The Good Immigrant reached its funding goal in just three days in December 2015 after J.K. Rowling tweeted about it.

The term “BAME” originated in anti-racist movements of the 1970s, when people from different ethnic minorities united under the term black to fight against discrimination. In the 1990s, discussions about the universalisation of blackness, which this term denotes, emerged. It was amended to “BME/BAME” and this term has grown in frequency during the last fifteen years. While its origins are in the anti-racist movement, it is now often used by politicians and authorities to categorise citizens for census purposes among others. Recently, the term “BAME” has come under scrutiny by people who would fall under this category. It is a problematic labelling of people and separating out Black and Asian from other minorities suggests that they are either not minorities or that they are special groups that need to be regarded differently. It has been suggested to use just ethnic minorities instead. This would in turn homogenise experiences of individuals by offering them just one category of identification. Another, in my opinion more helpful, way of referring to non-white minorities is the adoption of the “system” employed in the US. [ii] People could then refer to themselves as Black British, Indian British, or change the order according to what they want to emphasise. This would mean the inclusion of peoples’ heritage, which is highly significant for the construction of identity, as well as the country where they were born, offering a more differentiated representation. Interestingly then, the term “BAME” is used on the website of the publishing company of The Good Immigrant and by its editor to refer to the authors of this publication. The important question here is, if the writers themselves identify as “BAME” or if this category is ascribed to them from the outside. From the content of the collection, one can assume that they argue for more differentiated representation than the categorisation into three possible groups. Using a controversial term to describe this group of authors almost seems hypocritical. Then, the book should not be marketed according to this category, because it is “easier” – it is also simplifying.

Nikesh Shukla, the editor of this collection, has published three novels: Coconut Unlimited (2010), Meatspace (2014) and The One Who Wrote Destiny (2018). His works have been awarded, short- and longlisted for several literary prizes. Shukla is an advocate for more diversity in the British literary field and the editor of the literary journal The Good Journal. In 2019, a version of The Good Immigrant focusing on the situation in the United States will be published. In collaboration with the writer Sunny Singh, Nikesh Shukla has started the Jhalak Prize, an annual literary prize for the book of the year by a “BAME” writer. It is the first British literary prize that accepts entries exclusively by British authors of colour.

The title of the collection, The Good Immigrant, fittingly captures the limited forms of representation of immigrants available in the media and society: they are either “bad”, stealing jobs, living on benefits and “polluting” British national culture, or “good” immigrants, working hard and assimilating to mainstream society. This and other issues are addressed in different ways in the essays of this anthology. They are connected by a common thread but at the same time refreshingly distinct from one another: even though the essays deal with the same overarching topic, The Good Immigrant does not become repetitive or monotonous.

Nikesh Shukla

Nikesh Shukla’s essay “Namaste” in The Good Immigrant is movingly addressed to his daughter, who “need[s] to know this. Because of [her] skin tone, people will ask [her] where [she’s] from.” People will treat her as if she does not belong. By explaining the meaning of the word “Namaste,” Shukla effectively shows how the unreflective use of words and phrases from other languages can be damaging. He recounts many instances where language and culture are misappropriated: in “Indian” restaurants, owned by white people who use words to describe food because they sound “Indian” and people in hippie-hipster yoga studios/bars/nightclubs (all these refer to the same place) wearing saris, saying “om” and “namaste”. Thus, the author shows how people casually and indifferently strip words of their meaning. Allegations of cultural (mis)appropriation have grown increasingly common in recent years, challenging people from majority cultures who ignorantly adopt customs of minority cultures. It is a common topic discussed in the (social) media and, like this essay, shows how people rob cultural practices and languages of their meaning. Shukla also addresses the difficulty of constructing ones’ identity in a country where he is always seen as “the other.” He uses language forcefully to recreate his own identity by using all of his three voices: “I talk Guj-lish [(a mix between his Gujarati heritage and English)], my normal voice and white literary party.”

Chimene Suleyman

Chimene Suleyman’s “My Name Is My Name,” traces the origin of her name and emphasised the meaning it has for her identity. This is one of the essays which make the (white) reader feel most uncomfortable. But it is a good uncomfortable – it is necessary. She argues, “words, names, and their noises are careless in England.” She further asks, how white men and women cannot understand that immigrants carry the burdens of their ancestors and exclaims her disbelief that “they do not carry the indignity of their ancestors […].” Thus, without directly accusing anyone, Suleyman effectually motivates the reader to engage with her cultural heritage and more importantly, with their own.

Riz Ahmed

In his amusing contribution “Airports and Auditions,” Riz Ahmed literally compares the environment of actors’ auditions with interrogation rooms at airports for people of colour. He emphasises the performativity of his identity due to the labels but on him by society, especially at the “post 9/11” airport. It is an ironic comment on the stereotyping of migrants of any generation. At the airport, “the holding pen was filled with 20 slight variations of [his] face.” This effectively shows that “[y]ou are a signifier before you are a person.” This essay humorously draws attention to the very real and very serious problem of racial stigmas that are constantly being recreated in the media.

Musa Okwanga

This burden of stigmatization is a predominant theme in most of the contributions to The Good Immigrant. In Musa Okwanga’s essay “The Ungrateful Country,” the author addresses the recent flare of anti-immigration discourse in the UK. It highlights the burden of trying of be a “good” immigrant, because maybe if you are good enough, you can change the perception of an entire nation. But no matter how hard he tries and works, the narrator constantly fears “that someone like me would never be good enough.” In relation to the current political situation in the country, this essay shows how second or third generation immigrants are often treated as guests in their own country, being constantly reminded that they do not belong. Their “social acceptance [is] only conditional upon [their] very best behaviour.”

The essays in this collection are an important read in the political and cultural climate of the day, not just, but particularly in Great Britain. By simultaneously being deeply personal and political, they inspire the reader to be more self-reflexive and further an understanding for the situations and stigmatization faced by people of colour. Even though the writers mostly stick to descriptions of the ills in society, I use the term political here, because of the effect this kind of writing can have. The writers make use of the political impact art can have, trying to achieve change in society. Even just the publication of this work and how it has come to be can be argued to be political to a certain degree, because it goes against the hegemony in the cultural field. These essays are about being the exception of the good immigrant that reinforces the perception, that the others are mostly “bad.” The Good Immigrant relates the ways in which first, second and third (+) generation immigrants, their cultures and languages are constantly being (mis)represented by the hegemonic white society.

The Good Immigrant by Nikesh Shukla, 2016

272 p.

8,99€

ISBN: 978-1783523955

[i] Shukla, Nikesh. “Editor’s Note.” In: Shukla, Nikesh (ed.) The Good Immigrant. Unbound: 2017. N.pag.

[ii] Sandhu, Rajdeep. “Should BAME be ditched as a term for black, Asian and minority ethnic people?” BBC News, 17 May 2018. Access under: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-43831279

Theresa Sophia Spreckelsen has a Bachelor’s degree in English/American Literary and Cultural Studies and Cultural/Social Anthropology from Münster University. She is currently pursuing her MA in British Studies at Humboldt-Universität Berlin. Her research interests include literary and cultural studies, politics, mental health, gender and media studies, adaptation studies and popular culture.