Nadja-Christina Schneider

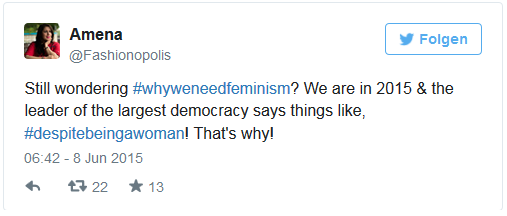

„Mahila hone ke baujud bhi“ – im Englischen mit „despite being a woman“ übersetzt – dieser selbstentlarvende Einschub in einer Rede, die der indische Premierminister Narendra Modi (BJP) Anfang Juni in Dhaka im Rahmen seines Staatsbesuchs in Bangladesch gehalten hat, sorgt seither für angeregte Diskussionen in der indischen Medienöffentlichkeit. Eigentlich wollte Modi darin das entschlossene Vorgehen von Premierministerin Sheikh Hasina im sog. Kampf gegen den Terror anerkennend hervorheben. Dies misslang ihm jedoch gründlich, denn eine unverändert patriarchale Haltung und unzeitgemäße Geschlechterstereotype sind nun die beiden ersten Assoziationen, die mit seinem denkwürdigen Auftritt in Dhaka in Verbindung gebracht werden. Unter dem Hashtag #despitebeingawoman postet seither eine stetig wachsende Zahl an Twitter-Userinnen und -usern ihre Kommentare und zahllosen Beispiele herausragender Leistungen und Errungenschaften von Frauen in Indien, aber auch satirische Inhalte und Karikaturen:

Bei der Vorstellung seines Kabinetts im vergangenen Jahr wurde der neu gewählte Premierminister teilweise noch überschwänglich von den Medien dafür gelobt, dass sich der Frauenanteil darin auf fast fünfzehn Prozent erhöht hatte und ein Viertel der Ministerposten mit Frauen besetzt worden waren. Die hindunationalistische indische Volkspartei (BJP) hatte sich generell aus wahlstrategischen Gründen in den vergangenen Jahren eine Rhetorik der Geschlechtergerechtigkeit zu eigen gemacht und vor allem im Wahlkampf 2014 eingesetzt. Insbesondere die säkular begründete indische Frauenbewegung beobachtet dies mit großem Unbehagen, denn zahlreiche Äußerungen und Handlungen von BJP-Mitgliedern sowie von anderen hindunationalistischen Organisationen im Umfeld der Partei sind nach wie vor kaum mit einem egalitären, liberalen Feminismus in Einklang zu bringen. Folglich bot Modi vielen, die an seinem überzeugten Engagement für eine gerechtere Geschlechterordnung in Indien stets gezweifelt haben, mit seiner Äußerung geradezu eine Steilvorlage, um seine patriarchale Haltung zu kritisieren und ihn mit Spott zu bedenken.

Twitter ist jedoch auch ein Medium, das Premierminister Modi selbst äußerst erfolgreich für seine strategische Kommunikation mit fast 13 Millionen Followern nutzt und so ließ die Gegen-Hashtag-Kampagne #ModiEmpowersWomen ebenfalls nicht lange auf sich warten. Viele englischsprachige Medien weltweit scheinen dennoch ausschließlich über den Hashtag #despitebeingawoman zu berichten, der vielfach als „social media storm“ bezeichnet wird, den Modi durch seine Äußerung entfacht habe.

Diese Skandalisierung und die wachsende Zahl an Berichten von Medien über das, was sich in den sozialen Medien tut, sagen auf der einen Seite viel aus über die rapide gewandelten Medienumgebungen und kommunikativen Dynamiken in der indischen Gesellschaft. Auf der anderen Seite lässt die starke Medienresonanz auf Modis Äußerung aber auch die Zentralität von genderbezogenen Themen in dieser gewandelten indischen Medienlandschaft erahnen. Es ist zwar keinesfalls neu ist, dass die Situation von Frauen, Diskussionen über Frauenrechte und Gleichberechtigung oder genderbezogene Diskriminierung ein sehr großes Interesse der indischen Medien und generell in öffentlichen Debatten allgemein erfahren, doch die Medienberichterstattung und daran anknüpfende Anschlusskommunikation hat sich zweifellos im Zuge der fortdauernden Debatte über sexuelle Gewalt seit 2012 stark verdichtet.

THE CARAVAN

By SUHIT KELKAR | 1 October 2014

LATE THIS AUGUST, the Film Forum of Manipur made a bold announcement. The state’s apex industry guild and regulatory office, which ensures that all films abide by censorship rules imposed by local separatist groups, slapped six of the regional industry’s actors with a six-month ban. The punishment was meted out for failure to support protests for an “Inner Line Permit” system in Manipur. The ILP system, which requires outsiders to get special permits to visit a state, is in force in Nagaland, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, where tribal populations see it as a protective membrane over local ways of life.

The actors, each of whom has about ten to twenty films in the pipeline, argued that they had never received a notice to attend the protests. The Film Forum’s Executive Council refused to accept the excuse. In early September, Laimayum Surjakanta Sharma, the Forum’s chairman, told me over the phone that the ban would hold, although actors were free to act in music videos. “We will see how much they support our campaigns in the near term,” Sharma said, hinting at the possibility of a commuted sentence. “We are giving them a lesson.”

– See more at: Manipur Masala

Shifting Urban Landscapes and the Politics of Spectacle

von Roos Gerritsen

Den kompletten Essay finden Sie unter:

http://www.tasveergharindia.net/cmsdesk/essay/115/index.html

In seinem Essay untersucht Gerritsen die Entwicklungen in der Stadt Chennai (im Bundesstaat Tamil Nadu). Hier geht die lokale Administration seit 2009 gegen die auswuchernde politische und ökonomische Plakatwerbung vor. Anstatt dieser Plakate und Fassadenbemalungen kann man nun an den Wänden und Häuser entlang der Hauptstraßen Kunstwerke mit Bezug auf die tamilische Kultur und Natur bestaunen. Heute gibt es an über 3.000 Stellen ein Verbot öffentlicher Werbung und immer mehr lokale Motive anstatt der nervigen politischen und ökonomischen Plakate zieren viele andere Wände in Chennai.

„As postcard images the new murals have contributed to the reinforcement of the iconic, standardized status of history, tradition, and the beauty of the State, but is not their repetition again creating indifference? I think we can be almost sure that after the newness of the mural form has worn off, the depicted scenes will return from their short-lived presence in hyperreality into the sphere of clichéd, everyday manifestations that are largely unnoticed. For the moment, the city authorities steadily continue to embellish even more public walls.“

References

Alpers, Svetlana. 1991. The Museum as a Way of Seeing. In Exhibiting cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. I. Karp and S. D Lavine, 25-32. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Anderson, Benedict. 1978. Cartoons and Monuments: The Evolution of Political Communication under the New Order. In Political Power and Communications in Indonesia, ed. Karl D. Jackson and Lucian W. Pye, 282-321. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Trans. Richard Nice. 2002nd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Brosius, Christiane. 2010. India’s Middle Class: New Forms of Urban Leisure, Consumption and Prosperity. New Delhi: Routledge.

Deshpande, Satish. 1998. Hegemonic Spatial Strategies: The Nation-Space and Hindu Communalism in Twentieth-Century India. Public Culture 10, no. 2 (1): 249-283.

Eco, Umberto. 1990. Travels in Hyperreality. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Fernandes, Leela. 2006. India’s New Middle class: Democratic Politics in an Era of Economic Reform. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

Fuller, C. J., and Haripriya Narasimhan. 2006. Information Technology Professionals and the New-Rich Middle Class in Chennai (Madras). Modern Asian Studies 41, no. 01 (12): 121.

Hancock, Mary E. 2008. The Politics of Heritage from Madras to Chennai. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ivy, Marilyn. 1988. Tradition and Difference in the Japanese Mass Media. Public Culture 1, no. 1: 21.

Jacob, Preminda. 2009. Celluloid Deities: The Visual Culture of Cinema and Politics in South India. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Jaffrelot, Christophe, and Peter van der Veer. 2008. Patterns of Middle Class Consumption in India and China. Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd.

Kusno, Abidin. 2010. The Appearances of Memory: Mnemonic Practices of Architecture and Urban Form in Indonesia. Durham: Duke University Press.

Note, Osamu. 2007. Imagining the Politics of the Senses in Public Spaces: Billboards and the construction of visuality in Chennai city. South Asian Popular Culture 5, no. 2: 129.

Pandian, M. S. S. 2005. Void and Memory: Story of a statue on Chennai Beachfront. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6: 428-431.

Ramaswamy, Sumathi. 1998. Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891-1970. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Rowlands, Michael, and Christopher Tilley. 2006. Monuments and Memorials. In Handbook of Material Culture, ed. Christopher Tilley, Webb Keane, Susanne Kochler, Michael Rowlands, and Patricia Spyer, 500-515. London: Sage Publications.

Srivastava, Sanjay. 2009. Urban Spaces, Disney-Divinity and Moral Middle Classes in Delhi. Economic & Political Weekly 44: 26–27.

Srivathsan, A. 2000. Politics, Popular Icons and Urban Space in Tamil Nadu. In Twentieth-Century Indian Sculpture: The Last Two Decades, ed. Shivaji K. Panikkar, 108-117. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Tarlo, Emma. 1996. Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Zukin, Sharon. 1995. The Cultures of Cities. Maldon, Oxford and Carlton: Wiley-Blackwell.