Eine kommentierte Fotostrecke von Tamara Fina, die im Rahmen des Projektseminars Zukunftsentwürfe des Zusammenlebens: Konzepte, künstlerische Interventionen, mediale Utopien (BA Regionalstudien Asien / Afrika) unter der Leitung von Prof. Dr. phil. Nadja-Christina Schneider entstanden ist.

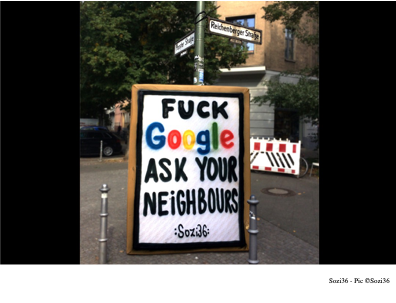

In Zeiten der Digitalisierung und Corona-Pandemie findet soziale Interaktion und Austausch mehrheitlich im virtuellen Raum statt. Dialoge verkommen zu Monologen, Diskussionen driften in Hetzereien ab, das Zusammenleben „vereinsamt“ hinter einem Bildschirm – was also kann in die Zukunft gedacht werden, um das Miteinander und Zusammenleben visionär zu gestalten?

Diese Fragestellung begleitet mich seit Beginn der Pandemie noch stärker als sonst und hat dazu geführt, dass ich mich im Rahmen dieses Projekts mit dieser Thematik befassen möchte. Digitalisierung ermöglicht einen schnellen, vereinfachten und globalen Austausch, was aber auch seine Kehrseite hat. Dies beleuchtet Netflix mit einer Dokumentation über Soziale Medien. Netflix wiederum wird von vielen Menschen als Unterhaltungsmedium genutzt, dabei kann in eine fiktive Welt eingetaucht werden, welche den Alltag vergessen lässt. Für jeden Geschmack hat Netflix etwas anzubieten, es wird sozusagen auf dem Silbertablett serviert. Ein paar wenige Mausklicks und die Realität verschwimmt mit der Fiktion, schnell und unproblematisch. Es wäre gelogen, würde ich mich von dieser virtuellen Welt ausschließen. Dabei ertappe ich mich, wie ich Freund*innen auf Serien und Dokumentationen anspreche und wir uns darüber unterhalten und diskutieren. Die scheinbare Welt von Netflix also, bestimmt gewissermaßen auch ein Stück meines Lebens. Ist dies besorgniserregend? Vereinsame auch ich hinter meinem Bildschirm? Wie oft treffe ich überhaupt noch meine Freund*innen? Ziehe ich Netflix Verabredungen mit Bekannten vor? Hemmt Netflix meine sozialen Interaktionen? Während mir diese Fragen durch den Kopf schwirren, überlege ich mir, welche Alternativen geschaffen werden können, um die gemeinsame Zukunft entscheidend zu gestalten.

„Die Doku ist gut und ich bin jetzt ein kritischer Zeitgeist. Aber daraus gelernt habe ich nichts, also gebt mir trotzdem Dopamin.“

Sozi36

(https://www.instagram.com/p/CMrQNboHF20/)

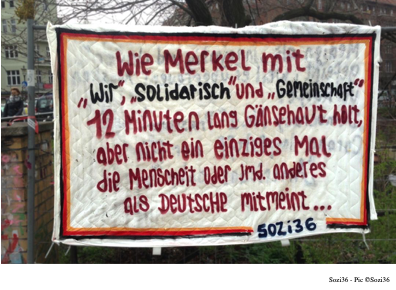

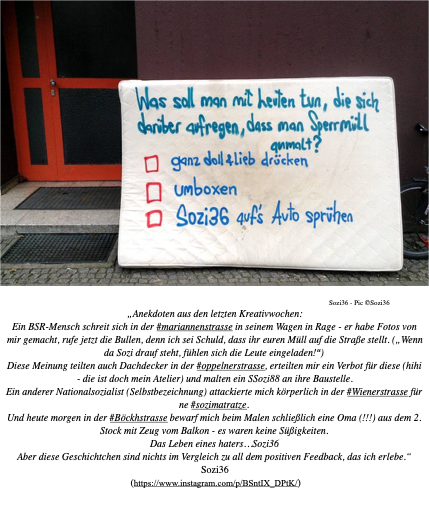

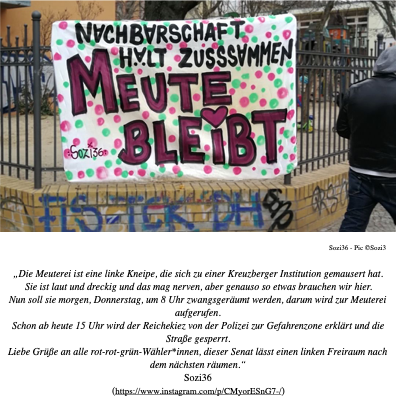

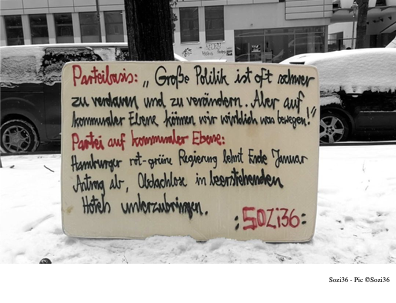

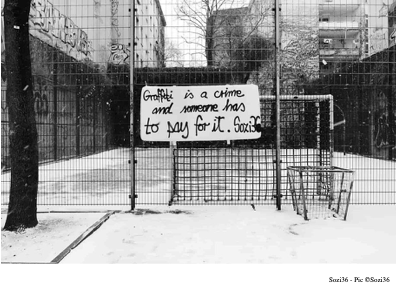

Im Fokus des Projektseminars steht der Grundgedanke respektive die Idee nach Asante, nach dem sich der Mensch frei denkend und kreierend, aber nicht hierarchisierend in die Zukunft entwickeln solle. Diese Idee soll als Ausgangslage benutzen werden. Nur wer sich selbst kenne so Asante, sei in der Lage eine Zukunftsvision hervorzubringen. Radikale Bewegungen müssten mit der Vergangenheit brechen können und mit einer provokanten Agency beginnen (1 vgl. Asante 52ff.). Diese Anschauung soll im urbanen Raum konzeptualisiert werden. Dafür eignet sich die Kunst des Graffiti-Künstler Sozi36, welcher in Berlin Kreuzberg immer wieder mit seinen Botschaften grössten Teils auf Matratzen verfasst, auffällt. Diese provozieren, regen zum nachdenken an, rufen Reaktionen hervor – für mich eine Form der aktivistischen Kunst, und ebenso ein Raum der die Möglichkeit erschafft zu diskutieren. Sozi36 verkörpert für mich mit seinen Äusserungen genau die Idee, dass der Mensch „out of the box“ denken sollte. Und dass er sich durch Botschaften vielleicht provoziert fühlt daraus aber eine Diskussion und auch ein sich weiterentwickeln stattfinden kann. Denn seine Aussagen sind unmissverständlich oder stellen eben Fragen gezielt missverständlich.

„Bei manchen Arbeiten versuche ich mit Metaebene (also durchaus missverständlich) zu arbeiten. Da verliere ich einige Leute, weil sie Meta nicht mitbekommen, aber das ist mir egal. Ich habe gehört, als Künstler müsse man auch etwas Denkleistung beim Betrachter lassen. Ich führe den Punkt nicht aus Klugscheißerei an, sondern weil ich mittlerweile sehr gerne und auch öfter mit Missverständnissen arbeite.“

Sozi36

Die Aussagen von Sozi36 prangern Ungerechtigkeiten an und sind sozial und gesellschaftskritisch geprägt. Für mich von enormer Aussagekraft. Sozi36 lässt aber auch in sein Inneres blicken und die Betrachter*innen ein Stück weit an sich heran. Im Projekt soll herausgearbeitet werden, inwiefern seine Kunst im öffentlichen Raum als dialogisches Medium und als Zukunftsvision verstanden werden kann.

Folgende Fragen sollen überprüft werden:

„Inwiefern kann die Graffiti Kunst von Sozi36 als dialogisches Medium im urbanen Raum Kreuzberg verstanden werden?“

„In welcher Hinsicht kann die Graffiti Kunst von Sozi36 im urbanen Raum Kreuzberg als Zukunftsvision betrachtet werden?“

Daraus resultiert folgende Hypothese:

„ Die Botschaften von Sozi36 sind visionär und bringen die Menschen im urbanen Raum zum Nachdenken, sie provozieren und rufen Reaktionen hervor, die einen Dialog ermöglichen.“

Graffiti hat ohne Zweifel einen interaktiven Charakter. Geschriebenes begegnete den Menschen bereits im antiken Alltag vor allem in Form von Inschriften. Schriftliche Informationen die nicht auf Papier verfasst waren, zierten Häuserfassaden, öffentliche Plätze, Ladenschilder u.ä. Die Beschaffenheit des/der Inschriftenträgers*in bestimmte die Beschaffenheit der Inschrift und damit auch deren Wahrnehmung. Eine Inschrift ist aber nicht nur ein einfacher Text (Inhalt) sondern hat auch ihren ganz eigenen Stil und Design welches das Produkt menschlichen Handelns ist. Die Intentionen der Hersteller*innen wird weiter transportieren und ruft somit auch Reaktionen hervor. Inschriften sind nicht einfach passive Dinge, sondern auch selbst Akteur*innen. Inschriften haben oft enge Bezüge zur gesprochenen Sprache, da sie das Merkmal besitzen, sich direkt an Passanten*innen und Leser*innen zu wenden. Auch Graffiti hat diese Eigenheit der Interaktion zwischen Text und Rezipient*in inne, wodurch ein Dialog entstehen kann. Die Botschaften und Inschriften laden Leser*innen einerseits zum Lesen und Verbleiben ein, können aber durch abschreckend formulierte Warnungen oder Provokationen, auch Wut oder Unbehagen auslösen. Beide Formen nutzen die Dialogform, denn sie treten direkt mit dem Lesenden in Kontakt. Graffiti steht in einem besonderen Verhältnis sowohl zu seinen Inschriftenträgern*innen als auch seiner Leserschaft, denn es wird ungefragt und auf primär nicht dafür vorgesehenen Flächen angebracht. Die Inschriften treten mit bereits Vorhan- denem in Interaktion, dies unter anderem im öffentlichen Raum. Oft ist nicht nur der/die Leser*in, sondern auch der/die unbeteiligte Passant*in mit einbezogen. Die Botschaften fordern ganz gezielt Aufmerksamkeit ein und ertappen die Leserschaft nicht selten „in flagranti“ beim Lesen der Botschaften. Provozieren diese, machen sich über die Betrachter*innen lustig, stellen ihr Weltbild in

Frage, hinterfragen ihre Werte und Normen. Graffiti kann wütend machen, stösst auf Unverständnis, löst Diskussionen aus. Graffiti Kunst stellt also eine Interaktion zwischen Verfasser*innen, Adressaten*innen her und ist dabei gleichzeitig Träger, Auslöser und Ergebnis von Interaktionen (2 vgl. Lohmann 2018: 103ff.). Graffiti dient sowohl als Medium, aber auch als Vermittlungsinstanz einer dialogischen Intention zwischen Machern*innen und Empfänger*innen. Ebenso werden Botschaften direkt oder indirekt, schriftlich zum Beispiel auf Social Media oder mündlich vor Ort kommentiert. Die Informationen und Aussagen werden weiter gegeben was weitere Interaktionen anregt. Die gesendeten Botschaften der Verfasser*innen entsprechen nicht immer den Nachrichten die empfangen werden. Graffiti im öffentlichem Raum ist nämlich nicht nur für einen bestimmten Personenkreis gedacht und demnach auch nicht nur für diesen rezipierbar. Die gesendeten Nachrichten können je nach Rezipient*in basierend auf dessen/deren Wissen, Wertvorstellungen, Idealen und Lesefähigkeit unterschiedlich interpretiert und weiter gegeben werden (3 vgl. Lohmann 2018:106f.). Es kann durchaus auch geschehen, dass der/die Empfänger*in dem Inhalt eine ganz andere Bedeutung beimisst als der/die Schreiber*in oder der/die Künstler*in intendiert hat (4 vgl. Burkart 1995: 38-41). „Deutschland dein Konzentrationslager brennt.“ Ein kurzer, aber prägnanter Satz, der Unverständnis, Unbehagen, aber auch Wut auslösen kann.

Gewisse Personen fühlen sich durch den Satz getriggert, andere vielleicht nicht. Die Aussage macht auf das brennende Flüchtlingslager in Moria aufmerksam. Eine Botschaft, die extrem viele Kommentare über Social Media erlangt hat. Es wurde diskutiert und argumentiert, und teilweise entstand der Eindruck, dass die von Sozi36 gesendete Botschaft nicht immer dem entsprach, was empfangen wurde. Die Nachricht kann in viele Richtungen gelesen, verstanden und interpretiert werden, und hat auf den ersten Blick einen abschreckenden Charakter. Dadurch kann aber eine Interaktion zustande kommen, aus der sich, aufgrund der Thematik, eine hitzige Diskussion entwickeln kann. Die Kommentarfunktion überlässt hier Adressaten*innen die Möglichkeit, schriftlich zu reagieren, aber auch dem Verfasser Sozi36 auf die Reaktionen einzugehen. Da die Botschaft im öffentlichen Raum platziert ist und ebenso auf Social Media zugänglich für alle, werden sozusagen auch unbeteiligte Personen mit einbezogen. Dies führt zu einem Diskurs, wobei die Botschaft den Auslöser einer Interaktion darstellt. Spannend dabei ist festzustellen, dass die Interpretationen konträrer und die Beiträge vielfältiger sind, wenn die Botschaft kontrovers ist. Dies führt unweigerlich zu einer Diskussion, in welcher verschiedene Positionen vertreten sind, und auch so zum Ausdruck gebracht werden können. Setzt man sich grundlegend mit Stadttext auseinander, so ist zu erkennen dass nicht nur unterschiedliche Formen der Aneignung von öffentlichem Raum sichtbar wird, sondern vielmehr wird auch verdeutlich, wie Machtbeziehungen im urbanen Raum zustande kommen. Der öffentliche Raum ist grösstenteils durch Reglementierung gekennzeichnet, welche vor allem von Ökonomie und Politik beeinflusst ist (5 vgl. Riegler 2020: 60). Monja Müller beschreibt den urbanen Raum als ein Ort in dem visuelle Kommunikation fast ausschliesslich politischen und kommerziellen Zwecken dient und der öffentlichen Raum nach Kriterien die dem Verkehr, den Massenkonsumkultur sowie der Repräsentanz politischer und ökonomischer Herrschaft untergeordnet sind gestaltet wird (6 vgl. Müller 2017: 445). Die Stadtpolitik hat sich die Aufgabe gemacht für Sicherheit und Ordnung zu sorgen, diese Funktion wird in Zeichen die im öffentlichen Raum platziert werden übersetzt (Verkehrs- und Hinweisschilder, Verbote und Gebote). Neben diesen Zeichen die in erster Linie für Sicherheit und Ordnung sorgen sollen, werden auch zahlreiche Werbebotschaften im urbanen Raum platziert, denn Werbung besitzt einen wichtigen Stellenwert und bringt die wirtschaftliche Validität einer Stadt zum Ausdruck. Der öffentliche Raum also fungiert als Aussenauftritt der Wirtschaftstreibenden (7 vgl. Werle 2013: 30f.). Unabhängige und individuelle Zeichenproduktion ist im

Stadtraum grundlegend nicht vorgesehen. Dennoch bringen sich Akteur*innen unautorisiert in den politischen und ökonomisch konstruierten Stadttext mit ein und nutzten damit das kommunikative Potential der urbanen Außenflächen. Die Intentionen und Motive dafür sind unterschiedlich: persönliche, politische, künstlerischer oder auch einfach kommerzielle. Dabei werden unterschiedliche, legale sowie illegale Aneignungsstrategien sichtbar. Bourdieu unterscheidet drei Raumkategorien: den physischen, den sozialen und den angeeigneten physischen Raum. Das Konzept des angeeigneten physischen Raum beschreibt die räumliche Verteilung von Gütern und Dienstleistungen sowie die Möglichkeiten von Akteur*innen mit ihren unterschiedlichen Möglichkeiten sich Räume anzueignen (8 vgl. Bourdieu 2010: 160). Der angeeignete physische Raum ist einerseits Ergebnis von sozialen Praktiken im Raum selbst aber auch Gegenstand von Kämpfen und Aushandlungsprozessen zwischen Akteuren*innen und unterschiedlichen Handlungsmöglichkeiten. Individuen nehmen öffentliche Räume, die auch der Repräsentation dienen, unterschiedlich war. Dies zum Beispiel aufgrund der eigenen Biographie. Entsprechend wird bestimmten Räumen eine mehr oder weniger grosse Bedeutung zuge-

schrieben (9 vgl. Etzold 2011: 193-196). Die staatlichen Institutionen sind für die Kontrolle und Überwachung des öffentlichen Raums zuständig. Die Reglementierung des öffentlichen Raums wirkt sich auch auf die Beschaffenheit des Stadttextes und die soziale Positionierung der Akteur*innen aus. Dies wiederum prägt räumliche Praktiken und somit auch die Ausdrucksform bei der Aneignung von öffentlichen Raum und kann als sozialer Kampf um städtisches Territorium verstanden werden. Unautorisierte Eingriffe in das Stadtbild untergraben die Autorität und Kontrolle der Stadtpolitik.

Sauberkeit und Sicherheit gelten primär als Argument um gegen die unerwünschten Verhaltens- und Nutzungsformen juristisch vorzugehen (10 vgl. Riegler 2020: 71). Der öffentliche Raum fungiert in erster Linie als Aushängeschild eines wirtschaftspolitischen Systems. Ordnung, Kontrolle und Sauberkeit sind vorgesehen und werden von staatlichen Institutionen umgesetzt. Dabei ist die Inneneinrichtung eines Wohnzimmers auf dem Bürgersteig nicht das vorgesehene Bild eines Stadttexts. Die Autorität der staatlichen Institutionen wird durch die Installation untergraben, denn Sofa und Sessel gehören grundsätzlich ins Wohnzimmer und nicht auf die Straße. Die Inneneinrichtung auf der Straße provoziert, denn es handelt sich dabei nicht um Sperrmüll, der zum Entsorgen in ein Hinterhaus geworfen, oder vor dem Haus hingestellt wurde, sondern vielmehr um bewusst in Szene gesetzte Kunst. Dabei hebt sich die Installation von sonst oft hingeworfenem Sperrmüll ab, indem sie einerseits Aneignung von sozialem Raum widerspiegelt, provoziert und Autoritäten untergräbt, anderseits durch das sehr ordentliche Anordnen der Möbel wiederum Ordnung und Sauberkeit verkörpern könnte. Mit dem Satz aber „Jetzt ist es Protestkunst“ diese vermeintliche Idealvorstellung sofort wieder zerschlägt. Die Installation, welche nicht aufgrund einer direkt ins Auge stechenden und provozierenden Botschaft auffällt, hat in ihrer Aussagekraft aber nicht weniger Stärke, denn sie stellt eine Form der Aneignung von sozialem Raum dar, wobei der Grundsatz von Ordnung und Sauberkeit aber nicht elementar verletzt wird, denn weder die Möbel noch die Anordnung der Möbel können als unordentlich oder schmutzig betrachtet werden. Setzt man sich abschliessend nochmals mit dem Ansatz von Asante auseinander, nach dem Zukunftsvisionen durch radikalen Bruch mit der Vergangenheit und provokanter Agency in die Zukunft entstehen können, so ist zu erkennen, dass Graffiti-Kunst mit dem Ansatz vereinbar ist: Gesendete Graffiti-Botschaften können konventionelle Werte und Normen in Frage stellen, sie hinterfragen, stossen auf Unverständnis, provozieren und lösen damit auch immer wieder Diskussionen aus. Graffiti stellt also eine Interaktion zwischen Schreibern*innen, Adressaten*innen und Dritten her. Dabei fungiert Graffiti als Träger, Auslöser und Ergebnis von Interaktionen und als dialogisches Medium zwischen Verfasser*in und Empfänger*in in Einem. Ebenso werden Botschaften direkt oder indirekt, mündlich oder schriftlich, zum Beispiel auf Social Media

(https://www.instagram.com/p/CMyorESnG7-/)

kommentiert. Informationen und Inhalte werden weiter getragen was weitere Interaktionen mit sich bringt. Durch Provokation kann Dialog entstehen. Der dadurch entstandene Prozess kann durchaus als provokante Agency verstanden werden, denn Dialog entsteht nicht innerhalb eines vorgegebenen Rahmens wie der Universität oder geleiteten Podiumsdiskussionen, sondern entwickelt sich durch einen ausserhalb dieses Rahmens befindenden Prozesses im urbanen Raum. Asante besagt weiter, dass der Mensch sich kreierend aber nicht hierarchisierend in die Zukunft entwickeln sollte. Ich möchte hier nochmals auf Monja Müller zurück greifen, denn sie beschreibt den urbanen Raum als ein Ort in welchem visuelle Kommunikation fast ausschliesslich politischen und kommerziellen Zwecken dient. Die Gestaltung des öffentlichen Raums wie oben erläutert erfolgt nach Kriterien, die dem Verkehr, der Massenkonsumkultur sowie der Repräsentanz politischer und ökonomischer Herrschaft untergeordnet sind. Diese politische und ökonomische Herrschaft basiert auf einem hierarchischen System. Dieses steht im Widerspruch zu Asante, der eben diese Hierarchisierung, welche auf dem Prinzip der ungleichen Verteilung von beispielsweise Gütern und Dienstleistungen basiert, kritisiert.

Betrachtet man nochmals das Konzept des angeeigneten physischen Raum nach Bourdieu, welches die räumliche Verteilung von Gütern und Dienstleistungen sowie die räumliche Verteilung von Akteur*innen, die unterschiedliche Möglichkeiten haben sich Räume anzueignen ausführt, kann eine Verbindung zu Asante gezogen werden. Der angeeignete physische Raum ist einerseits Ergebnis von sozialen Praktiken im Raum, aber auch Gegenstand von Kämpfen und Aushandlungsprozessen zwischen Akteuren*innen und unterschiedlichen Handlungsmöglichkeiten. Unautorisierte Eingriffe in den Stadttext untergraben die Autorität und Kontrolle der Stadtpolitik. Sauberkeit und Sicherheit gelten primär als Argument, um gegen die unerwünschten Verhaltens- und Nutzungsformen juristisch und exekutiv vorzugehen. Unabhängige und individuelle Zeichenproduktion ist im Stadtraum unerwünscht. Dennoch nehmen Akteur*innen umautorisiert diesen Raum als kommunikatives Potential in Anspruch im gleichzeitigen sozialen Kampf um städtisches Territorium. Dies ist Ausdruck einer Bewegung, die sich gegen den ökonomisch und politisch konstruierten Stadttext welcher auf Hierarchisierung beruht, stellt und somit auch der Zukunftsvision von Asante entsprechend gerecht wird. In meinem Projekt habe ich mich bewusst mit den Botschaften des Graffiti- Künstlers Sozi36 auseinander gesetzt, denn für mich verkörpert er die Attribute provokant, Aneignung von Raum oder aber auch das Infragestellen von Autorität und Kontrolle durch staatliche Institutionen. Sozi36 polarisiert mit seinen Botschaften. Schon das Verfassen von Botschaften auf Matratzen führt zu Diskussionen unabhängig davon ob es angemessen ist Sperrmüll zu bemalen oder nicht. Hier prallt der kommerzielle Gedanke von Stadtbild auf einen innovativen. Seine Aussagen wiederum spielen mit Missverständnissen und provozieren, lassen Nachdenken, stellen die Gesellschaft mit ihren Normen und Werten in Frage. Seine Kunst kann zweifelsohne als dialogisches Medium verstanden werden. Adressat*innen fühlen sich provoziert, diskutieren über Social Media über die Inhalte der Botschaften, posieren vor Aussagen auf Matratzen, während andere wiederum die Polizei rufen um den „Unruhestifter“ möglichst aus dem Stadtbild entfernen zu lassen. Zu guter Letzt gibt es auch noch diejenigen die selbst Hand anlegen um wieder Kontrolle und Sicherheit zu erlangen und seine Arbeiten entsorgen.

Seine Botschaften polarisieren, bringen Interaktionen verschiedenster Formen hervor und fungieren somit als dialogisches Medium. „No More Moria Europäische Werte siechen in den Lagern und liegen auf Grund des Mittelmeers.“ Die Botschaft ist unmissverständlich. Europäische Werte werden klar und deutlich in Frage gestellt. Der Satz regt zum Nachdenken an, denn er erinnert unumgänglich an die geflüchteten Menschen, welche in Moria festsitzen, oder auf dem Weg dahin auf tragische Weise ihr Leben verloren haben. Menschen, die auf der Flucht Richtung Europa sind. Im Kontrast dazu das Posieren vor einer Matratze, in Berlin, Europa. Ein Bild, welches fast schon etwas Geselliges und Fröhliches ausstrahlt. Zwei Formen Botschaften an Adressat*innen zu bringen, beide auf ihre eigene Art und Weise. Beide aber rufen Reaktionen hervor, wodurch ein Dialog entstehen kann. Und obwohl die beiden Aussagen auf den ersten Blick konträr erscheinen, kann eine Verbindung hergestellt werden. Denn auf gewisse Weise werden in beiden Botschaften die europäischen Werte und Normen in Frage gestellt.

Die eine Botschaft ist beim Lesen eindeutig, denn der Begriff Moria assoziiert Lager, geflüchtete Menschen, Brand, Kritik an der Europäischen Union. „Ist mir zu deutsch in Kaltland. Ich gönn mir Namibia“ kann mit Urlaub assoziiert werden, aber auch mit der Deutschen Kolonialgeschichte in Namibia. Es ist also zu erkennen, dass die gesendete Nachricht je nach Rezipient*in, basierend auf dessen/deren Wissen, Wertvorstellungen, Idealen und Lesefähigkeit, unterschiedlich interpretiert und weiter gegeben werden kann. Und dass die eine Person die Nachricht mit Urlaub in Verbindung bringt, eine andere aber mit Kritik an der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte und somit auch europäische, respektive Deutsche Werte und Normen in Frage stellt. Die verschiedenen Interpretationen lassen Raum für Aus- tausch und Diskussion.

Die Frage also

„Inwiefern kann die Graffiti Kunst von Sozi36 als dialogisches Medium im urbanen Raum Kreuzberg verstanden werden?“

kann damit beantwortet werden, dass Dialog über die Botschaften, die er versendet entstehen kann, weil die Inhalte seiner Aussagen nicht dem gängigem Stadtbild und -text entsprechen und sie auf nicht dafür vorgesehenen Objekten (Sperrmüll) platziert werden. Ein Dialog muss nicht immer positiv konnotiert sein. Darum ist auch diese radikale Bewegung, die Asante beschreibt, in dem von mir gewählten Beispiel so zwingend nötig und wichtig zu erwähnen. Denn ich verbinde radikal und provokant als Zukunftsvision eben genau mit den Botschaften von Sozi36, die oft sehr provokant sind und entsprechend auch starke Reaktionen hervorrufen können. Und dieser Ansatz führt dazu, dass die Menschen wieder miteinander in Dialog treten können auch wenn dieser kritisch und manchmal auch eher konfrontativ oder bisweilen sogar aggressiv sein sollte. Es findet Austausch und zwischenmenschliche Reibung statt, welche wichtig für eine visionäre Zukunftsgestaltung ist.

Folglich lässt sich folgende Fragestellung beantworten

„In welcher Hinsicht kann die Graffiti Kunst von Sozi36 im urbanen Raum Kreuzberg als Zukunfts- vision betrachtet werden?“

Seine Kunst ist visionär, weil sie sich aus der Normalität, also den hierarchischen Strukturen die für Ordnung, Sauberkeit Kontrolle und Autorität sorgen sollen, heraus bewegt. Diesen Kampf um städtisches Territorium trägt er insofern aus, indem er Sperrmüll, welcher das Gegenteil von Ordnung und Sauberkeit bedeutet, gekonnt in Szene setzt und sich dabei auch nicht vor negativen Reaktionen scheut. Mit seinen Aussagen und den dafür ausgesuchten Mitteln (Matratze, Wahlplakate, Sofa usw.) bringt Sozi36 die Kontrolle und Autorität der Stadtpolitik ins wanken und stellt somit ein Gegenpol zum politisch und ökonomisch konstruierten Stadttext dar. Seine Kunst hat auch einen vi- sionären Charakter, weil es ihm gelingt Dialog und Aushandlungsprozess von urbanen Räumen und deren Verteilung von Gütern und Dienstleistung durch seine ganz eigene individuelle Aneignungsform und auf seine Art und Weise zu erschaffen. Trotzdem wird seine Kunst von gewissen Institutionen kriminalisiert, vielleicht gerade deshalb, weil er Autoritäten untergräbt und sich aus der Normalität heraus bewegt. Denn seine Botschaften sind kritisch, mutig, unkonventionell. Dialoge können entstehen, und ebenso wird Raum für Aushandlungsprozesse durch seine Kunst erschaffen. „Graffiti is a crime and someone has to pay for it.“ Ich stelle mir abschliessend die Frage, wer am Ende dafür zu bezahlen hat? Vielleicht wir alle, wenn wir uns nicht aus unserer angenehmen „Bubble“ heraus bewegen und uns mutig aufeinander zu, anstatt immer mehr nur dem Bildschirm zuwenden.

Über die Autorin: Tamara Fina ist Studentin der Asien/Afrikastudien (MA) der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. Ihre Arbeitsschwerpunkte sind Literatur, Kultur, Identität und postkoloniale Strukturen in zentralafrikanischen Regionen.

Literatur:

Asante, Molefi Kete (2021). Afrocentricity and Afrofuturism 2.0: Countdown to the Future In: Natasha A. Kelly (2021). (ed.) The Comet – Afrofuturism 2.0. bpd, Bonn. S. 47-77.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2010). Ortseffekte. In: Ders. et al. (Hg.): Das Elend der Welt. Gekürzte Studienausgabe, 2. Auflage. UTB GmbH, Konstanz. S. 159-167.

Burkart, Roland (1995). Kommunikationswissenschaft. Grundlagen und Problemfelder; Umrisse einer interdisziplinären Sozialwissenschaft. 2. Aufl. Böhlau Verlag, Wien.

Etzold, Benjamin (2011). Die umkämpfte Stadt – Die alltägliche Aneignung öffentlicher Räume durch Straßenhändler in Dhaka (Bangladesch) In: Holm A. & D. Gebhard (Ed.): Initiativen für ein Recht auf Stadt: Theorie und Praxis in städtischer Aneignungen. VSA Verlag, Hamburg. S. 187-220.

Kappes, Mirjam (2014). Graffiti als Eroberungsstrategie im urbanen Raum. In: Warnke, Ingo H./ Busse, Beatrix (Hrsg.): Place-Making in urbanen Diskursen – Interdisziplinäre Beiträge zur Stadtforschung. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Boston / Berlin. S. 443-476.

Lohmann, Polly (2018). Graffiti als Interaktionsform. Geritzte Inschriften in den Wohnhäuser Pompejis. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Boston / Berlin.

Müller, Monja (2017). Reclaim the Streets! Die Street-Art-Bewegung und die Rückforderung des öffentlichen Raumes. Am Beispiel von Banksys. Better out Than In. Und Shepard Faireys Obey Giant-Kampagne. Books on Demand, Norderstedt.

Riegler, Anna (2020). Die urbane Zeichenlandschaft. Aushandlungsprozesse um Stadttext. In: Jg. 1 (2020), H. 1: Sonderband 1. msc_lab b: Die Strasse S.59-72 Elektronische Ressource.

Werle, Bertram (2013). Werbung und Baukultur: Stadt im Spannungsfeld. In: Internationales Städteforum Graz (Hg.): Die umworbene Stadt. Stadtgestalt und Werbung im Fokus von Denkmalpflege und Baukultur, ISG Tagungsband 2013, Graz. S. 27-33.

Onlinequellen: http://www.melodieundrhythmus.com/mr-1-2018/attacken-auf-die-linksliberale-komfortzone/

[Zugriff: 22.05.21]

https://www.urbanpresents.net/2020/04/der-eigenweg-von-sozi36/ [Zugriff: 22.05.21]

https://www.instagram.com/sozi.36/ [Zugriff 12.06.21]

Navkiran Natt, who was originally trained as a dentist and has a degree in film studies, is an activist who is involved in the current farmers‘ movement against three new, highly controversial agricultural laws in India. She actively participates in protests on the ground and co-edits Trolley Times, a creative multilingual newsletter by and for the movement.

In this conversation, Dr. Fritzi-Marie Titzmann, postdoctoral fellow of the RePLITO project at Humboldt University in Berlin, talks with Navkiran Natt about the current scenario of the farmers‘ protest, the motivation for her own activism, and especially the media practices she uses to circulate information about and solidarity with the movement.

Navkiran Natt describes the social dynamics of the physical protest sites as marked by mutual solidarity and community spirit that can serve as a model of peaceful human coexistence. In this, they also bear resemblance to neglected and marginalized repertoires of living together. In the context of social movements such as the ongoing Indian farmers’ protest, mediatized expressions of solidarity have the ability to enhance and transnationally circulate this experience of togetherness characterized by acceptance and support.

“Claims to loitering are fundamentally imagined as collective rather than individual. This sense of the collective is often missed by arguments that understand such protests as individualistic and neo-liberal (Shilpa Phadke, “Defending Frivolous Fun: Feminist Acts of Claiming Public Spaces in South Asia”, 2020:289).

Shilpa Phadke is a Professor at the School of Media and Cultural Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She is co-author of the critically acclaimed book Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets (2011) (together with Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade) and co-director of the documentary film Under the Open Sky (2016).

Today, shrinking city-space, an increasing privatization and surveillance of public space as well as the ongoing socio-spatial segregation make it even more difficult to imagine an inclusive space where different marginalized groups and communities can come together to disrupt the taken-for-granted segregation of people, hierarchies, boundaries and build new alliances.

Ten years after the publication of “Why loiter?” and subsequent emergence of a loitering movement in South Asian cities, Shilpa Phadke reflects in her conversation with Nadja-Christina Schneider on the continued relevance of key claims of the path-breaking book.

Cinema of Resistance (COR) is a grass roots film screening collective from India that focuses on forming new cultural spaces in small towns and villages through the screening of alternate films. The collective’s journey that began in 2006 with the Gorakhpur Film Festival has been instrumental in creating new circulatory networks around such films that deal with issues including labor rights, gender justice, human rights and environmental issues. Within this network, the screening of films become a catalyst for creating discussion spaces around such issues. Cinema of Resistance festivals are a regular event in the cultural calendar of many cities and towns outside the major metropolises of India including Udaipur, Patna, Gorakhpur, Allahabad, Lucknow, Ramnagar and Nainital.

In this interview with Dr. Shweta Kishore, the national convenor of Cinema of Resistance, Mr.Sanjay Joshi talks about the importance of alternate cinema in building interactive spaces where ordinary people can find ways of expression that goes beyond limits of state censorship and neoliberal logic of engagement. Dr. Shweta Kishore is a lecturer of Screen and Media at RMIT, Australia. Sanjay Joshi has made several documentaries and he has so far curated over 71 film festivals and screenings for cinema of resistance.

Shabnam Virmani is a documentary filmmaker from India and the initiator of the Kabir Project. Through the Kabir Project she has been exploring the philosophy of Kabir, Shah Latif and other mystic poets through a deep engagement with their oral folk traditions for close to two decades, ever since the riots of Gujarat in 2002 propelled her on this quest. Her inspiration in this poetry has taken the shape of 4 documentary films on Kabir, a digital archive called Ajab Shahar, writing books, organising urban festivals and rural yatras, singing and performing herself and infecting students with the challenge of mystic poetry. Currently she is working on a new idea to bring the power of mystic poetry and folk singers into school classrooms.

In this conversation, Dr. Fathima Nizaruddin, a postdoctoral researcher with the International Research Group on Authoritarianism and Counter Strategies (IRGAC) of the Rosa Luxemburg-Stiftung interviews Shabnam Virmani about her journey with the Kabir Project for almost two decades. Shabnam talks about the relevance of the world view of Kabir and other mystics in contemporary times and the way in which Kabir Project has been able to carve out spaces of co-existence through the use of various means including songs, films, books, journeys as well as online platforms and a digital archive. She expands on the possibilities of creating circulations that can provide new repertoires of living together by drawing from poetic traditions around the work of mystics like Kabir who question the very basis of distinctions between the self and the other.

Im vergangenen Winter eröffnete Emilia von Senger unweit des Hermannplatzes ihre erste eigene Buchhandlung – mitten in der Pandemie, während Einzelhändler*innen bundesweit um ihre Existenzen bangten. In von Sengers Buchhandlung She Said brachen jedoch noch bevor die Bauarbeiten überhaupt abgeschlossen waren schon scharenweise Kund*innen herein. Besonders während der Wochenenden im Lockdown standen die Berliner*innen teilweise über eine Stunde in der Schlange, um in den schicken Laden zu gelangen. Vermutlich trugen die im Lockdown sehr begrenzten Freizeitmöglichkeiten auch ihren Teil zum Andrang bei, Hauptgrund wird aber nichtsdestotrotz das feministische Konzept der Buchhandlung sein – bei She Said finden Kund*innen zeitgenössische und diverse Literatur. Der Clou, es werden nur Bücher von weiblichen und queeren Autor*innen verkauft. Neben deutsch- und englischsprachiger Prosa findet man auch unterschiedliche Sachbücher zu Themen wie kritische Männlichkeit, Arbeit, Soziales und Anti-Rassismus. Eine kleine Lyrikabteilung gibt es ebenfalls, genauso wie eine besonders schöne Ecke mit diversen Kinderbüchern, die Gendernormen aufbrechen und eine Vielfalt von Identitäten abbilden. Weitere Kategorien sind auch „Non-Western“-Bücher und postmigrantische Literatur. She Said hat zusätzlich zwei Onlineshops – einen für Bücherpakete mit den Lieblingsbüchern des Teams, Postkartenkollektionen und T-Shirts. Der zweite Onlineshop dient für weitere Buchbestellungen, die man bis 18 Uhr einreichen kann und am nächsten Tag bereits vor Ort abholen kann.

Wer in der Buchhandlung mit dem Lesen nicht warten möchte, kann sich im integrierten Café von She Said setzen und bei einem Kaffee direkt die neuerworbene Literatur aufschlagen. She Said ist nämlich eine Buchhandlung zum Verweilen, hier trifft sich ein aufgeklärtes Publikum, das bewusst Literatur konsumiert. Die Literatur und das Café sind dabei nur ein Teil von She Said. Ein vielfältiges Veranstaltungsprogramm lässt die Buchhandlung zu einem Community-Ort werden, an welchem Lesungen von Autor*innen wie Emilia Roig („Why We Matter – Das Ende der Unterdrückung“) und Şeyda Kurt („Radikale Zärtlichkeit“), aber auch Talks und Livestreams stattfinden. Der Standort der Buchhandlung – der Kottbusser Damm, der die Berliner Szenebezirke Kreuzberg und Neukölln vereint, bringt zusätzlich das moderne Großstadtpublikum, welches man sicherlich zur Zielgruppe von She Said zählen kann. Wie zeitgemäß She Said ist, lässt sich an der Onlinepräsenz der Buchhandlung gut erkennen. Schon während der Bauarbeiten konnte man über Instagram mitverfolgen, wie She Said Stück für Stück entsteht und wer an den jeweiligen Prozessen beteiligt ist. Über ihre Social Media Kanäle promoten sie nicht nur die Veranstaltungen, Literatur und die hausgemachten Spezialitäten des Cafés, sie vernetzen sich so auch mit der Community, holen sich Feedback und stehen im direkten Austausch mit den Besucher*innen und Kund*innen. Von Senger selbst gab an, vor der Entstehtung von She Said bereits auf Instagram in der sogenannten Bookstagram-Community vernetzt gewesen zu sein, selbst die erste Idee von der Buchhandlung habe sie auf ihrem Account geteilt.

Copyright: @shesaidbooks

Inspiration für das queerfeministische Konzept von She Said ist die cishet männlich dominierte Literaturindustrie samt Kanon gewesen, dem von Senger sich widersetzen wollte. Noch immer sind FLINTA* und queere Männer in der Literaturwelt unterpräsentiert; sie werden im Vergleich zu ihren cishet männlichen Kollegen seltener bei Literaturagenturen unter Vertrag genommen, veröffentlicht und mit Preisen und Förderungen ausgezeichnet. Handfeste Zahlen zu der Benachteiligung von Frauen lieferte dazu unter anderem die Pilotstudie „Sichtbarkeit von Frauen in Medien und im Literaturbetrieb“ unter dem Stichwort #Frauenzählen von der verbandsübergreifenden AG DIVERSITÄT, welche 2018 ins Leben gerufen wurde. Im März 2018 wurden im Rahmen dieser Studie 2036 Rezensionen aus 69 deutschen Medien (Print, Hörfunk und TV) analysiert.

Die Ergebnisse sind sicher nicht sonderlich überraschend, aber dennoch ernüchternd – es wurden erheblich mehr Bücher männlicher Autoren besprochen und auch die Kritiker*innen waren überwiegend männlich. In konkreten Zahlen heißt das: Zwei Drittel der thematisierten Bücher stammten von Autoren. Obwohl diese Studie auch große Schwachstellen hat – so ist Gender hier komplett binär dargestellt, beispielsweise nichtbinäre Autor*innen werden schlichtweg gar nicht einbezogen, ein intersektionalerer Ansatz wäre natürlich wünschenswerter gewesen.

Dennoch schafft es die Studie auf den Sexismus in deutschen Literaturbetrieben aufmerksam zu machen und Impulse zu setzen, gegen diesen zu vorzugehen. Läden wie She Said tragen ebenfalls einen erheblichen Teil dazu bei, Autor*innen zu stärken, die queer oder nicht männlich sind.

Trotz alledem wurden auch kritische Stimmen gegen She Said erhoben. Die meiste Kritik, die gegen von Senger ausgesprochen wurde, bezieht sich allerdings auf ihren zuerst intransparenten Umgang mit ihrer Familiengeschichte. Ihr Urgroßvater war während der NS-Zeit als Wehrmachtsgeneral und als Kommandant einer Panzerdivision tätig. Die Vermutung lag schnell nah, dass die Gelder für die Finanzierung der Buchhandlung von den geerbten Nazi-Geldern der Familie stammen könnten.

Die Diskussion um von Sengers Familienhintergrund starteten die Künstlerin Moshtari Hilal und der Autor und politische Geograf Sinthujan Varatharajah auf Instagram. In einem Video thematisierten sie die Problematik um Nazi-Gelder im Kunstbetrieb im Allgemeinen und nahmen She Said hier als Beispiel. Von Senger reagierte schnell auf den medialen Druck und räumte den Fehler ein, diesen Teil ihrer Familiengeschichte nicht transparenter offengelegt zu haben. Auf ihrem Instagram-Account veröffentlichte sie das Statement, „Einen queerfeministischen Buchladen zu eröffnen und gleichzeitig nicht über seine Nazi-Familiengeschichte zu sprechen, geht nicht“.

Sie beteuerte jedoch, die Gelder für She Said stammten aus einer anderen Quelle. Darüberhinaus sollte man nicht außer Acht lassen, dass die queerfeministischen Bücher, welche von Senger in She Said verkauft, zur NS-Zeit verboten und verbrannt worden wären; nichtsdestotrotz ist es wichtig diese Debatten zu führen und auch bei feministischen Projekte wie She Said genau hinzuschauen und nicht nur die Konzepte, sondern auch die Mittel, mit welchen sie umgesetzt werden, zu reflektieren.

Über die Autorin: Elena Schaetz ist Studentin der Afrikawissenschaften (MA) an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Ihre Arbeitsschwerpunkte sind Literatur, Kultur, Gender und Queerness in südafrikanischen Regionen.

Akwaeke Emezi was born in 1987 in in Umuahia, Nigeria and studied at New York University. In 2017, they won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize for Africa. Emezi’s debut novel Freshwater was published one year later. Their latest novel The Death of Vivek Oji was published in 2020 in the U.S.

The New York-based author of Igbo Tamil descent, who also describes themselves as a „nonbinary trans and plural person“ explained in several interviews (e.g. Deutschlandfunk Kultur) that many elements of the novel are of autobiographical origin. Freshwater tells the story of a „plural individual“ – a transgender person called Ada whose body is inhabited by several personalities and occupied by various spirit beings from Igbo mythology.

The novel combines themes of gender, sexual violence, mental health, trauma, physicality and identity with elements of Igbo culture, specifically the Ogbanje. Ogbanje are evil spirits, the literal translation from the Igbo language is „children who come and go“. The Ogbanje picks a family and enters the body of one child to kill him or her before puberty. After the Ogbanje is done with that child, it returns to the same family to be reborn and the cycle repeats itself. Dr. Sunday Ilechukwu states in her article „Ogbanje/abiku and cultural conceptualizations of psychopathology in Nigeria“ that Ogbanjes choose predominantly female children. Furthermore she explains the suffering of Ogbanje children: „The most common psychiatric symptoms are visual hallucinations […], aggressive/destructive behavior […], conversion/dissociation disorders […], and vivid dreams about water […]The loss of control, unexplained symptoms (conversion), changes in conscious expression (dissociation), and dreams about water […] and play (with spiritual companions) suggest Ogbanje to the patients“. The aspect of water is, of course, particularly interesting in relation to the title of the novel.

In the Nigerian context, the phenomenon of Ogbanje is well known, Ogbanje is also used in speech as a synonym for stubborn children. Ogbanje are also a recurring literature motif from Nigeria and from the Nigerian Diaspora. One of the most known examples for this is the character Ezinma in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

Ada is one of those Ogbanje children. She is the daughter of a Nigerian doctor named Saul and his Malaysian wife, Saachi. From a young age, it is clear that Ada is different from the others which shows for example in self-injurious behavior. While most Ogbanjes die as children, Ada survives. But things get worse the older she gets. When Ada moves to the U.S. at 16 to go to college in Virginia, the Ogbanje’s voice grows stronger. Ada gets raped on her campus and the Ogbanje splits into many entities as a result. One entity named Asughara is especially powerful and dangerous. Asughara is a female spirit that wants to avenge Ada, but destroys her in doing so. There are times when Ada gives complete control over to that raging spirit. Asughara is a violent force, ruthlessly seeking sexual encounters, destroying Ada’s relationships in the process. She uses Ada’s body to seduce and to break men, but also to harm Ada. She cuts and hurts herself in many other ways, from unprotected casual sex, to excessive drinking and disordered eating. Ada tries to oppose Asughara, which almost ends in suicide, but she manages to get rid of her.

Ada goes through many relationships, some of them are intense or even traumatic, some are just fleeting and weak in meaning. However, Ada’s most intense relationships are not with other people, but with the voices inside her that contradict each other, take her over and tear her apart. Ada also carries a male entity within herself, this one is named Saint Vincent, which in contrast to Asughara is full of gentleness and makes her date women and explore her queer identity. She experiences gender dysphoria and tries to find ways to deal with it first by binding her chest and eventually by having surgery to reduce the size of her breasts.

Freshwater deals a lot with embodiments. Ada struggles with being in her body and with the trauma that is linked to this body, as well as with the entities living within her. Freshwater is about being trapped in a body, but the multiple personalities also enable a complexity and open up new perspectives.

By presenting the Ogbanje as reality in their novel, Emezi pays tribute to the elements of Igbo culture and develops the literary motives even further. With the colonization of Nigeria, much of the Igbo culture was lost, suppressed and discarded. With Freshwater, the author shows us a small insight into the multifaceted Igbo culture, but mixes this with modern twists. The novel blurs the lines between Igbo gods, mental illnesses and gender issues.

These themes are certainly not easy, but the narrative style that conveys them is outstandingly poetic and stylistically so powerful that it keeps the reader hooked. Freshwater is characterized by a thrilling narrative style, switching from the collective Ogbanje who refer to themselves as “We” to Ada herself, who barely narrates her own story, to the spirit Asughara. The alternating switching between characters and voices can first be irritating for the reader but it’s also one of the main points why the novel is so captivating.

After prize-longlisted Freshwater was praised by both critics and by the public on an international scale, Emezi is following up with a second novel called The Death of Vivek Oji. This new novel shares Freshwater’s themes, particularly in its exploration of ideas of selfhood, identity and embodiment, along with spirituality.

About the author:

Elena Schaetz is a student of African Studies (MA) at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Her research focuses on literature, culture, gender and queerness in South African regions.

von Elena Schaetz

copyright: Natalie Seery/HBO

Seit dem Erfolg ihrer Sitcom Chewing Gum (2015-2017) und spätestens nach ihren Rollen in den Netflix-Produktionen Black Earth Rising (2018) und Black Mirror (2017) wird die britisch-ghanaische Schauspielerin und Drehbuchautorin Michaela Coel als vielsprechende Künstlerin gefeiert. Ihre neuste Dramaserie, I May Destroy You, wurde im Juni 2020 erstmalig auf HBO und BBC One ausgestrahlt und wird bereits jetzt als eine der wichtigsten Produktion des Jahres betitelt. Grund dafür sind nicht nur die Themen, die die Serie verhandelt, sondern auch wie und aus welchen Perspektiven dies geschieht.

I May Destroy You ist die Geschichte von Arabella, einer jungen Londoner Autorin, welche in einer Partynacht K.O.-Tropfen untergemischt bekommt und anschließend bewusstlos Opfer einer Vergewaltigung wird. Am nächsten Morgen wacht sie mit einer Platzwunde und einer großen Erinnerungslücke auf und begibt sich zunehmend verzweifelt auf die Suche nach Hinweisen. Dabei geht es jedoch nicht nur um das Identifizieren des Täters, sondern auch um das Finden von Bewältigungs- und Verarbeitungsstragegien.

Entscheidener als der grobe Plot sind jedoch die kleinen Facetten der Serie, die verschiedene Perspektiven bieten: Da ist zum Beispiel Arabellas bester Freund Kwame (Paapa Essiedu), der ein Grindr-Date nach dem nächsten hat, bis auch er Opfer einer Vergewaltigung wird. Durch die Figur Kwames schafft es Coel, mehrere Tabu-Themen gleichzeitig aufzumachen – sensible black masculinity, black gayness und auch die in Medien selten gezeigte Seite von männlichen Opfern sexueller Gewalt.

copyright: HBO

Gerade Schwarze Männer werden in den meisten Film- und Fernsehproduktionen oftmals sehr hypermaskulin oder gar aggressiv gezeigt; sie sind Sportler, Dealer, Gangster oder Aufreißer. Das rassistische Klischee des hypersexuellen Schwarzen Mannes wird vielfach reproduziert. Coel hingehen zeigt eine andere Schwarze Männlichkeit, die auf Menschlichkeit beruht. Wir sehen Kwame als guten Freund Arabellas, der sich nach der traumatischen Erfahrung der Vergewaltigung erst zurückzieht und sogar seinen Freundinnen, die selbst Opfer sexueller Gewalt waren, zuerst nichts von seinem Problem erzählen kann.

Coel schafft ein realitätsnahes Bild; man sieht, wie schwer es gerade männlichen Opfern fällt, sich Hilfe zu suchen. Die sehr ernüchternde Erfahrung mit einem unsensiblen Polizisten, als Kwame die Vergewaltigung anzeigen möchte, zeigt auch, wie mit männlichen Opfern umgegangen wird und wie stigmatisiert schwuler Sex noch immer ist.

I May Destroy You verhandelt sexuelle Gewalt auf vielen Ebenen und zeigt dabei, dass die gleiche Straftat unterschiedlich thematisiert wird, je nach race und Gender der Opfer und Täter*innen.

Während Kwames Erfahrung auf der Polizeistation sehr negativ ist, wird mit Arabella als Frau viel sensibler umgegangen. Auch weitere Privilegien werden diskutiert. Etwa als eine Weiße ehemalige Schulkameradin von Arabella gezeigt wird, die eine Selbsthilfegruppe für Opfer sexueller Gewalt leitet, aber zur Schulzeit selbst einem Schwarzen Jungen eine Vergewaltigung unterstellt hat, nachdem dieser ein Sexvideo von ihnen geteilt hatte. Neben der Thematik, dass mit ihr als Weißer Frau anders umgegangen wird, wird hier eine weitere große Frage aufgemacht – wann beginnt Missbrauch?

Das fragt sich auch Arabella, die im weiteren Verlauf der Serie Opfer von Stealthing wird – dem heimlichen Abziehen des Kondoms ohne das Wissen oder die Zustimmung des Sexualpartners während des Geschlechtsverkehrs. Arabella erfährt zufällig beim Hören eines Podcasts, dass Stealthing unter britischen Gesetz eine Form der Vergewaltigung ist und konfrontiert den Täter mit dieser Beschuldigung.

Ihre beste Freundin Terry (Weruche Opia) hat im Italienurlaub einen Dreier, den sie als spontanes und selbstbestimmtes Abenteuer erlebt. Als sie später erfährt, dass die zwei Männer alles vermutlich geplant hatten, fühlt es sich nicht mehr so selbstbestimmt an. Man beginnt sich als Zuschauer*in selbst zu fragen – wo beginnen Übergriffe? Kann der Sex, den Terry mit den Männern hatte, dann überhaupt noch einvernehmlich gewesen sein?

Die Drama-Serie hat jedoch trotz der düsteren Themen auch leichte Momente. Sie zeigt Empowerment, Diversität, Freundschaften und alltägliche Probleme von Millennials, inklusive einer ausufernder Online-Selbstinszenierung, was der Serie noch mehr Authentizität verleiht. Wir sehen, wie Arabella ihre Arbeit aufschiebt, wenn sie pleite ist, Probleme mit der Deadline für ihren Buchdeal hat und wie sie mit Schreibblockaden kämpft.

Mit einem sehr diversen Cast rückt Coel die westafrikanische Diaspora Großbritanniens in den Vordergrund. Durch viele kulturelle Details gelingt eine authentische Darstellung, so etwa durch die Sprache – von Black British Slang, verschiedenen westafrikanischen Akzenten, Twi, das in Arabellas Familie gesprochen wird, bis hin zu Yoruba-Wortfetzen („Oya!“ – „come on!“).

Obwohl auch Weiße Frauen sich mit vielen Themen aus I May Destroy You identifizieren können, bleibt es die komplexe Geschichte einer Schwarzen Frau, was angesichts der Unterrepräsentation Schwarzer Frauen in Medien von großer Bedeutung ist. Wärend viele Serien sich rassistischer Klischees der „Black Mama“, „angry black woman“ etc. bedienen, gelingt Coel eine vielschichtige und überzeugende Darstellung Schwarzer Identitäten. Rassismus wird zwar auch thematisiert, die Schwarzen Protagonist*innen werden jedoch nicht darauf reduziert.

Trotz all des Lobs bedarf es auch kritischer Anmerkungen. Eine Szene ist mir hier deutlich in Erinnerung geblieben: Kwame beschließt nach der erlebten Vergewaltigung, erst einmal Abstand von Männern zu nehmen und schläft mit einer Weißen Frau, welche Schwarze Männer fetischisiert. Als sie nach dem Sex etwas Homophobes äußert, erzählt Kwame, er sei selber schwul, worauf sie ihn wütend auf der Wohnung wirft, sie fühle sich missbraucht von ihm. Kwame ist zuerst verunsichert, dann sichtlich beschämt. Ein Gespräch mit seinen Freundinnen verschlimmert dies noch. Hier gehen die Stimmen der Zuschauerschaft auseinander, hat Kwame die Frau im falschen Glauben gelassen, er wäre heterosexuell, um mit ihr zu schlafen? Sind sie etwa „quitt“, weil er nichts von seiner Queerness erzählte, sie ihn aber auch sichtlich fetischisierte? Ich persönlich konnte die Szene nicht nachvollziehen; warum spielt es eine Rolle, ob sich Kwame als schwul, bi-, pan-, oder heterosexuell versteht, wenn das Paar einvernehmlichen Sex hat? Ich hätte mir hier einen weiteren Blickwinkel gewünscht; der Schock der heterosexuellen Frau, als der eigene Sexpartner sich als queer herausstellt, ist zudem eine gängige homophobe Reaktion. Hätten sie ein anderes Datingverhalten gehabt, bei dem ein ehrliches (romantisches) Interesse von der Frau erkennbar gewesen wäre, dann wäre Kwames Verschweigen seiner eigentlichen Sexualität natürlich von anderem Gewicht. Dennoch, Sexualität ist ein Spektrum und Tendezen können sich auch ändern.

Nichtsdestotrotz ist I May Destroy You eine große Bereicherung der Popkultur, welche zurecht international gefeiert wird. Die diversen Perspektiven, aus welchen die Serien das Thema consent beleuchtet, hat es so in einer TV-Produktion noch nicht gegeben. Der Erfolg von I May Destroy You ist hier sicher auch wichtig, um den Weg für weitere feministische und antirassistische Produktionen zu ebnen.

Über die Autorin:

Elena Schaetz ist Studentin der Afrikawissenschaften (MA) an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Ihre Arbeitsschwerpunkte sind Literatur, Kultur, Gender und Queerness in südafrikanischen Regionen.

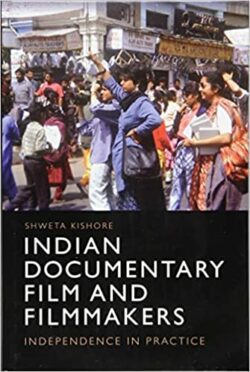

Reviewed by: Nadja-Christina Schneider

Reviewed item:

Shweta Kishore. 2018.

Indian Documentary Film and Filmmakers. Independence in Practice

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

ISBN 9781474433068

The struggles of independent critical filmmakers in India: History going in circles?

In the summer of 2019, when the central government in India denied permission for ‘veteran’ documentary filmmaker Anand Patwardhan’s latest film Vivek (Reason) (2018) to be screened at the renowned International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala, the organizers of the festival, together with Patwardhan, did what he often did when his earlier films faced state censorship. They took the battle to court, won the case, and finally got permission to screen the self-funded and searingly critical documentary at the festival in Thiruvananthapuram. Structured in eight parts, Vivek scrutinizes the mainstreaming of violent Hindutva ideology and majoritarian nationalism in India during the last decade. While the successful litigation in Kerala could be seen as a glimmer of hope for the continued possibility for audiences to engage with critical independent documentaries in India, the fact that Vivek, along with a number of other critically acclaimed films, was not screened at the 16th Mumbai International Film Festival in January this year (MIFF 2020) may not have come as a surprise for many.

Read the full article here: https://www.iias.asia/the-newsletter/article/indian-documentary-film-and-filmmakers

by Jingjing Feng, Pamela Gutierrez and Zuzanna Tarka

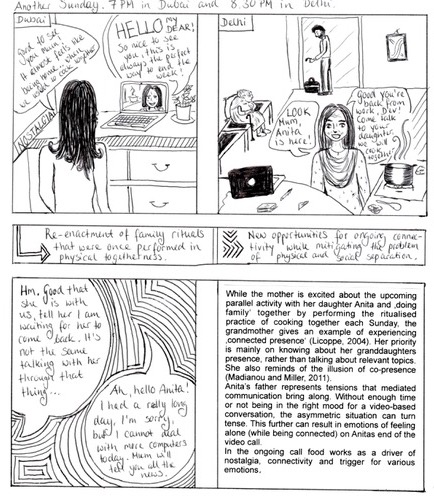

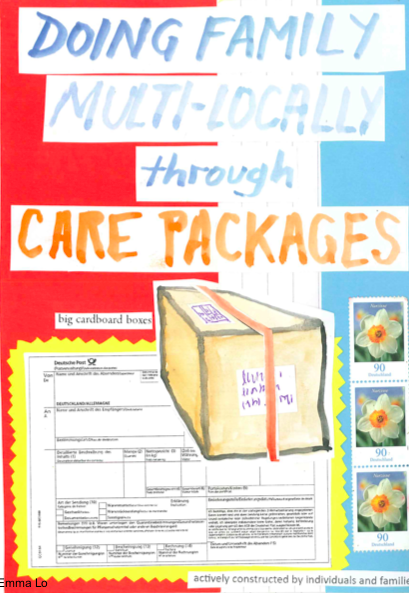

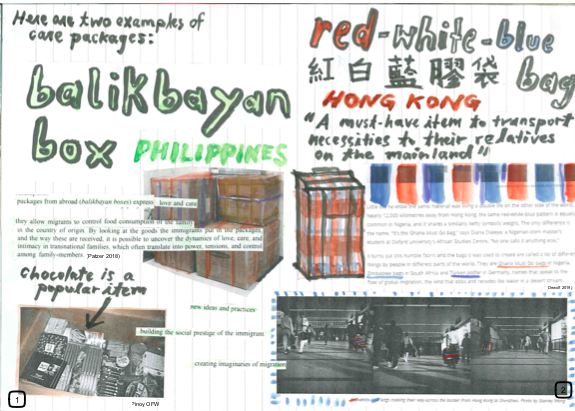

As a third project in the research-oriented MA course „Multi-local families in times of increased geographical and communicative mobility“ (summer term 2020), we present Jingjing Feng’s, Pamela Gutierrez’s and Zuzanna Tarka’s visual essay Comparative analysis of 3 documentaries reflecting on multi-local practices in 3 different cultures.

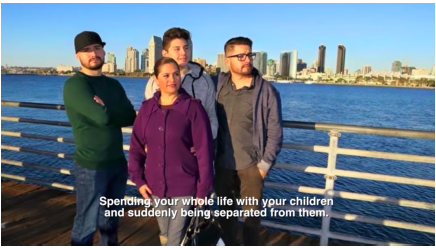

As people across the world people continue to migrate regionally and transnationally, more families find themselves searching for ways to “do family” from a distance. The benefits of migration are plentiful and for many include better financial opportunities and increased safety but often come at a steep cost (Kaur and Shruti, 2016; Faist, 2010). Multi-local families face daily logistical and emotional challenges that transcend nationality and culture despite the unique circumstances across the globe (Schrier, 2016). We chose to explore these cross-cultural challenges by analysing three short documentaries focusing on the countries and regions we identify with—Poland, China, and Latin America/ USA. We looked at “Violetta: Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London”, “Year of the Dog: Inside the World’s Largest Human Migration,” which focuses on a couple migrating from a village in rural China into the city, and “Immigrant Voices of America: Esther Alvarado,” which explores a Mexican woman’s story of migration into the United States. Each offered us a unique perspective into the lives of multi-local families and how they rose to the challenge of “doing family” in circumstances that are quickly becoming more common throughout the world.

- Violetta – Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London (2012)

Still from the documentary film “Violetta – Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London” by Rabikowska, M. & Hawkins, M. (2012).

In this documentary we are shown the life of a Polish women in her mid-forties, an immigrant, who left the country for economic reasons. She has debts to repay back home and knows she can make a better living in the UK. In deciding to do that, her family needs to split – her daughter stays with her ex-husband, while her grown-up son goes with her to the UK to work. Despite having her son and some semblance of family in her new country of residence, the struggles of a multi-local family persist. When she talks about her daughter back home, she says “I miss Natalia terribly, despite everything. She is a girl, and it is different with a boy”. At home she says the two had a good relationship and could talk about anything, but that closeness is difficult to maintain from afar.

The familial dynamic with her son and partner also changed when they moved to London as they traded their family home for a shared, workers household. In the house, several multi-generational families live together under one roof and share common areas, as well as spend their free time together. The importance of family ties evolves for Violetta as she embraces her new community. Eventually they even act as a sort of substitute for her nuclear family as they live together, work together, and even go to church together. As this relationship with her housemates grows, their lives in London and Poland begin to overlap.

Still from the documentary film “Violetta – Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London” by Rabikowska, M. & Hawkins, M. (2012).

On Easter she is seen celebrating with her housemates, phoning home together, and even switching phones to send regards to the other’s family members. Digital media and mobile devices play an important role in their multi-local family practices (Robertson et al., 2016; Schroeder, Ling, 2013). Occasionally, she and her friends and families visit each other back and forth between London and Poland. They all pay a lot of attention to keeping up the traditions, staying in touch with the loved ones who stayed at home and talk about their longing to go back to their country.

Her relationship with the UK is more complex and she experiences both gratitude and acceptance but sometimes also disappointment with life outside of Poland and without her family.

“It is not my second homeland, and I will never call it my homeland” says Violetta, despite living in London for years. Her immigration to London changes her sense of belonging back home in Poland but she doesn’t feel a sense of English identity either. It is touching when she says “After all, human beings are social creatures, and need someone else at all times, to love and to look after… Whether it is children, a husband, or parents, there’s always someone”. This sentiment also reflects in her frequent communication with friends and family back home and her continued longing to be with her daughter again.

2. Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration (2017)

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

In this documentary we are introduced to a couple, Yang and his wife Liu, Chinese domestic migrant workers from a small rural village in China who travel to the big city, Shenzhen, for work. Like Violetta in London, they travel far from their home to secure a better financial future for themselves and for their children back home. Living in Shenzhen allows them to support the family financially and put the children through school but also means the children are left with a grandparent back in their village. Factory workers in Shenzhen can earn up to three times more than they would back in their villages and most of it goes to their family. Yang and Liu send monthly remittances to their village, where Yang’s father is taking care of their two children, a 9-year-old boy and a 15-year-old girl (read more on importance of remittance as currency of care in multi-local family settings in Kaur and Shruti, 2016). Because of the very limited income, they are only able to visit home once a year. Digital technologies such as Wi-Fi and mobile phone signal is limited in their village which is in a very rural secluded part of the country meaning they are not able to communicate regularly with the family left at home. Their situation resembles that of many migrants worldwide, who are limited in the use of digital technologies, and therefore cannot fully benefit from the possibilities it gives to multi-local families to stay connected (Kaur and Shruti, 2016). Instead, they make one costly trip home a year to celebrate the Chinese New Year in which they try to make the most of the time they spend with family.

Before leaving Shenzhen, they go to a market to buy all sorts of gifts: nuts, sausages, snacks, new clothes – things they hardly buy for themselves on a regular day working in the city. This reflects the lives of millions of rural migrant workers in China who work hard to make the most possible money but never spend on themselves (Cai, 2003) The high cost of living and legal situation prevents them from taking the children with them to the city and the long distance puts a strain on the relationship with their young children who find it hard to reconnect with the parents after a their long absences.

To get home Yang and Liu must endure a more than 30-hour train ride in which they are lucky to even get a seat. When they finally arrive home, they are tired but excited to reunite with their family. Their 9-year-old son has been waiting anxiously to greet them from afar, but the 15-year-old daughter is less enthusiastic and doesn’t want to come out from her room. The fact that she did not grow up with her parents, let alone to build an intimate relationship with them, leaves her with a complex mix of emotions and ambiguous feelings about her parents’ return. On the one hand, she is happy that she finally sees her parents and understands that they go away to make a better life for the family, but also likely blames them for not giving her the kind of emotional love and intimacy that she has needed. Liu, her mother, is understanding. “We haven’t been there for her growing up. That is our loss”.

The left-behind children of Chinese rural migrant workers have become a hot topic for debate in recent years. Left-behind children living apart from their parents is a striking example of the changes emerging in China’s traditional family structure in the midst of economic development (Liu et al., 2000). Studies have shown that left-behind children are particularly vulnerable to exposure, to trauma and neglect and are at greater risk of developing depression (He. B et al. 2012).

3. Immigrant voices of America: Episode 1 – Esther Alvarado (2020)

Still from the documentary film “Immigrant voices of America: Episode 1 – Esther Alvarado” by Duran, M (2020), A Start Now Studio.

The documentary tells the story of a Mexican woman, Esther, who is forced to live away from her family in the United States while her American immigration status is deliberated. Esther Alvarez, the matriarch of the family, has similar motivations for beginning the long and arduous journey into the United States as the Yang, Liu and Violetta had for their own migrations. Much like the Yang and his wife Liu, Esther’s goal was to provide for her children and “…take advantage of all the opportunities this country [the USA] provides that unfortunately we don’t have in our country.” Esther also shares in Violetta’s motherly grief, both women lamenting the long separation from their families. However, unlike the others who migrated domestically or within the then European Union, she is faced with administrative uncertainties regarding her legal status in the United States that barres her from reuniting with her family, all of which have made the US their new homeland and are anxious to welcome her back.

While separated from her family she engages in practices of “connected presence” Robertson et al., 2016, p.219) using any means to keep in touch with her loved ones: following the lives of her children and grandchildren online, watching videos and photos of them growing up, keeping in touch through phone calls, and receiving visits from her kids while she can’t enter the country. When she was forced to separate with her family for the second time, she said “it was like cutting off the wings off a bird, one second, it’s flying around an all of a sudden someone cuts off its wings.” Esther was separated from her family for seven years from 2007 to 2014. She goes through a long and humiliating process of applying for legal entry to the country despite already having lived there for many years, being married to a US resident, and having no criminal record. Her son, a Youtuber, organizes a campaign pushing for her case to be reviewed in an effort to help his mother and all families separated by harsh immigration laws. After seven years, two failed attempts and two months in an ICE detention centre she is finally granted entry to the country and reunited with her family. (Read more about ICE and why it is controversial: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/us/politics/fact-check-ice-immigration-abolish.html)

Esther endured many hardships throughout her life from being a teenage mother, to experiencing sexual assault by a smuggler during her first attempt to cross the border at 19, later getting deported, detained, and fighting for her right to a life in her adopted home. Though it all she says, “the love that I have for my children, the hope of returning to them, to be with my granddaughters, that’s what kept me going.” On February 5, 2019, Esther finally attained her U.S. Residency and she did not have to worry about being separated with her family again. It took 32 years.

Multi-local Families and Migration Across the World

Still from the documentary film “Immigrant voices of America: Episode 1 – Esther Alvarado” by Duran, M (2020), A Start Now Studio.

All the documentaries which we have seen are stories of people, who are struggling to improve their lives, while living away from their families for extended periods of time. All are recent stories and present us with the most common forms of migration in different parts of the world – Polish workers living in the UK and sending money home, Chinese families migrating from rural areas to cities while their children remain with their grandparents, and Mexican-American families being forcibly split by the immigration laws. Although we see very different life situations, reasons for their separation, and cultural background, each story connects to one another through the common themes of separation, familial bond and practices adopted to stay in touch with the loved ones at a distance.

The foundation of the multi-local family appears to be fundamentally the same across the world. Everyone hopes to live safely, to have the opportunity to prosper, and most importantly to experience the love and care of a family. Even with these similarities, families engage in unique struggles across the world. In the cases on Violetta, Yang and Liu, and Esther, they all left their homes in search of financial opportunities and to provide for their families. In Mexico and across Latin America, this motivation is sometimes followed by a need for safety, as certain areas are plagued with gang or political violence that can make migration literally a matter of life or death. Unfortunately for many, this danger is not politically recognized by those in power. For many immigrants to the United States, separation comes in pairs; first from their country of origin and later from their families and the life they’ve built in the US over many years. Deportation is a real and looming threat as immigration policy has become stricter in recent years and even those seeking asylum aren’t immediately safe from the federal enforcement agencies such as ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) or Customs and Border Protection. Multi-local families are made by literal force, not just by choice, and the ramifications are felt through multiple generations as was the case for Esther, her sons, and her granddaughters and contribute to patterns of circular migration (Hagan, J., Eschbach, K., & Rodriguez, N., 2008).

the journey home.

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

For all migrants, regardless of situation, the journey comes with a price. For Violetta this means leaving not only her family but also her native land, culture and language for a different country, devoid of the comfort and familiarity of home. She worries for her daughter and also for her country, at one point in the documentary anxiously discussing the enormous snowfall in Szczecin that knocked out electricity to the city. To paraphrase the English expression, “You can take the woman out the country, but you cannot take [Poland] out of the woman.” Our history, like our families, are a part of us all and no amount of distance can erase the love of either in Violetta’s heart and mind.

For Yang and Liu who migrate within their native China, the struggles are equal but different. They don’t need to practice a new language and can enjoy some same of the same cultural norms but are challenged by sheer size of China itself. They must travel thousands of miles to see their family by train, approximately one day and two nights, and have young children that are growing up without them. The village is small and remote and many of the digital technologies that Violetta and Esther rely on to maintain relationships with their distant families are limited or unavailable to the couple. They may remain in China but are perhaps the most cut off from their family while away working in the city.

Esther’s story, though rife with struggle, has almost the opposite problem as Yang and Liu. While in Mexico she lives just across the border from San Diego where her family lives and her son is a Youtuber adept at sharing his life with her digitally. Her close proximity to the United States both affords her visits from her sons who can cross the border into Mexico to see her but also serves to constantly taunt her with what she cannot have. She is at all times, “so close, yet so far.”

In all three documentaries there is the question of expectation versus reality for the families. Violetta has moments of both peace and conflict with her situation in London at one point frustratedly saying, “This is not how I expected it to be. This is not how it should be. I ended up in England doing a shitty job in a shitty factory…”. Multi-local families make difficult decisions when choosing to separate but the result is nearly always a gamble of sorts. Violetta comes back later in the documentary to say that her life is ultimately good in London and she doesn’t wish to immediately go back to Poland but adds, “You cannot rewind time, unfortunately. It always comes with a price.”

Liu faces similar questions when she returns to her village in China and finds that her teenage daughter is not as welcoming as she would have hoped. She briefly wonders if given the choice again she would choose to leave the village. Despite her concerns, her husband Yang knows that village life cannot provide the family with what it needs to survive. He understands that this cycle of migration will continue with his children as there is no opportunity for them at home. Perhaps one of their largest challenges is that their multi-locality as a family is likely to be permanent as the children will eventually replace their parents as migrants to the big city. Yang hopes to return to the village in his old age but by that time his children will be the ones who’ve left home in search of opportunity.

means “confidence.”

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

Violetta and her housemate, despite being comfortable in London, also dream of returning to Poland at some point. On New Year’s they gather for drinks and toast to Poland saying, “To Poland! May we go back someday when it is better.” This is perhaps one of the most striking differences between Violetta, Yang and Liu, and Esther. For Esther from Mexico, her story of migration is meant to be permanent. Her children have been raised in the US and are now raising their own children in the country. Mexico will always be a part of their family story, but their lives are now in San Diego making her separation all the more unbearable. Of migrating to the US, she says, “My objective was always to become a U.S. citizen and to continue contributing to this country, to work, excel, and give a better future to my son[s]…”

In all documentaries we see families split for long periods of time and big distances because of necessity. Whether for the economic or legal reasons, these times of absence become an important factor for how they build and sustain relationships with their kin and loved ones. Especially for parents separated from children, they face many difficulties in maintaining the high level of emotional involvement in each other’s lives (Schrier, 2016). In order to make it possible they engage in variety of different practices of connected presence (Robertson et al., 2016; Licoppe, C., 2004) – sending money home, visiting family when possible and bringing gifts for the family members (Kaur and Shruti, 2016), celebrating traditions, foods and national holidays together, as well as keeping in touch through social media, phone calls and sharing photographs (Robertson et al., 2016). People who are forced to leave their family homes and family members behind to improve their quality of life often still question their decision to leave and become melancholic when considering the possibility of going back to their homelands even while knowing that’s not possible. While taking advantage of the “the possibilities of simultaneity” (Huang et al. 2008 , p. 7), the forced separation from the families seem to be increasing the internal divide of being “neither here, nor there” (Huang et al. 2008 , p. 7).

Still from the documentary film “Year of The Dog: Inside The World’s Largest Human Migration” by Vice (2017).

Analysing multi-locality through documentaries

In addition to presenting different kinds of migration stories, the documentaries themselves use different formats to deliver their messages. The artistic form of expression chosen by the authors and creators of the documentaries can tell us a lot about way they approach the topic, their perspective and the topic itself.

“Violetta: Portrait of a Polish Immigrant in London” uses a mix of observational and interview formats to tell her story. It’s the most unfiltered of the three documentaries using a fly-on-the-wall tactic through much of the filming which is later interspersed with interviews with Violetta to contextualize her situation. The title of the documentary itself – ‘a portrait’ – points out to the focus of the director on the figure of the woman, painting an intimate picture of her life, rather than focusing primarily on the aspect of immigration. Because the documentary provides little to no context of the situation in Poland or why London is a popular migration destination, Violetta is allowed to shine as the sole subject of her story. This is positive in that the viewer is allowed to concentrate on her situation as a person, not only under the term “migrant” that often carries its own associations. On the other hand, Violetta is a migrant and contextualizing her story as part of a general narrative of migration from Poland could serve to better understand the situation as a whole. Because of that we get the feeling that Violetta might have been filmed by someone close to her, who understands her life choices well and sympathises with her situation.

The second documentary produced by the big international broadcaster Vice News seems to be done from a very different angle and created with an aim to introduce the realities of the protagonists to the unfamiliar audiences. In what follows, parts of the interview, particularly with the young boy, do not feel natural to a native Chinese speaker who understands the culture. It seems that he is encouraged to answer interview questions in a “correct” way as if he is guided, which reflects another drawback of documentary films in that they always come with some subjectivity of the film maker or the interviewer. Because of this approach we feel the distance from Liu, Yang and their children, and observe their life unfolding like a movie, rather than being pushed by the director to feel how the life in their shoes might feel like. However, in being much more structured than the first documentary, ‘The Year of the Dog” gives a much better background and the overview of the situation, and presents the surrounding in the way that they become the part of the story, and we get to see the link between the protagonists and their changing environments.

Our final documentary, “Immigrant Voices of America: Esther Alvarado,” is one of an eight-part documentary series focusing on the different immigrant groups in the United States and their stories. In this way, Esther’s story is woven into a larger narrative about the immigrant experience in the United States and the various struggles they may encounter. Much like the other documentaries we watched, there is combination of observational and expository techniques as the story of Esther’s life is juxtaposed with images on the screen. However, unlike the previous two documentaries, both Esther and the filmmakers appear to be passing a value judgement on current immigration policies. The viewer is meant to finish the film with a new sense of right and wrong, having been more than just educated on her story but also the political undertones of her situation. Depending on the topic and each person’s set of values, this can be either positive or negative as the filmmakers are aiming to convince the viewer of one position over another. In addition to the filmmakers, Esther’s eldest son is a prominent Youtuber and films some of the more intimate footage himself including scenes at the hospital when Esther is undergoing cancer treatment. This close personal connection to the subject is beneficial in that the viewer feels a true sense of consent as they follow her on this very personal journey. Also because of her son’s YouTube career, the documentary incorporates previously shot footage from his channel and allows us a glimpse at Ether’s story over many years. Again, this makes for an intimate but not impartial view of Ether’s life as an immigrant, a stark contrast to Violetta, Yang and Liu’s films which primarily aim to tell as story and allow the viewer to judge or interpret their stories for themselves.