This research-oriented interdisciplinary seminar sought to critically examine historical as well as current perceptions and discourses about academics who, due to institutional, structural or political constraints, were forced to leave their home country and seek exile elsewhere. In contrast to well-known artists or authors, exiled academics are often at the margin of inquiries into their specific situation and self-positioning. The seminar therefore aimed at a deeper understanding of their specific situation and self-representation. Students formed three research teams and carried out their own empirical research explorations into these topics. They were advised by teacher tandems and had the opportunity to specialize in one of three focus areas:

Focus area 1: Academics and identities on the move? The role of (social) media in processes of identity construction (Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Özen Odağ, Touro College Berlin, and Dr. Olga Hünler, Universität Bremen)

Focus area 2: (Transnational) Networks in Exile – Topics, Discourses and Advocacy (Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Carola Richter, Freie Universität Berlin, and Dr. Amal El-Obeidi, Universität Bayreuth)

Focus area 3: Cities of academic exile and their translocal networks (Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Nadja-Christina Schneider, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Prof. Dr. Nil Mutluer, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin)

Summary of Focus Area 1: Goals, research questions, and empirical studies

Participants:

Prof. Dr. Özen Odağ, Dr. Olga Selin Hünler (Supervisors)

Serra Bozdoğan, Klara Ronzheimer & Emma Tordoff (Students of Touro College Berlin)

Summary:

Focus area 1 explored the identity work that exile academics engage in and thus represented a psychological perspective of academics on the move.

Research Questions:

- How are exile academics represented in their home country (in terms of ascribed identities)?

- How do exile academics construct their identity in their new environment and adapt?

Our focus was on Barış için Akademisyenler (BAK) – Academics for Peace (see a detailed description of this group below).

Our research questions were addressed in three separate empirical studies.

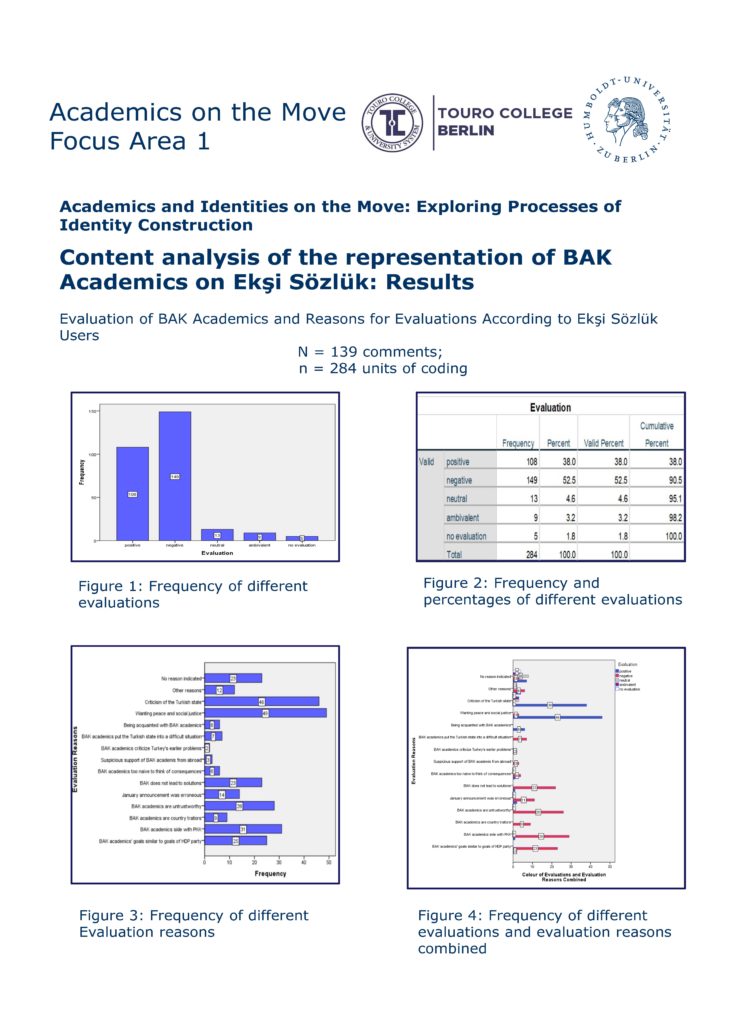

Study one content analysed the representation of BAK Academics on Ekşi Sözlük, an alternative social media platform used by the general public in Turkey to express public opinion and discuss a large variety of socio-political trends in and outside of Turkey. The platform is the largest online community in Turkey, currently hosting more than 400.000 registered users.

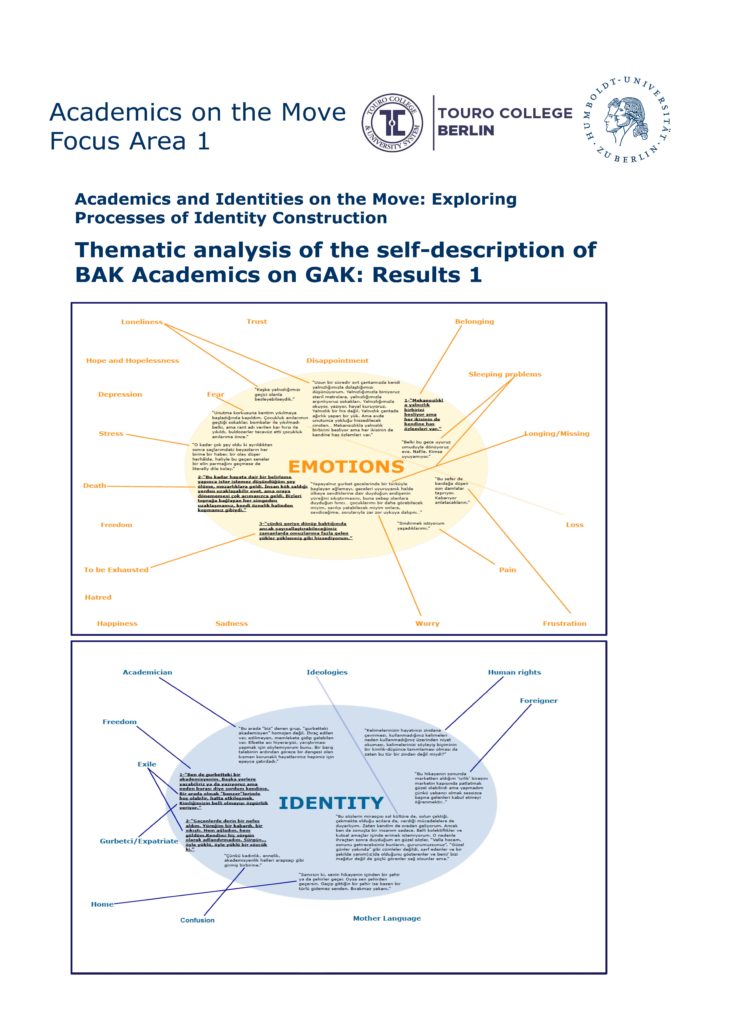

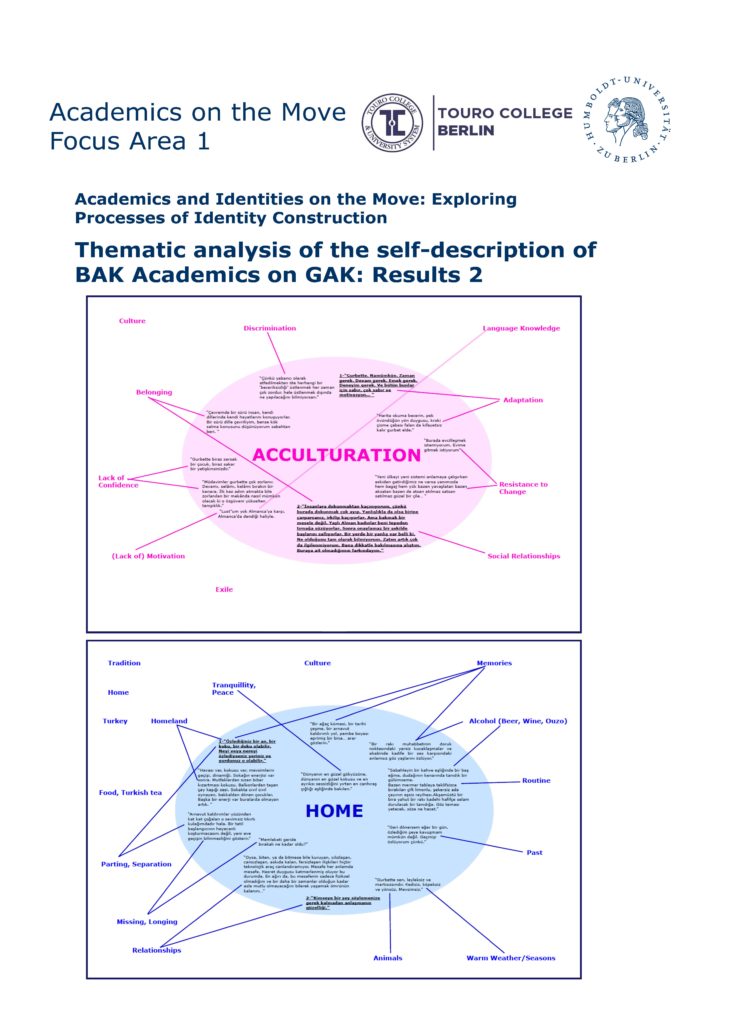

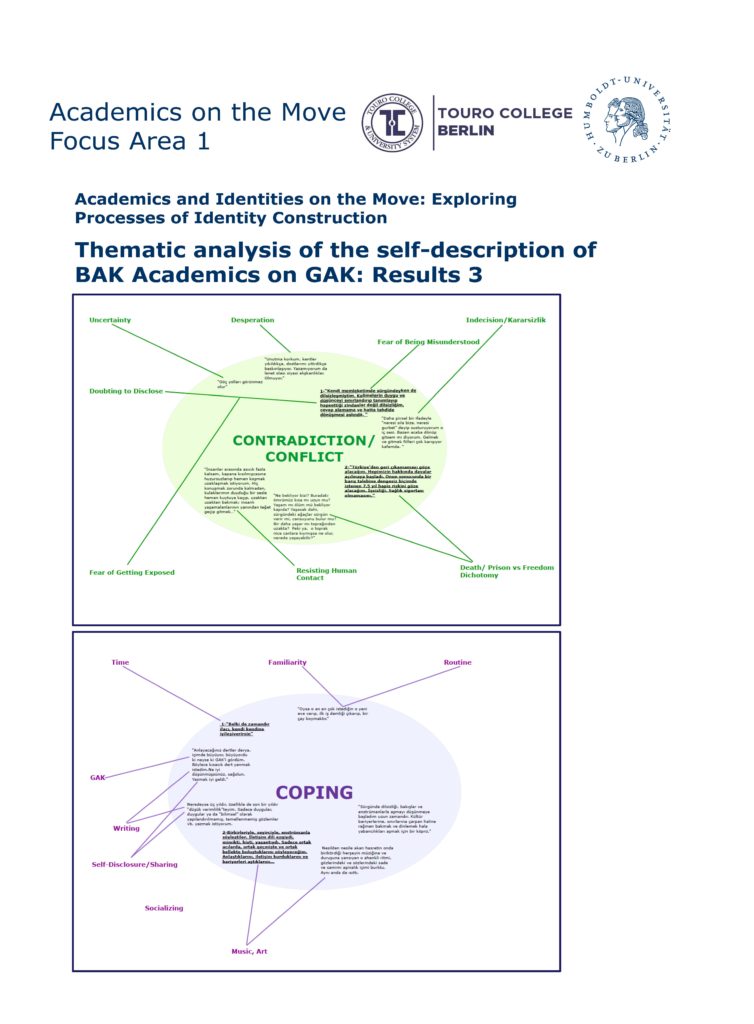

Study two was a thematic analysis of the self-description of BAK-Academics on the BAK-Academics blog Gurbetteki Akademisyenler (GAK – Academics in the Foreign Land). This blog is used by Turkish academics in exile as an autobiographic space for self-expression. Blog entries touch on topics as various as identity, personal struggles, home, coping strategies, and emotions.

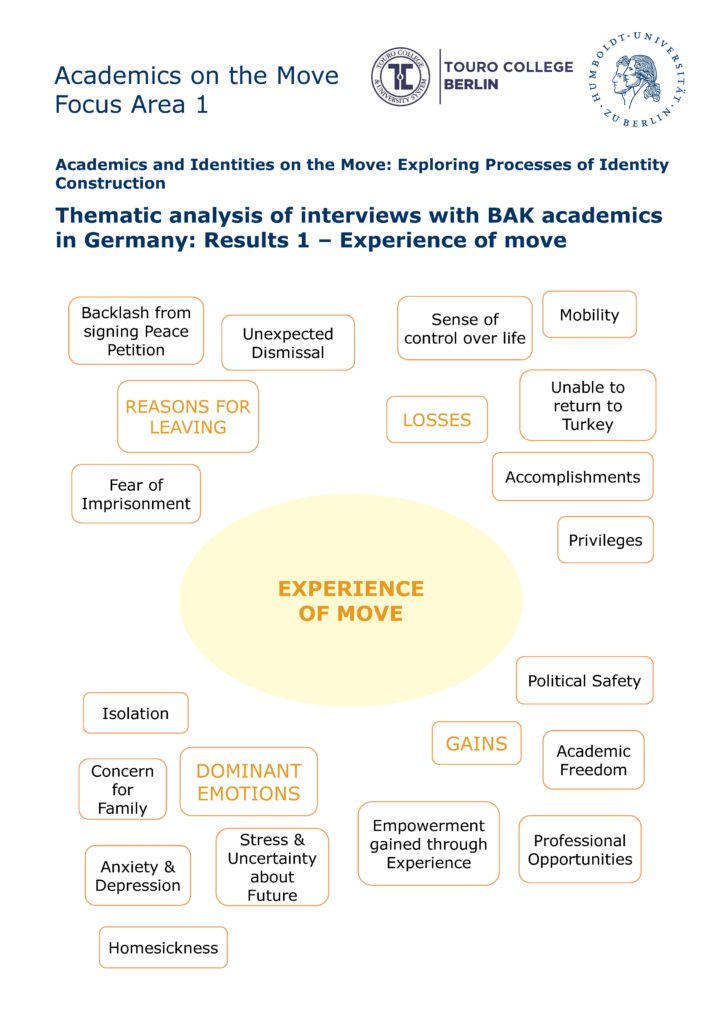

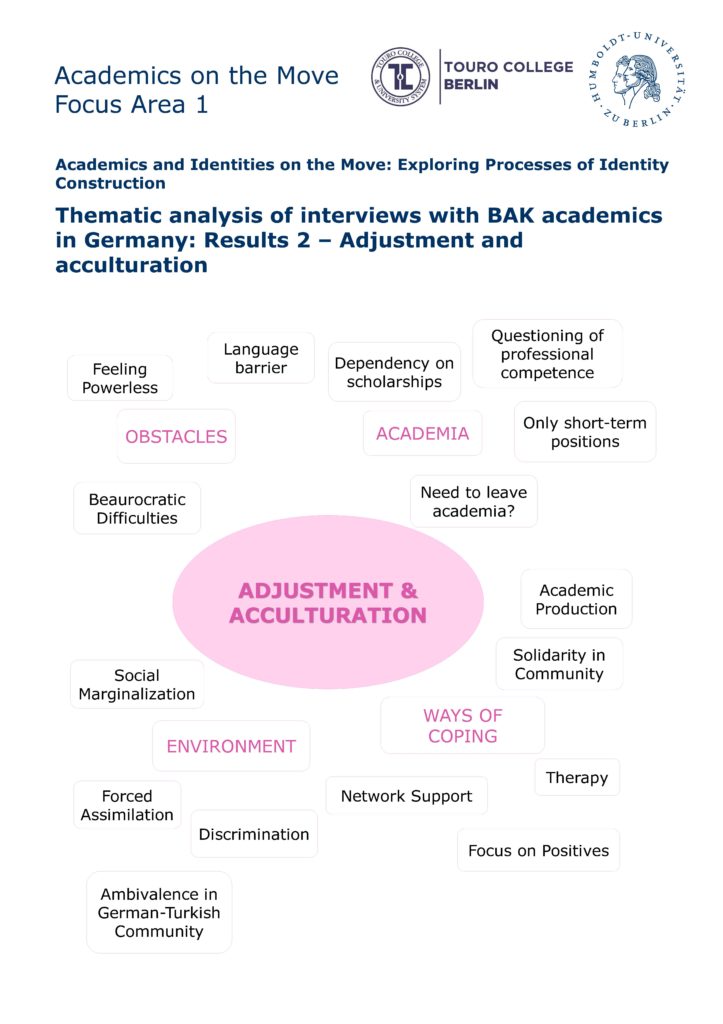

In Study 3 we interviewed five BAK academics currently residing in Germany with respect to their identity and adaptation in Germany (see interview guide below).

Our research design, questions, and specific studies including results are presented on separate posters assembled in Power-Point-Slides available for viewing in this blog:

Our theoretical background, research design, and specific studies are described in more detail on our PPT 1: Research design.

The results of Study 1 and Study 2 are presented in more detail on PPT 2: Social Media Analysis.

The results of our interview study (study 3) are presented in more detail on PPT 3: Interview Results.

Background info on ACADEMICS FOR PEACE – BARIŞ İÇİN AKADEMİSYENLER

Academics for Peace (AfP)[1] are the signatories of the petition “We will not be a party to this crime!” which was publicized in January 2016. The peace petition was condemning the Turkish government’s military operations in the mainly Kurdish populated Southeastern cities of Turkey, because of the tragic impacts on the civilians and calling for an end to violence in the region.

Since the declaration of the petition, AfP faced numerous violations. Hundreds of the signatories were fired from their jobs or forced to resign or retire, they were removed and banned from public service with the decree laws, their passports have been cancelled, several were physically and verbally threatened, and four of them were imprisoned. The AfP are facing the penal proceedings in assize courts with the accusation of “Making Propaganda for a Terrorist Organisation” based on the Article 7/2 of the Turkish Anti-Terror Act and the Article 53 of the Turkish Penal Code.

Despite all defamations, threats and harassment, AfP manage to resist to repressions and collectively support each other. AfP have received several letters of support from international academic organizations, including MENSA, APA, IAFFE, ASA as well as messages of solidarity from internationally recognized academics, including Eric Fassin, Steven Pinker, Noam Chomsky, Judith Butler and many more.

AfP received the 2018 Courage to Think Defender Award, for their extraordinary efforts in building academic solidarity and in promoting the principles of academic freedom, freedom of inquiry, and the peaceful exchange of ideas. AfP were also awarded with the Aachen Peace Prize, the Academic Freedom Award of the Middle East Studies Association of North America, as well as the 8. Johann-Philipp-Palm-Preis, and some more.

The signatories of the peace petition reside in different geographies, they teach, conduct research, publish their work, but also continue to spread the message of a peaceful resolution of conflicts. They promote the ideas of academic freedom and the values of university world-wide and strive to support each other by all means.

Academics for Peace Germany (AfP-Germany)[2]

The association was founded in Germany on October

2017 by the signatory academics and the colleagues who supported the values of

academic freedom and freedom of speech. AfP-Germany organizes campaigns for the

solidarity with peace academics and raises awareness and support with

colleagues who have been threatened, targeted, lost their job, and banned from

working in public service. Our aim is to function as an international “hub” for

human rights organizations, NGOs, academics, as well as international press

seeking information on the repression against Academics for Peace in Turkey.

TOPICS and INTERVIEW GUIDE – STUDY 3

- Topic 1: Experience

O’Keeffe,P., Pásztor, Z. (2016). Syrian Academics in Exile, in New Research Voices

Pierigh, F (2017) Changing the Narrative: Media Representation of Refugees and Migrants in Europe, published by World Association for Christian Communication – Europe Region

- Topic 2: Acculturation & Adaptation

Mesquita, B., Leersnyder, J., & Jasini, A. (2017). The Cultural Psychology of Acculturation, in The Handbook of Cultural Psychology

Liebkind, K. (2006). Ethnic identity and acculturation. In The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology

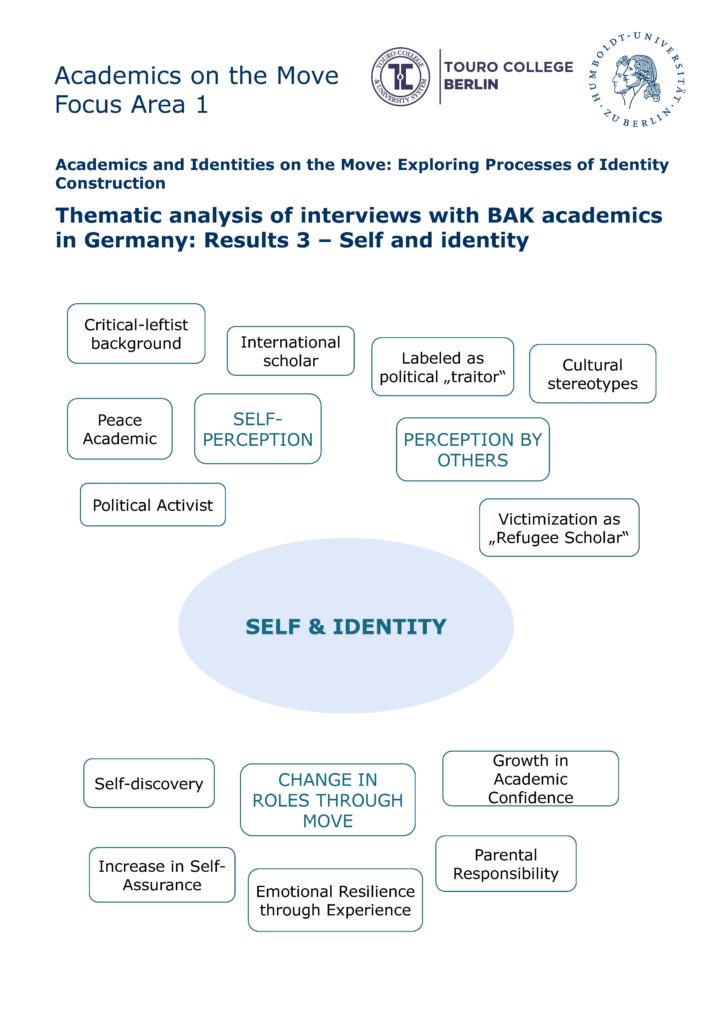

- Topic 3: Self & Identity

Vignoles, V., Schwartz, S. & Luyckx, K. (2011) Towards an Integrative View of Identity, in Handbook of Identity Theory and Research

Bhugra, D.,

& Becker, M. A. (2005). Migration,

cultural bereavement and cultural identity. World psychiatry : official

journal of the World Psychiatric Association

For the detailed interview guide, please click here.

[1] https://barisicinakademisyenler.net/node/314

[2] https://academicsforpeace-germany.org/

Academics and Identities on the Move: Exploring Processes of Identity Construction – Research Design

Academics and Identities on the Move: Exploring Processes of Identity Construction – Social Media Analysis

Academics and Identities on the Move: Exploring Processes of Identity Construction – Analysis of Interviews

This research-oriented interdisciplinary seminar sought to critically examine historical as well as current perceptions and discourses about academics who, due to institutional, structural or political constraints, were forced to leave their home country and seek exile elsewhere. In contrast to well-known artists or authors, exiled academics are often at the margin of inquiries into their specific situation and self-positioning. The seminar therefore aimed at a deeper understanding of their specific situation and self-representation. Students formed three research teams and carried out their own empirical research explorations into these topics. They were advised by teacher tandems and had the opportunity to specialize in one of three focus areas:

Focus area 1: Academics and identities on the move? The role of (social) media in processes of identity construction (Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Özen Odağ, Touro College Berlin, and Dr. Olga Hünler, Universität Bremen)

Focus area 2: (Transnational) Networks in Exile – Topics, Discourses and Advocacy (Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Carola Richter, Freie Universität Berlin, and Dr. Amal El-Obeidi, Universität Bayreuth)

Focus area 3: Cities of academic exile and their translocal networks (Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Nadja-Christina Schneider, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Prof. Dr. Nil Mutluer, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin)

Focus Area 3

Musealizing Exile: Memory-making, Narration and Epistemological Order in Museums on Exile History

As a participant in the research seminar “Academics on the Move: Notions of Exile, Re-Migration and Translocal Solidarity” I decided to conduct research on musealization practices of exile and of exiles in Berlin. I want to understand how institutions conceptualize and engage with exile. The projects rests on especially two assumptions: museums and archives have an important influence on the extent of a society´s historic awareness because they have to select what they add to their archival holdings or what they decide to display. On the other hand, they might also be influenced by political issues and public debates, for example by receiving project-based funding or by demands for different stories to display. It is, however then, up to the institutions and individuals how aware they are of their responsibilities. Therefore, my aim is not to conduct research on historic exile. Instead, I aim at an understanding in second observation of representational practices. I ask how knowledge on exile is constructed in museums and which phenomena, historical and current, are labelled as exile. I am especially interested whether institutions share a common approach or even a common concept in order to present a history of exile that is more complete.

I decided to approach the topic by conducting conversations with representatives of different institutions which deal with current or historic forms of exile. The choice of institutions ranges from museums, i.e. the Jewish Museum Berlin, to foundations like the Stiftung Exilmuseum to scholarship foundations like the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung which awards the Philipp Schwartz-Scholarship to selected threatened foreign researchers. I chose to talk to institutions of various organizational structure and purpose because each of them engages with the topic and, therefore, has presumably a concept on how to define exile; and, more interesting even, who is not counted as exile. Furthermore, the discussion with the foundation helps me to understand what is perceived as a defining factor of academic exile. The methodology for the research is, thus, mainly based on conversations with exiles while also partially drawing from visual anthropology.

Some preliminary findings were presented at a multimedia exhibition in Touro College in December 2018. The poster at the exhibition focused mainly on two questions: Which space is devised to exiles and exilic history in museums in Berlin? Which gaps and silences are produced within exilic history?

My engagement with the topic since December lead to some new questions and establishment of contact with new institutions. Through the prolonged engagement I became more aware of existing cooperation and collaborations between institutions. My research focus has, however, slightly shifted after conducting several conversations. Instead of only criticizing a gap of awareness in exilic history (mainly, the time between 1950 to 2016), I look at current representations in exhibitions. This means that I observe in exhibitions and in the conversations in which roles exiles are perceived. Are exiles framed as victims? Are current exiles displayed but with the images of historic exiles in head? Does the display rely on a specific knowledge of the visitors? How do museums choose exemplary persons through whose biography they attempt to tell a history of exile? The research project has continuously been gripping for me. It is an interesting experience to learn more about the institutional frameworks and self-critical reflections on current museal practices.

Cities of Academic Exile and Their Translocal Networks