Alexa Altmann

An ad recently published in The Hindu for the luxury brand Kalyan Jewellers has sparked a controversy over colonialism, racism, child-labour and slave-fantasies as well as over public image projection and accountability. The depiction of movie-star Aishwarya Rai Bachchan in the fashion of a European colonial-era aristocrat, bejeweled, poised and shaded from the sun by an undernourished black child-slave, has prompted the outrage of several feminist and child rights activists as expressed in an open letter to Rai Bachchan and Kalyan Jewellers. The authors equally draw attention to the racist implications of the slave fantasy depicted in the advertisement by referencing the colonial heritage of comparable historic portraitures and to the romanticisation of child servitude. While Kalyan Jewellers promptly issued an apology and withdrew the image, Rai Bachchan’s publicist declared the final layout featuring the black child-slave was edited without the actress’ knowledge and consent and thus only the responsibility of the brand’s creative team. The activists countered by questioning this statement and Rai Bachchan’s alleged lack of control over her own public image. They demand Rai Bachchan to take a clear stand, both as an icon and in her role as UN Ambassador, against racism and the trivialization of servitude as well as take full responsibility for the commercialization of her public image projection.

Mette Gabler

Recently, a video has gone viral again. This time it is caught in a triangle of consumerism, gender and change, and set off a debate on feminism, gender equality, class and empowerment. The advertisement “My Choice” selling the magazine and brand Vogue as well as the idea of empowerment was produced as a collaboration between director Homi Adajania and Indian actor Deepika Padukone. This advertisement is part of the social awareness initiative of Vogue India, #VogueEmpower. Deepika Padukone’s voice carries the message, based on a piece written by Indian screenwriter Kersi Khambatta, and begins with the words “My body, my mind, my choice”. The black-and-white film cuts between images of female faces and bodies of 99 people of different ages, religions and belonging, including film critics, directors, and other figures of the so-called ‘glamour’ industry, as well as Deepika Padukone herself. The lines address a wide range of topics relevant in feminist discourses, from body image, gender norms, sexuality, and reproductive rights, as well as love, romance and relationships. It ends with the statement “Vogue Empower. It starts with you”, which reflects the aim of the advertisement, to “encourage people to think, talk and act in ways big or small on issues pertaining to women’s empowerment. The message is simple: It starts with you” given on Vogue’s YouTube channel alongside the video.

The intentions, content and implementation of the message are currently discussed on social media and in various forms of national and international online press. Voices include private individuals, activists, journalists, representatives of right wing politics, and film celebrities.

Vogue Empower seems to convey the idea that it is up to each individual to engage, get involved on their own account but potentially also beyond, because it might “start with you” but where does it go after that? The understanding of empowerment, in particular, is now under grave scrutiny and criticised in various ways. The debate ranges from the question which ideas are valuable to address to what empowerment can be, and if this form can at all be a vehicle for empowerment. Deepika Padukone’s own perspective on empowerment is shared on Vogue’s YouTube Channel: “I’ve always been allowed to be who I want to be. When you’re not caged, when you don’t succumb to expectation, that’s when you’re empowered.”

Although some have supported the messages and see it as a celebration of women “not in a way that society expects them to be but in way of her being an individual, a separate entity, one who can make choices of her own and live life on her own terms.” (http://www.scoopwhoop.com/inothernews/celebrating-women/) and being truly feminist (http://www.thehindu.com/trending/deepika-padukone-in-my-choice-video-of-vogue/article7056615.ece), the debates that followed strongly questioned whether empowerment conveyed in the video was relevant or useful.

Several strands of critical voices point out that the issues addressed in the video only target a privileged minority of the population in India. Accordingly, the issues of clothing, bodily integrity and authority are a matter of personal choice and therefore would not qualify as topics of female empowerment (/http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/MyChoice-Twitterati-cheer-for-Deepika/photostory/46753891.cms). This critique seems to create a division between one group of people, privileged and not in need of empowerment and another underprivileged group, who benefit from empowerment. The juxtaposition of personal choices is in many articles posed against issues of public concern such as female foeticide, abuse, access to education, domestic violence, rape, harassment at workplace, equal leadership opportunities, the pay gap, financial independence, the intrusive male gaze, and everyday sexism (http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/wanted-less-style-more-substance/article7058383.ece). In this I see a certain hierarchical setup between issues that according to these critiques are worth addressing and issues that can be dismissed as privileged luxury problems.

Some of the critical stances seem to contradict each other. One on side, the dilemma of potential dangers or repercussions as unwanted consequences of the choices made beyond what is expected and set as the norm is considered. On the other side, this campaign is regarded for its potential harm is could do to the existing feminist movements. It is seen as a appropriating of women’s rights movements and branding feminism into a slick, cool and glamorous package instead of acknowledging the hard work that goes into it. In my opinion, one kind of struggle for feminist ideals is thereby romanticised while the other is thought of as easy. While surely the activism and work done in the history of women’s movements has not only been important but also dangerous and full of hardship, making the choices addressed in the video could also be a source of struggle.

Some articles debate the messages itself as hypocritical, in more than one way. According to this point of view, the choices “sold” in this ad stem from an industry riddled with stereotypical definitions of beauty and femininity thereby only supporting one kind of choice and freedom, one that fits within the frame of these definitions. Moreover, some saw the video as sexist in that the same demands of freedom to choose sexual partners “outside of marriage”, which was by many read as promotion of adultery, bigamy, and indifference, could not be claimed by the male part of the population. All these viewpoints illustrate that the video has definitely created a debate with diverse perspectives.

The debates continues to also inspire creative media output. While for example Amul, an Indian dairy cooperative based in Gujarat known for commenting on current popular, political, social and cultural events, incorporated the debate in its campaigning, by focusing on the divided opinions, others created responses delivering their own point of view: several examples of a male version of “My Choice” (here is one arguing that the Vogue ad is sexist : http://www.ndtv.com/offbeat/beer-belly-is-my-choice-spoof-of-deepika-padukones-vogue-video-751043), a dog version, and other spoofs e.g. incorporating the images of the “My Choice” video into other advertisements to highlight the sales of products over the social message (http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/feelings/can-you-spot-the-hidden-ads-in-deepikas-mychoice-video/).

The reactions to the video must be said to be as diverse as the potential audiences, as the people voicing the critiques and reacting to the messages are all part of the audience (for another text on the critical viewpoints visit: http://kafila.org/2015/04/09/being-empowered-the-vogue-way-is-there-anything-left-to-be-said/). Each view contributes opinions, setting up a debate and potentially creates new perspectives in the feminist movement on gender equality, and what empowerment should mean. In light of this, the campaign has definitely proved successful in the goal to “encourage people to think, talk and act in ways big or small on issues pertaining to women’s empowerment”.

And I wonder, is being critical not also a sign of being privileged? There is a certain literacy that comes with the possibility of being part of the audience, first of all accessibility but also usage of a technical devices with a screen. Second, to be able to react to the issues mentioned in the short film one must not only understand the English language but also have an idea or understanding of empowerment as a concept, as well as being versed in debates on gender and the women’s rights movements. While for many the message of the “My Choice” advertisement is selling both a product and an idea, catering to a small group of people, is it not a crass assumption, that no one can be inspired by it in other ways than simply disagreeing? Sparking creativity beyond finding what is wrong with it, but potentially how it is relevant to some, affecting some part of their realities, or by simply inspiring some to get more information, and challenging some norms and expectations? Because, in the end, why is it a question of either or? And not a statement of all, everywhere, all the time? If the voices in reaction to this advertisement are diverse, why not also the possible impact? Debate being the source of movement and change.

See also: transgender-version of ‚My Choice‘

Film celebrates 50 years of Satyajit Ray’s sleuth

Perhaps few other characters in Bengali fiction stir as much feelings in the young and the old alike as Feluda, the detective personality created by Satyajit Ray. Feluda who came to life through a story in a children’s magazine in 1965, ‘turns’ 50 this year. A documentary tells his story. Text: Indrani Dutta/Suvojit Bagchi

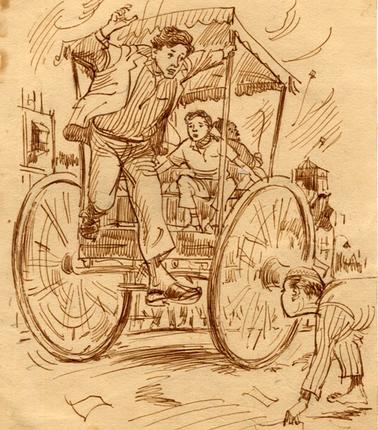

The first short story of Feluda, with sketches by Ray was published in 1965-66 in Sandesh, a children’s magazine. The maiden Feluda novella titled ’Badshahi Angti’ (The Emperor’s Ring) with more sketches by Ray appeared the same year. The magazine was launched in 1913 by Ray’s grandfather– writer, painter, printer Upendrakishore Raychowdhury. The editor’s mantle was donned later by Ray’s father, poet, illustrator and playwright, Sukumar Ray. (Courtesy: Ray Society)(Source: The Hindu, April 18)

Reader comment by Koel (The Hindu, April 20):

“Feluda – irreplaceable. I think he is the greatest tribute to the literary and intellectual middle class Bengali psyche”.

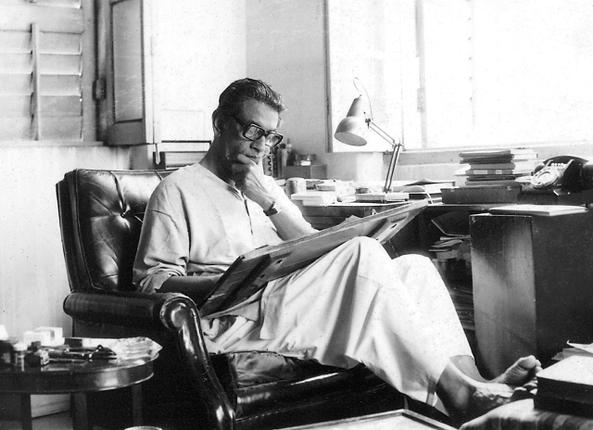

Writer and auteur, Satyajit Ray, created many of his characters sitting in this chair in central Kolkata’s Bishop Lefroy Road. One of his char-acters, Feluda, the quintessential Bengali gentleman sleuth, is com-pleting his golden jubilee later this year. (Courtesy: Ray Socie-ty)(Source: The Hindu, April 18)

Den vollständigen Artikel finden Sie auf thehindu.com

SCROLL.IN, 14 March, 2015

Mayank Jain

Inspired by a German artist, students of the University of Delhi and Jamia Millia Islamia are displaying feminist messages on sanitary napkins.

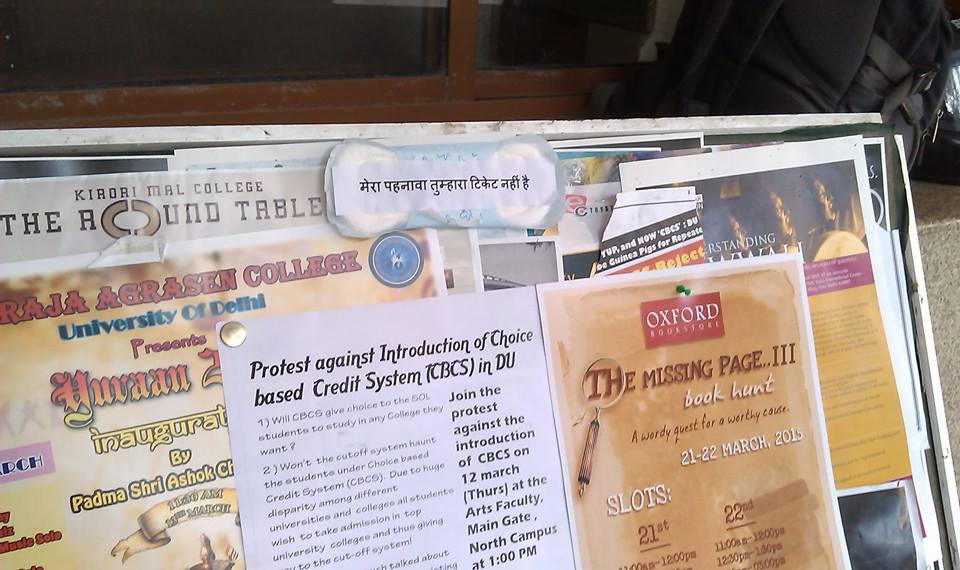

Sanitary napkin sales have been shooting up around colleges in Delhi, thanks to a public art project inspired by German artist Elone. On International Women’s Day on March 8, Elone scribbled feminist messages on sanitary pads and put them up all over Karlsruhe city. Students of various colleges in Delhi have taken up the challenge, and have covered campus walls and trees with statements on gender equality.

An image from Elone’s campaign.

Students of the Jamia Millia Islamia university made the first move on March 12. “We were really impressed with what happened in Germany and decided to do the same thing on our campus,” said a student activist on the condition of anonymity. The campaign hopes to bust taboos about menstruation and target the larger culture of misogyny. The messages include ‘Streets of Delhi belong to women too’, ‘Rapists rape people, not outfits’, and ‘Period blood is not impure, your thoughts are’.

“It’s not just students ‒ educated people, including teachers, tend to view menstruation as something unnatural and despicable,” the activist said. “We want to send a message that sexism cannot and will not be tolerated.”

Easier said than done. Jamia officials took down the pads, which were put up by the students without permission. The students are undeterred, and took the campaign outside the campus and onto the streets of Delhi. “We expected some opposition but this was a shock,” said another student, who had spent a whole day putting up the pads, on the condition of anonymity. “We are going to take the message forward to the city until the hostility ends.”

Meanwhile on Friday, a group of students from the University of Delhi showed their solidarity by putting up similar revolutionary pads across the North Campus area. “We simply want people to understand that menstruation is not a crime and a girl should not be victimised for something so natural,” said Rafiul Alom Rahman, who initiated the campaign at DU. “We put feminist messages on the pads even though we knew that people will not be okay with seeing sanitary pads with red paint.”

DU officials, and possibly some students, also did not approve of the campaign. Some of the pads were found to be torn, while others were pulled off trees. “A security guard pulled a pad out of his pocket and asked me to put it somewhere else,” Rahman said. “We are not going to be cowed down. We are thinking of ways to make this campaign even bigger and involve other universities and students.”

Here are some photographs of the public art campaign from social media.

Read more at: Why are sanitary pads with little notes stuck on trees and walls of Delhi colleges?

You’re a ‘bad girl’ if you fight rapists or go out with boys: New Meme

You’re a ‘bad girl’ if you fight rapists or go out with boys: New Meme

By: Meghna Malik, The Indian Express

Barely a month after the first ‘bad girl’ meme went viral on the internet, another ‘bad girl’ chart is doing the rounds on social media. The chart comes shortly after Leslee Udwin’s controversial documentary, ‘India’s Daughter’, which is based on the rape and murder of a 23-year-old student in December 2012. This documentary has been banned by the government of India.

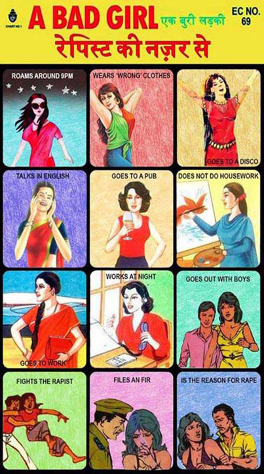

Titled ‘Ek Buri Ladki – Rapist Ki Nazar se‘, this satirical chart shows 12 illustrations that depict the qualities of a bad girl, according to a rapist. Going by the chart, in the eyes of a rapist, a girl is a ‘bad girl’ if she roams around after 9 PM, fights the rapist or goes out with boys.

The chart further reads that a girl who talks in English, goes to a pub or files an FIR against the rapist is also a bad girl.

Quelle: http://indianexpress.com/article/trending/youre-a-bad-girl-if-you-fight-rapists-or-go-out-with-boys-new-meme/

Eine größere Version des Posters kann hier angesehen werden: bad-girl31

Sanjay Hegde (The Hindu, March 10, 2015)

For the past one week, we have been told that the documentary India’s Daughter has been banned. The truth, however, is different. The perusal of three documents involving official communication in the matter show that what has been temporarily restrained until further orders is the telecasting of an interview recorded with Mukesh Singh

On International Women’s Day, March 8, the news channel NDTV went blank with only a visual of a lamp, the words ‘India’s Daughters’ and a scroll running beneath it putting out statements issued by the Editors Guild of India and others. It reminded me of the blank editorial column in the Indian Express published on June 28, 1975. This page protested the censorship that was imposed following the promulgation of Emergency. The same week, the obituary column in the Times of India carried this entry: “D’Ocracy D.E.M, beloved husband of T. Ruth, loving father of L.I. Bertie, brother of Faith, Hope and Justice, expired on June 26.”

Emergency-era stories, of protesting censorship within the confines of the law need to be retold to a young India born since those dark days so that the message of the current protest acquires greater context and resonance. For the past one week, angry anchors, outraged politicians and the raucous discourse of public life have informed us that the documentary India’s Daughter has been banned. However, the truth is different. The documentary has not been banned. Yes, you read that right. What has been temporarily restrained until further orders is the showing of an interview recorded with the convict Mukesh Singh. This is the sequence of events.

Der vollständige Artikel aus The Hindu kann hier gelesen werden.

Sanjay Hegde ist Anwalt am Supreme Court in Delhi.

Unmittelbar vor dem internationalen Frauentag am 8. März ist die Debatte über das verhängte Sendeverbot gegen die BBC-Dokumentation „India’s Daughter“ (Regie: Leslee Udwin) weiterhin ein dominantes Thema in den indischen Medien. Die vielfach kritisierte Zensur hat die Debatte über sexuelle Gewalt neu belebt. Standen in der vergangenen Woche noch die Absurdität von Filmzensuren im Zeitalter digitaler sozialer Medien sowie die Äußerungen eines der angeklagten Täter im „Nirbhaya Gang Rape Case“ (zu diesem Thema: 2012 Delhi Gang Rape Case) im Vordergrund, so richtet sich der Fokus der Diskussion und Kritik nun verstärkt auf zwei Verteidiger, die im Film ebenfalls zu Wort kommen. Ihre Äußerungen haben die indische Anwaltskammer dazu veranlasst, sog. Show Case Notices zu erlassen, also Aufforderungen an die beiden Anwälte, die Beweggründe für ihr Verhalten darzulegen (zu diesem Thema: Show Cause Notice to Lawyers of Nirbhaya Case Accused).

Für den Indian Express kommentierte die indische Politikerin und Frauenrechtsaktivistin Brinda Karat die aktuelle Debatte in Indien:

FACE THE TRUTH

Written by Brinda Karat | Published on:March 6, 2015 12:00 am

India’s Daughter, the government need not be oversensitive about it.

The government repeated a charge made by a woman MP from the ruling party that this would “affect tourism”. This is rather like saying, save India’s reputation, not its women. It is sickening that the government should be concerned more about the loss of revenue and image rather than taking the right steps to make India safe for its women and children.

Den vollständigen Artikel können Sie hier lesen: http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/face-the-truth/3/

Der BBC-Dokumentarfilm kann hier angesehen werden.

New Delhi: Sage, 2013. 180 S., GBP 35,00

Im Kontext gesellschaftlicher und politischer Konflikte in Südasien werden Religion und Religiosität eher mit Blick auf ihre Gewalt fördernde Rolle als hinsichtlich ihres Potenzials für friedensbildende Prozesse betrachtet. Dies trifft vor allem auf essenzialisierende Repräsentationen des Islams und der Muslime als angeblich besonders gewaltaffin zu. Dieser Tendenz tritt Susewind mit seiner Studie entgegen und richtet den Fokus unter Bezugnahme auf Scott R. Applebys „Ambivalenz des Heiligen“ (1999) zum einen auf muslimische FriedensakteurInnen im westindischen Bundesstaat Gujarat und zum anderen auf die Bedeutung, die diese selbst im Zusammenhang ihrer friedensaktivistischen Tätigkeit ihrer Religion und ihrem Glauben beimessen.

Anstelle von Generalisierungen möchte er die Vielfalt und Individualität muslimischer FriedensakteurInnen aufzeigen, auch wenn dies in einer interessanten Spannung steht zu seinem Versuch einer typologisierenden Beschreibung von vier „ideal-typical ways of ‚being Muslim and working for peace‘“ in der Folgezeit nach den anti-muslimischen Gewaltausschreitungen 2002. Als solche beschreibt er als erstes „glaubensbasierte Akteure“, die ihre Kraft aus ihrer in-group, moralischen Überzeugungen sowie ihren orthodoxen rituellen Praktiken schöpfen. Mit dem Begriff der Ambiguität charakterisiert Susewind eine Tendenz unter diesen Akteuren, ihren Friedensaktivismus einerseits als ihrem Muslimsein inhärent und folglich für sie im Sinne einer politischen Handlung zwingend darzustellen, während sie gleichzeitig pragmatisch seien und für eine strikte Trennung von Religion und Politik argumentierten. Diese „Kultur der Ambiguität“ des indischen Islams präge selbst Anhänger reformistischer Bewegungen, die sich ideologisch gesehen auf einer „mission of disambiguation“ (S. 58) befänden. Hier ist die klare Abgrenzung glaubensbasierter Friedensakteure von „Fundamentalisten“ wichtig, die die Trennung der privaten und öffentlichen Bereiche aufheben wollen und eine politische Strategie der Dominanz verfolgen. In diesem Sinne definierte Fundamentalisten seien in Gujarat auch innerhalb glaubensbasierter Organisationen in der Minderzahl.

Als zweiten Idealtypus versteht der Autor die „säkularen Technokraten“, die weder von den religiösen Akteuren noch von der nichtmuslimischen Zivilgesellschaft beachtet würden. Tatsächlich meint er offenbar areligiöse Friedensakteure, die in Gujarat kaum mit glaubensbasierten Akteuren interagieren. Dies scheint jedoch nicht durch Differenzen über die Religion begründet zu sein, sondern durch unterschiedliche Schwerpunkte ihrer friedensaktivistischen oder entwicklungsorientierten Tätigkeit, die sich im Fall der „Technokraten“ nach der anfänglichen humanitären Arbeit oft in Richtung Rechtsberatung und Monitoring von Menschenrechtsverletzungen ausrichte. Wenn Susewind hier mit Blick auf die alltäglichen Handlungen dieser Gruppe von einem „long-term success of secularization“ (S. 75) spricht, bezieht er sich auf die Annahme einer Säkularisierung im Sinne eines linearen Prozesses, in dem Religion grundsätzlich an Bedeutung verliert, für das politische Handeln ebenso wie für das Leben von Individuen und Gruppen. Hier wäre folglich genauer zwischen „säkularisiert“ und „säkular“ zu unterscheiden, denn ob ein Mensch säkularen Prinzipien anhängt oder nicht, sagt an sich nichts über seine individuelle Religiosität aus, sondern über die Überzeugung, dass der Staat dieselbe Distanz gegenüber allen Religionen wahren und diese gleich behandeln sollte und/oder dass die Religion in erster Linie eine private und persönliche Angelegenheit sei und keine öffentliche Rolle spielen dürfe. Umgekehrt belegt die Debatte über den Postsäkularismus, dass es auch Atheisten gibt, die einer mit aller Konsequenz verfolgten ‚Privatisierung‘ von Religion kritisch gegenüber stehen – gerade, wenn diese primär von Minderheiten eingefordert wird. Laut Casanova zieht sich dieser „Riss“ oder fehlende Konsens bezüglich des Ortes und Stellenwertes von Religion in pluralen Gesellschaften folglich quer durch die unterschiedlichsten – religiösen oder areligiösen – Gruppen und Individuen hindurch.

Ausschließlich auf Friedensakteurinnen bezieht sich der dritte Idealtypus der sich „emanzipierenden Frauen“, bei dem bereits das Partizip im Unterschied zu den beiden ersten Gruppen auf eine höhere Dynamik in der wechselseitigen Prägung fluider religiöser Identitäten und friedensaktivistischer Tätigkeiten hinweist. Dieser Typus sieht sich laut Susewind hinsichtlich der erlangten Handlungsmacht zunehmend durch die patriarchalen Machtstrukturen innerhalb der in-group herausgefordert. Während sie sich anfangs noch auf den „islamischen Feminismus“ stützen würden, sagten sich einige Akteurinnen letztlich so weit wie möglich von der Religion los. Es wäre hier interessant, mehr über den Einfluss der sich „emanzipierenden Frauen“ aus Gujarat auf den neu entstanden Diskursraum des muslimischen Feminismus in Indien zu erfahren.

Als ebenso dynamisch betrachtet der Autor schließlich die „zweifelnden Professionellen“. Ohne sich zu stark mit der in-group zu identifizieren, fühle sich dieser vierte Typus von FriedensakteurInnen dennoch infolge der Gewalteskalation 2002 für sie verantwortlich und beginne frühere Annahmen bezüglich der Rolle von Religion sowie der eigenen Identität als Muslim/in zunehmend zu hinterfragen.

Der Band hätte stärker regionalhistorisch kontextualisiert werden können, insbesondere was den Islam und die Muslime in Gujarat angeht. Umgekehrt wäre es hinsichtlich der untersuchten FriedensakteurInnen interessant, eine Vergleichsmöglichkeit zu anderen Bundesstaaten zu haben, in denen es ebenfalls zu gewalttätigen Ausschreitungen zwischen ethnisierten Gruppen gekommen ist. Es stellt sich die Frage, wie spezifisch die vier Idealtypen für die zurückliegende Dekade in Gujarat sind, ob sie veränderlich sind und inwieweit sich in anderen Regionen Indiens ähnliche Dynamiken hinsichtlich der Wechselwirkung zwischen individuellen religiösen Identitäten und friedensaktivistischen Tätigkeiten feststellen lassen.

Der Band ist nicht nur für Südasieninteressierte relevant, sondern auch für Studierende regionalwissenschaftlicher Fächer empfehlenswert, die im Rahmen ihrer Abschlussarbeiten empirisch forschen möchten und sich dazu mit methodologischen Fragen auseinander setzen, auf die Susewind detailliert eingeht.

Veröffentlicht in: ASIEN The German Journal on Contemporary Asia, Nr. 133, Oktober 2014. S. 125-127.

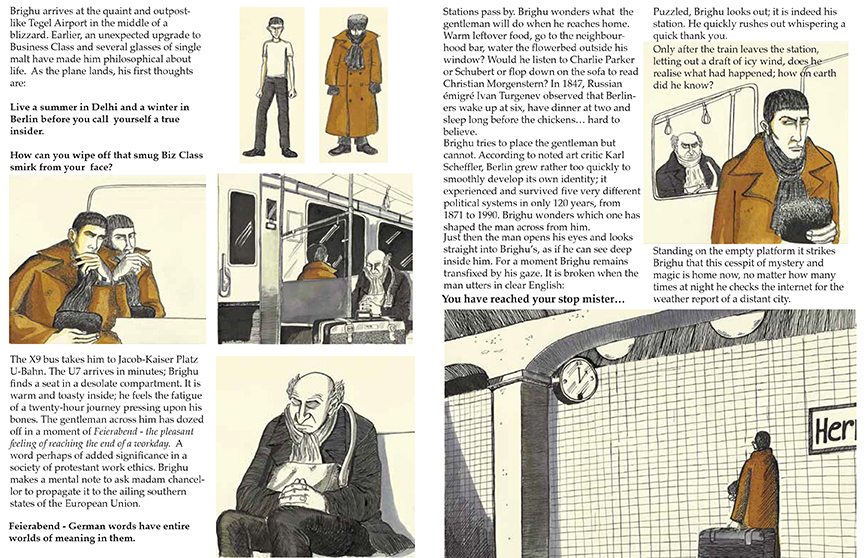

Sarnath Banerjee hat über seine Zeit in Berlin eine Graphic Novel verfasst, deren einzelne Episoden über die Webseite des Goethe-Instituts in Neu-Delhi angesehen werden können.

A Graphic Novel by Sarnath Banerjee: The Indian Brighu leads through Berlin in 17 episodes – from the arrival at Tegel Airport, first winter nights and the spring awakening to the topics anxiety, life and love.

Sarnath Banerjee created a Graphic Novel about his time in Berlin for the Indian daily newspaper The Hindu. The creativly complex and critical work combines experiences from Berlin with memories and historical events as well as cultural differences.

Episode 1: Arrival

Brighu arrives at the quaint and outpostlike Tegel Airport in the middle of a blizzard. Earlier, an unexpected upgrade to Business Class and several glasses of single malt have made him philosophical about life.

Link: Berlin mit Brighu – die einzelnen Episoden

Link: Mehr über die künstlerischen Arbeiten von Sarnath Banerjee

Max Arne Kramer

Victims, Villains or Agents?

The relative stability in the Valley of Kashmir after the early 2000s and the emergence of digital filmmaking around the same time furthered a wave of independent digital films that attempt to work through the history of the conflict. Ananya Kabir (2009) aptly calls the valley ’a territory of desire’ immersed in hyperbolic metaphors ranging from a tourist paradise to a terrorist hell.

In this essay I will introduce Sanjay Kak’s[1][2] Jashn-e-Azadi (2007), a film that not only deals with the history and memory of the conflict as an object of the film, but that articulates a historicity different from most other films on Kashmir be they from the Hindi-Film industry or the bulk of documentaries produced since the onset of independent digital filmmaking on the valley.

The scholar Mridu Rai recently said in her lecture ‘Language of Violence, Languages of Justice: The State and Insurgent Kashmir’[3], that Kashmiris can become visible either as victims or as perpetrators of violence. This is an observation that rings largely true for the corpus of documentary films I have been looking into. According to Brian Winston (2008) the victim has always been one of the ‚staple subjects’ of the griersonian realist documentary, and forms of the realist tradition are strong in India today[4]. It has been noted by Gyanendra Pandey (2000) that during times of what in India is called ‘communal violence’ a balanced account of the atrocities committed from ‚both sides’ is given, washing over the local context and dimensions of what has happened. In many documentary films on the Kashmir conflict (and other conflicts too) this parallel form is embedded in what Winston calls the ‘problem structure‘ of griersonian documentary. I will argue here, that Kak and the film’s editor Tarun Bhartiya challenge in the form of their film the wider distribution of atrocity images in South Asian visual culture by rearticulating them as a markedly Kashmiri historicity and temporality of the conflict questioning our notion of the Kashmir conflict ‘as a problem’ (between party A, B, C, etc. to be (un)solvable by experts, diplomats and state representatives).

These images of atrocities circulate on various platforms of visual activism – from the rather traditional traveling photo exhibitions and TV-newsreels to newer media-forms like You-Tube or multimedia-online archives of the conflict. Although I do not possess any precise data on their distribution and reception, these images surely connect to a certain frontal visual style I have observed in all of the above mentioned media and also in the more ‘dramatizing’ documentary films of my corpus. Many documentaries frame these images through a departmentalized view of Hindu and Muslim communities suffering together in equal measure under the signifier of an endangered secularism.

Style against Atrocities

Jashn-e-Azadi (2007) was the result of a long research beginning in 2003 with regular visits to the valley over the period of four years. Screenings of the film have become the scene of a number of violent public performances by the Hindu Right and intense debates – some calling the film ‘pro-Pakistani propaganda‘.

In a scene where the poet Zarif Ahmed Zarif is reciting one of his older poems (in fact pre 1989) atrocity images are breaking into the serenity of the recitation. It seems that the poet hides behind the flowers while darting his gazes and words back at the scenario of patrolling army men[5]. The bulk of the archival material used in this sequence comes from a person credited in Jashn-e-Azadi as the ‘unknown cameraman’. The material appeared, so the story goes, one day in front of Kak’s door after he contacted a number of journalists and friends who might know somebody who owns audio-visual material from the 1990s. It was cleaned and digitalized. There is a lot of material there, Kak told me, from both sides: most likely a small number of camera operators who shot for the army, for the militants, for both together and, sometimes, for themselves. Many hours of rather gruesome footage have been sighted by Kak and the films editor Tarun Bhartiya. Eventually only a few sequences made it into Jashn-e-Azadi. They pop up several times in the narrative as some kind of traumatic layer – marked by horizontal TV-lines. This marking has been done to give the spectator – as Bhartiya suggested – an idea of the absence of these minor images during the 1990ies. We may also get the feeling that we do not see the bodies in their iconic atrocity form. In fact, Bhartiya applied an editing strategy where he cut shortly before or after the climax of the actuality which – in the words of Bhartiya – “could also be frustrating for a viewer. Why are they not showing us the film? What we are showing in the present is equally [important] – it may not be that full of blood and war and all those kind of things – so, and if we show you the archive in its ‚full‘, would that make our argument more plausible?“

Now, how do these images and editing strategies add up to the film’s temporality? It is a long film, more than two hours full of ruptures evoking at once the difficulty of working through the traumatic memory of the conflict and the grip of a memory and a history of oppression that keeps it going.

In the words of Kak and Bhartiya, the film is “a narrative of feelings“ and “a compendium of Kashmiri resistance“: every fragment is meant to add up to the feeling of Azadi. The atrocity images, however, form an ambivalent traumatic layer. They are linked to the desire for Azadi but do not merge simply with this trajectory. As is clear from Bhartiya’s statement, there is a technique of defamiliarization at play to deal with both the affective and legitimizing power and the desensitizing danger of the atrocity image.

Sanjay Kak would repeatedly say before and after screenings that his films are “an argument“. While the film as an argument and the progressive understanding of history as ‘people’s struggle‘ suggest an immersion of the filmmaker’s subjectivity into the movement, I would argue instead that the form of the film rather evokes a self-reflexive[6] oscillation between inside and outside of the struggle analogous to the first person plural “we“ of the title: “This is how we celebrate freedom“.

Endnotes

[2] Sanjay Kak is a self-taught filmmaker who studied sociology and economics at the University of Delhi. He has recently become well known in the Indian Documentary community for three films that have entered the antagonistic spaces of social movements: Words on Water (2002) on the protest against the construction of the Narmada dams; Jashn-e-Azadi (2007) on the struggle for self-determination in Kashmir and Red Ant Dream (2013) on the struggle and culture of the tribal communist groups. Although born a Kashmiri Pandit, his political intervention into Kashmir ‘as a Kashmiri’ followed as a consequence of the aftermath of the 13 December 2001 attack on India’s parliament, where he became involved in the defense of one of the prime accused, the Delhi University teacher S.A.R. Geelani, both as a translator of a vital piece of evidence, and as a member of the defense committee set up to acquit Geelani.

[3] Ironically the police prevented the lecture to take place at its destined location in Srinagar: http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/jk-police-stop-lecture-by-author-mridu-rai-in-srinagar/ (access 07.01.15)

[4] James Beverdige was working from 1953-58 in Bombay for the Burmah Shell Oil Company. (http://www.beevision.com/JAB/cv.shtml, access 01.01.15). He was working with the griersonian educational notion of social uplift through documentary film. Later he helped to set up the Jamia Millia Islamia University’s Mass Communications Research Centre, which became a center for politically dedicated filmmaking in India (Vohra 2011, Schneider 2013).

[5] There is a version of the poem without the atrocity images on You Tube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_aglwJMifXE (access 07.01.14)

[6] As the filmmaker Surabhi Sharma once pointed out in a post-screening discussion of the film, the mulling voice-over of the commentator does not give us the impression of an immersion, but rather serves as a rational assessment of the feeling of azadi (self-determination).

References

Kabir, Ananya Jahanara. 2009. Territory of Desire: Representing the Valley of Kashmir.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pandey, Gyanendra. 2000. “In Defense of the Fragment: writing about Hindu-Muslim riots in India

today“. In Guha, Ranajit: A Subaltern Studies Reader 1986-1995, 1–34. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Schneider, Nadja-Christina. 2013. “Being Young and a ‚Muslim Woman‘uin Post-liberalization India: Reflexive Documentary Films as Media Spaces for New Conversations“. Asien 126 (January): 85–103.

Vohra, Paromita. 2011. “Dotting the I: The Politics of Self-Less-Ness in Indian Documentary Practice“. South Asian Popular Culture 9 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1080/14746689.2011.553887.

Winston, Brian. 2008. Claiming the Real: Documentary: Grierson and Beyond. Revised edition. London : New York: British Film Institute India.