by Jingjing Feng, Pamela Gutierrez and Zuzanna Tarka

As a third project in the research-oriented MA course „Multi-local families in times of increased geographical and communicative mobility“ (summer term 2020), we present Jingjing Feng’s, Pamela Gutierrez’s and Zuzanna Tarka’s visual essay Comparative analysis of 3 documentaries reflecting on multi-local practices in 3 different cultures.

As people across the world people continue to migrate regionally and transnationally, more families find themselves searching for ways to “do family” from a distance. The benefits of migration are plentiful and for many include better financial opportunities and increased safety but often come at a steep cost (Kaur and Shruti, 2016; Faist, 2010). Multi-local families face daily logistical and emotional challenges that transcend nationality and culture despite the unique circumstances across the globe (Schrier, 2016). We chose to explore these cross-cultural challenges by analysing three short documentaries focusing on the countries and regions we identify with—Poland, China, and Latin America/ USA. We looked at “Violetta: Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London”, “Year of the Dog: Inside the World’s Largest Human Migration,” which focuses on a couple migrating from a village in rural China into the city, and “Immigrant Voices of America: Esther Alvarado,” which explores a Mexican woman’s story of migration into the United States. Each offered us a unique perspective into the lives of multi-local families and how they rose to the challenge of “doing family” in circumstances that are quickly becoming more common throughout the world.

- Violetta – Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London (2012)

Still from the documentary film “Violetta – Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London” by Rabikowska, M. & Hawkins, M. (2012).

In this documentary we are shown the life of a Polish women in her mid-forties, an immigrant, who left the country for economic reasons. She has debts to repay back home and knows she can make a better living in the UK. In deciding to do that, her family needs to split – her daughter stays with her ex-husband, while her grown-up son goes with her to the UK to work. Despite having her son and some semblance of family in her new country of residence, the struggles of a multi-local family persist. When she talks about her daughter back home, she says “I miss Natalia terribly, despite everything. She is a girl, and it is different with a boy”. At home she says the two had a good relationship and could talk about anything, but that closeness is difficult to maintain from afar.

The familial dynamic with her son and partner also changed when they moved to London as they traded their family home for a shared, workers household. In the house, several multi-generational families live together under one roof and share common areas, as well as spend their free time together. The importance of family ties evolves for Violetta as she embraces her new community. Eventually they even act as a sort of substitute for her nuclear family as they live together, work together, and even go to church together. As this relationship with her housemates grows, their lives in London and Poland begin to overlap.

Still from the documentary film “Violetta – Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London” by Rabikowska, M. & Hawkins, M. (2012).

On Easter she is seen celebrating with her housemates, phoning home together, and even switching phones to send regards to the other’s family members. Digital media and mobile devices play an important role in their multi-local family practices (Robertson et al., 2016; Schroeder, Ling, 2013). Occasionally, she and her friends and families visit each other back and forth between London and Poland. They all pay a lot of attention to keeping up the traditions, staying in touch with the loved ones who stayed at home and talk about their longing to go back to their country.

Her relationship with the UK is more complex and she experiences both gratitude and acceptance but sometimes also disappointment with life outside of Poland and without her family.

“It is not my second homeland, and I will never call it my homeland” says Violetta, despite living in London for years. Her immigration to London changes her sense of belonging back home in Poland but she doesn’t feel a sense of English identity either. It is touching when she says “After all, human beings are social creatures, and need someone else at all times, to love and to look after… Whether it is children, a husband, or parents, there’s always someone”. This sentiment also reflects in her frequent communication with friends and family back home and her continued longing to be with her daughter again.

2. Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration (2017)

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

In this documentary we are introduced to a couple, Yang and his wife Liu, Chinese domestic migrant workers from a small rural village in China who travel to the big city, Shenzhen, for work. Like Violetta in London, they travel far from their home to secure a better financial future for themselves and for their children back home. Living in Shenzhen allows them to support the family financially and put the children through school but also means the children are left with a grandparent back in their village. Factory workers in Shenzhen can earn up to three times more than they would back in their villages and most of it goes to their family. Yang and Liu send monthly remittances to their village, where Yang’s father is taking care of their two children, a 9-year-old boy and a 15-year-old girl (read more on importance of remittance as currency of care in multi-local family settings in Kaur and Shruti, 2016). Because of the very limited income, they are only able to visit home once a year. Digital technologies such as Wi-Fi and mobile phone signal is limited in their village which is in a very rural secluded part of the country meaning they are not able to communicate regularly with the family left at home. Their situation resembles that of many migrants worldwide, who are limited in the use of digital technologies, and therefore cannot fully benefit from the possibilities it gives to multi-local families to stay connected (Kaur and Shruti, 2016). Instead, they make one costly trip home a year to celebrate the Chinese New Year in which they try to make the most of the time they spend with family.

Before leaving Shenzhen, they go to a market to buy all sorts of gifts: nuts, sausages, snacks, new clothes – things they hardly buy for themselves on a regular day working in the city. This reflects the lives of millions of rural migrant workers in China who work hard to make the most possible money but never spend on themselves (Cai, 2003) The high cost of living and legal situation prevents them from taking the children with them to the city and the long distance puts a strain on the relationship with their young children who find it hard to reconnect with the parents after a their long absences.

To get home Yang and Liu must endure a more than 30-hour train ride in which they are lucky to even get a seat. When they finally arrive home, they are tired but excited to reunite with their family. Their 9-year-old son has been waiting anxiously to greet them from afar, but the 15-year-old daughter is less enthusiastic and doesn’t want to come out from her room. The fact that she did not grow up with her parents, let alone to build an intimate relationship with them, leaves her with a complex mix of emotions and ambiguous feelings about her parents’ return. On the one hand, she is happy that she finally sees her parents and understands that they go away to make a better life for the family, but also likely blames them for not giving her the kind of emotional love and intimacy that she has needed. Liu, her mother, is understanding. “We haven’t been there for her growing up. That is our loss”.

The left-behind children of Chinese rural migrant workers have become a hot topic for debate in recent years. Left-behind children living apart from their parents is a striking example of the changes emerging in China’s traditional family structure in the midst of economic development (Liu et al., 2000). Studies have shown that left-behind children are particularly vulnerable to exposure, to trauma and neglect and are at greater risk of developing depression (He. B et al. 2012).

3. Immigrant voices of America: Episode 1 – Esther Alvarado (2020)

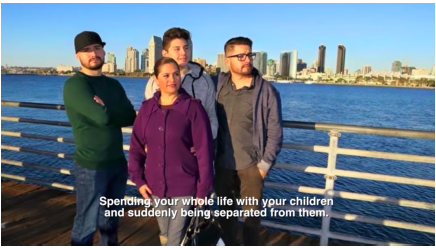

Still from the documentary film “Immigrant voices of America: Episode 1 – Esther Alvarado” by Duran, M (2020), A Start Now Studio.

The documentary tells the story of a Mexican woman, Esther, who is forced to live away from her family in the United States while her American immigration status is deliberated. Esther Alvarez, the matriarch of the family, has similar motivations for beginning the long and arduous journey into the United States as the Yang, Liu and Violetta had for their own migrations. Much like the Yang and his wife Liu, Esther’s goal was to provide for her children and “…take advantage of all the opportunities this country [the USA] provides that unfortunately we don’t have in our country.” Esther also shares in Violetta’s motherly grief, both women lamenting the long separation from their families. However, unlike the others who migrated domestically or within the then European Union, she is faced with administrative uncertainties regarding her legal status in the United States that barres her from reuniting with her family, all of which have made the US their new homeland and are anxious to welcome her back.

While separated from her family she engages in practices of “connected presence” Robertson et al., 2016, p.219) using any means to keep in touch with her loved ones: following the lives of her children and grandchildren online, watching videos and photos of them growing up, keeping in touch through phone calls, and receiving visits from her kids while she can’t enter the country. When she was forced to separate with her family for the second time, she said “it was like cutting off the wings off a bird, one second, it’s flying around an all of a sudden someone cuts off its wings.” Esther was separated from her family for seven years from 2007 to 2014. She goes through a long and humiliating process of applying for legal entry to the country despite already having lived there for many years, being married to a US resident, and having no criminal record. Her son, a Youtuber, organizes a campaign pushing for her case to be reviewed in an effort to help his mother and all families separated by harsh immigration laws. After seven years, two failed attempts and two months in an ICE detention centre she is finally granted entry to the country and reunited with her family. (Read more about ICE and why it is controversial: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/us/politics/fact-check-ice-immigration-abolish.html)

Esther endured many hardships throughout her life from being a teenage mother, to experiencing sexual assault by a smuggler during her first attempt to cross the border at 19, later getting deported, detained, and fighting for her right to a life in her adopted home. Though it all she says, “the love that I have for my children, the hope of returning to them, to be with my granddaughters, that’s what kept me going.” On February 5, 2019, Esther finally attained her U.S. Residency and she did not have to worry about being separated with her family again. It took 32 years.

Multi-local Families and Migration Across the World

Still from the documentary film “Immigrant voices of America: Episode 1 – Esther Alvarado” by Duran, M (2020), A Start Now Studio.

All the documentaries which we have seen are stories of people, who are struggling to improve their lives, while living away from their families for extended periods of time. All are recent stories and present us with the most common forms of migration in different parts of the world – Polish workers living in the UK and sending money home, Chinese families migrating from rural areas to cities while their children remain with their grandparents, and Mexican-American families being forcibly split by the immigration laws. Although we see very different life situations, reasons for their separation, and cultural background, each story connects to one another through the common themes of separation, familial bond and practices adopted to stay in touch with the loved ones at a distance.

The foundation of the multi-local family appears to be fundamentally the same across the world. Everyone hopes to live safely, to have the opportunity to prosper, and most importantly to experience the love and care of a family. Even with these similarities, families engage in unique struggles across the world. In the cases on Violetta, Yang and Liu, and Esther, they all left their homes in search of financial opportunities and to provide for their families. In Mexico and across Latin America, this motivation is sometimes followed by a need for safety, as certain areas are plagued with gang or political violence that can make migration literally a matter of life or death. Unfortunately for many, this danger is not politically recognized by those in power. For many immigrants to the United States, separation comes in pairs; first from their country of origin and later from their families and the life they’ve built in the US over many years. Deportation is a real and looming threat as immigration policy has become stricter in recent years and even those seeking asylum aren’t immediately safe from the federal enforcement agencies such as ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) or Customs and Border Protection. Multi-local families are made by literal force, not just by choice, and the ramifications are felt through multiple generations as was the case for Esther, her sons, and her granddaughters and contribute to patterns of circular migration (Hagan, J., Eschbach, K., & Rodriguez, N., 2008).

the journey home.

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

For all migrants, regardless of situation, the journey comes with a price. For Violetta this means leaving not only her family but also her native land, culture and language for a different country, devoid of the comfort and familiarity of home. She worries for her daughter and also for her country, at one point in the documentary anxiously discussing the enormous snowfall in Szczecin that knocked out electricity to the city. To paraphrase the English expression, “You can take the woman out the country, but you cannot take [Poland] out of the woman.” Our history, like our families, are a part of us all and no amount of distance can erase the love of either in Violetta’s heart and mind.

For Yang and Liu who migrate within their native China, the struggles are equal but different. They don’t need to practice a new language and can enjoy some same of the same cultural norms but are challenged by sheer size of China itself. They must travel thousands of miles to see their family by train, approximately one day and two nights, and have young children that are growing up without them. The village is small and remote and many of the digital technologies that Violetta and Esther rely on to maintain relationships with their distant families are limited or unavailable to the couple. They may remain in China but are perhaps the most cut off from their family while away working in the city.

Esther’s story, though rife with struggle, has almost the opposite problem as Yang and Liu. While in Mexico she lives just across the border from San Diego where her family lives and her son is a Youtuber adept at sharing his life with her digitally. Her close proximity to the United States both affords her visits from her sons who can cross the border into Mexico to see her but also serves to constantly taunt her with what she cannot have. She is at all times, “so close, yet so far.”

In all three documentaries there is the question of expectation versus reality for the families. Violetta has moments of both peace and conflict with her situation in London at one point frustratedly saying, “This is not how I expected it to be. This is not how it should be. I ended up in England doing a shitty job in a shitty factory…”. Multi-local families make difficult decisions when choosing to separate but the result is nearly always a gamble of sorts. Violetta comes back later in the documentary to say that her life is ultimately good in London and she doesn’t wish to immediately go back to Poland but adds, “You cannot rewind time, unfortunately. It always comes with a price.”

Liu faces similar questions when she returns to her village in China and finds that her teenage daughter is not as welcoming as she would have hoped. She briefly wonders if given the choice again she would choose to leave the village. Despite her concerns, her husband Yang knows that village life cannot provide the family with what it needs to survive. He understands that this cycle of migration will continue with his children as there is no opportunity for them at home. Perhaps one of their largest challenges is that their multi-locality as a family is likely to be permanent as the children will eventually replace their parents as migrants to the big city. Yang hopes to return to the village in his old age but by that time his children will be the ones who’ve left home in search of opportunity.

means “confidence.”

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

Violetta and her housemate, despite being comfortable in London, also dream of returning to Poland at some point. On New Year’s they gather for drinks and toast to Poland saying, “To Poland! May we go back someday when it is better.” This is perhaps one of the most striking differences between Violetta, Yang and Liu, and Esther. For Esther from Mexico, her story of migration is meant to be permanent. Her children have been raised in the US and are now raising their own children in the country. Mexico will always be a part of their family story, but their lives are now in San Diego making her separation all the more unbearable. Of migrating to the US, she says, “My objective was always to become a U.S. citizen and to continue contributing to this country, to work, excel, and give a better future to my son[s]…”

In all documentaries we see families split for long periods of time and big distances because of necessity. Whether for the economic or legal reasons, these times of absence become an important factor for how they build and sustain relationships with their kin and loved ones. Especially for parents separated from children, they face many difficulties in maintaining the high level of emotional involvement in each other’s lives (Schrier, 2016). In order to make it possible they engage in variety of different practices of connected presence (Robertson et al., 2016; Licoppe, C., 2004) – sending money home, visiting family when possible and bringing gifts for the family members (Kaur and Shruti, 2016), celebrating traditions, foods and national holidays together, as well as keeping in touch through social media, phone calls and sharing photographs (Robertson et al., 2016). People who are forced to leave their family homes and family members behind to improve their quality of life often still question their decision to leave and become melancholic when considering the possibility of going back to their homelands even while knowing that’s not possible. While taking advantage of the “the possibilities of simultaneity” (Huang et al. 2008 , p. 7), the forced separation from the families seem to be increasing the internal divide of being “neither here, nor there” (Huang et al. 2008 , p. 7).

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

Analysing multi-locality through documentaries

In addition to presenting different kinds of migration stories, the documentaries themselves use different formats to deliver their messages. The artistic form of expression chosen by the authors and creators of the documentaries can tell us a lot about way they approach the topic, their perspective and the topic itself.

“Violetta: Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London” uses a mix of observational and interview formats to tell her story. It’s the most unfiltered of the three documentaries using a fly-on-the-wall tactic through much of the filming which is later interspersed with interviews with Violetta to contextualize her situation. The title of the documentary itself – ‘a portrait’ – points out to the focus of the director on the figure of the woman, painting an intimate picture of her life, rather than focusing primarily on the aspect of immigration. Because the documentary provides little to no context of the situation in Poland or why London is a popular migration destination, Violetta is allowed to shine as the sole subject of her story. This is positive in that the viewer is allowed to concentrate on her situation as a person, not only under the term “migrant” that often carries its own associations. On the other hand, Violetta is a migrant and contextualizing her story as part of a general narrative of migration from Poland could serve to better understand the situation as a whole. Because of that we get the feeling that Violetta might have been filmed by someone close to her, who understands her life choices well and sympathises with her situation.

The second documentary produced by the big international broadcaster Vice News seems to be done from a very different angle and created with an aim to introduce the realities of the protagonists to the unfamiliar audiences. In what follows, parts of the interview, particularly with the young boy, do not feel natural to a native Chinese speaker who understands the culture. It seems that he is encouraged to answer interview questions in a “correct” way as if he is guided, which reflects another drawback of documentary films in that they always come with some subjectivity of the film maker or the interviewer. Because of this approach we feel the distance from Liu, Yang and their children, and observe their life unfolding like a movie, rather than being pushed by the director to feel how the life in their shoes might feel like. However, in being much more structured than the first documentary, ‘The Year of the Dog” gives a much better background and the overview of the situation, and presents the surrounding in the way that they become the part of the story, and we get to see the link between the protagonists and their changing environments.

Our final documentary, “Immigrant Voices of America: Esther Alvarado,” is one of an eight-part documentary series focusing on the different immigrant groups in the United States and their stories. In this way, Esther’s story is woven into a larger narrative about the immigrant experience in the United States and the various struggles they may encounter. Much like the other documentaries we watched, there is combination of observational and expository techniques as the story of Esther’s life is juxtaposed with images on the screen. However, unlike the previous two documentaries, both Esther and the filmmakers appear to be passing a value judgement on current immigration policies. The viewer is meant to finish the film with a new sense of right and wrong, having been more than just educated on her story but also the political undertones of her situation. Depending on the topic and each person’s set of values, this can be either positive or negative as the filmmakers are aiming to convince the viewer of one position over another. In addition to the filmmakers, Esther’s eldest son is a prominent Youtuber and films some of the more intimate footage himself including scenes at the hospital when Esther is undergoing cancer treatment. This close personal connection to the subject is beneficial in that the viewer feels a true sense of consent as they follow her on this very personal journey. Also because of her son’s YouTube career, the documentary incorporates previously shot footage from his channel and allows us a glimpse at Ether’s story over many years. Again, this makes for an intimate but not impartial view of Ether’s life as an immigrant, a stark contrast to Violetta, Yang and Liu’s films which primarily aim to tell as story and allow the viewer to judge or interpret their stories for themselves.

The unprecedented development of communication technology and social media in the past few decades has not only evoked limitless potential of how people maintain their relationship at distance, but also opened new possibilities of information production and sharing across the globe. Information visualization has developed at a lightning speed like never before in history during this transformation. Despite its growing influence, the use of visual data such as images, documentary films and short videos has been scarce and mostly overlooked in scientific research. (Joffe, H., 2008; Nisbet, M. & Aufderheide, P., 2009). In multi-local family study, or in migration study to a larger extent, the richness and emotive impact of visual materials’ ability to arouse emotion is undeniable (Joffe, H., 2008). In a digital era, visual records form an integral part of our cultural and social lives, and its influence will only grow in the foreseeable future. As Madianou (2016) rightfully argues, technological advancements together with affordances of social and mobile media have brought new possibilities. Hence, in spite of its subjectivity, it is argued in this article that visual data brings great value to the study of multi-locality and shall be given more attention in scientific research.

About the authors:

Pamela Gutierrez is currently enrolled in the M.A. Global Studies Programme at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin after finishing her dual B.A. in International Relations and Communication. Her research interests include forced migration, diaspora studies, social inequality, development, gender, and cross-cultural communication, particularly in the US American and Latin American contexts.

Zuzanna Tarka is currently doing her M.A. in Global Studies Programme at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin after finishing her B.A. in Sociology at the University of Glasgow. Her research interests focus on digitalization, digital economy and communication, digital divide and inequalities in access and use of new technologies, with particular focus on gender.

Jingjing Feng is a M.A. student of the Global Studies Programme at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. In her earlier studies she did her B.A. in Tourism Management at Shanghai University of International Business and Economics. Her research interests include global migration and mobility, global culture, identity and ideology, inequality and international development.